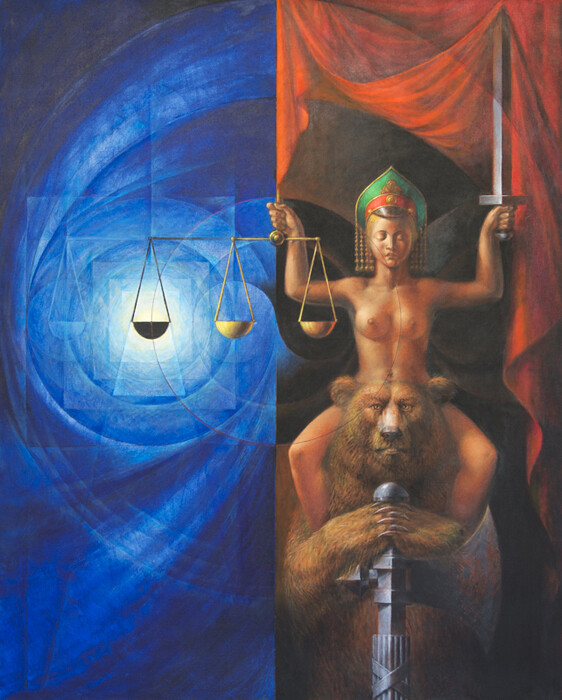

Vitaly Komar, formerly half of the illustrious team Komar & Melamid, which split in 2003, continues to paint in a style he has dubbed “New Symbolism.” For more than a decade, his virtuosic paintings of the proverbial scales of justice, tiny birds of truth, hulking Russian bears waving red flags, and circular serpents biting their own tails have been going through their allegorical paces, wrapping religion in history and spirituality in cosmic swirls. Melamid, meanwhile, has kept a lower profile.

Komar’s recent exhibition at New York’s Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, “Allegories of Justice,” which includes a few earlier works by the former team, raises a number of questions. What happens when an artist duo splits up, as Komar & Melamid did? What happens when the context of any artist’s production—in this case conceptual sociopolitical work satirically skewering both Soviet ideology and American consumerism—vanishes into thin air, as the Soviet system did, leaving them and other Soviet artists without a framework? And how do they continue to make art in the context of the internal void of a suddenly collapsed culture? Also, in the case of Komar & Melamid—who left Moscow in 1977 and moved to New York the next year—how was their work affected by the external disruptions of emigration to a diametrically opposite society?

Komar & Melamid were among the Soviet Union’s best nonconformist artists: they founded “Sots Art”—a merger of Socialist Realism, politicized Pop, and Conceptual art—and called their first joint show back in 1967 “Retrospectivism.” In 1974, they were arrested during an outdoor exhibition in Moscow that has come to be known as “The Bulldozer Exhibition,” because the government used bulldozers to destroy the artworks.1 Their first US show, in 1976 at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, consisted of smuggled works.

As emigrés, they expanded their conceptual critiques—establishing a corporation to buy and sell human souls (Warhol donated his), and making allegorical portraits of Reagan and self-portraits as Lenin and Stalin. They had scientific polls taken in 11 countries of the “most wanted” and “least wanted” paintings for their series “People’s Choice” (1994–97), and produced those banal paintings, only to conclude that “looking for freedom, we found slavery.” For a project titled Ecollaboration (1995–99), they went to Thailand to teach elephants to paint; paintings by Renee, the elephant-painter, auctioned by Christie’s, helped save other endangered Thai elephants. Their final joint project, a series of paintings titled “Symbols of the Big Bang” (2001–2003), involved abstraction, spirituality, and cosmic dualities, pointing the way, as it were, to Komar’s recent work.

Among the symbolic replays and elaborations of scales, swords, and bears brandishing red flags in “Allegories of Justice” is one intriguing, atypical canvas: Pushkin’s Cat (2010–15). It pictures the expanse of an indigo-blue night sky with a central starburst and an indistinct whirlwind of green lettering. Down near the lower edge, an unsmiling cat on a chain peers out at the world. This wise cat is the storytelling narrator of a long epic poem by Alexander Pushkin, “Ruslan and Ludmilla,” a Russian classic dating from 1817. In the poem, the cat—bound by a golden chain “to a green oak by the sea”—walks slowly round and round the tree while retelling ancient Russian folktales and legends, and dreaming sadly of better days gone by. Pushkin’s Cat sums up the mood of Komar’s recent work. The familiar symbols and allegories seemed to have grown distant, generic, and nostalgic. Could it be that the artist, like Pushkin’s cat, is chained to his own painterly past?

According to Komar’s 2009 description of New Symbolism, symbolic allegories may well be “conceptual signifiers that coexist seamlessly with painting’s reverie.” They can arguably be interpreted, as the press release suggests, as a “reflection on the current international political situation.” Or could it be that what’s lacking in Komar’s recent work is the biting satire and critique in the work of the former team? It has become apparent that while Komar may be the better painter, it is very likely that Melamid is the more conceptual and skeptical artist. If only they could bury whatever hatchet caused their breakup and join together for one last body of work to aggressively confront the current economic and sociopolitical situation in Putin’s weird post-Soviet Russia and in a chaotic post-Bush world of failed states, degraded environments, and hyper-capitalism gone berserk.

Beyond the ideologies of production and consumption, past a century in which two former superpowers needed each other for balance, our geopolitical urgencies and planetary anxieties are now unilateral. Together Komar and Melamid might find a way for their art to reflect on our global Sixth Extinction and the environment in the epoch of the Anthropocene. That’s a tall order but if anyone can tackle it, together they might. Their swirling painterly flourishes and acerbic critiques, leavened by a dose of cynicism, would at the very least provide a glorious cap to their career.

“The Bulldozer Exhibition” of September 15, 1974, an illegal exhibition, apparently had no other recorded name. It took place in the Belyaevo area of Moscow.