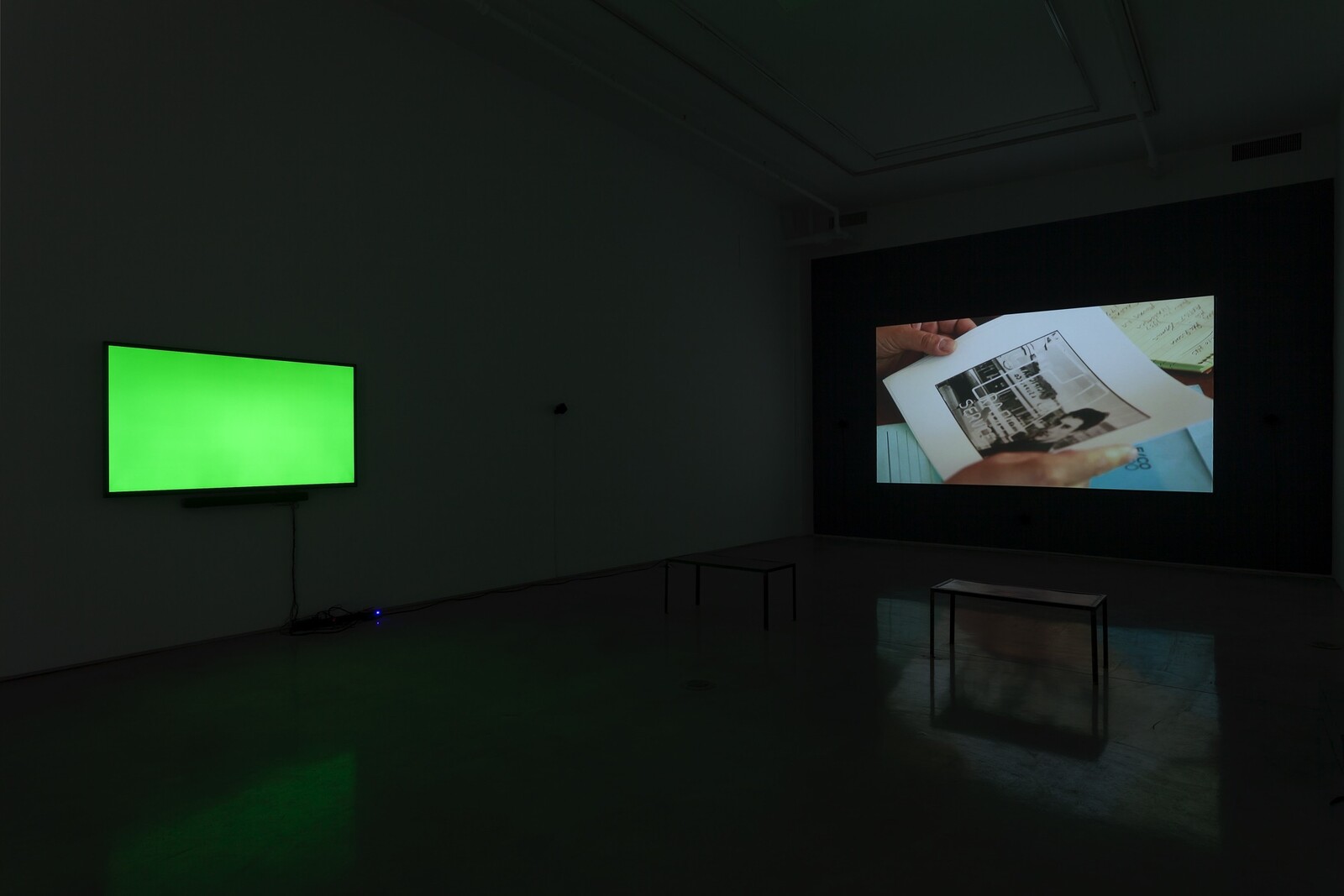

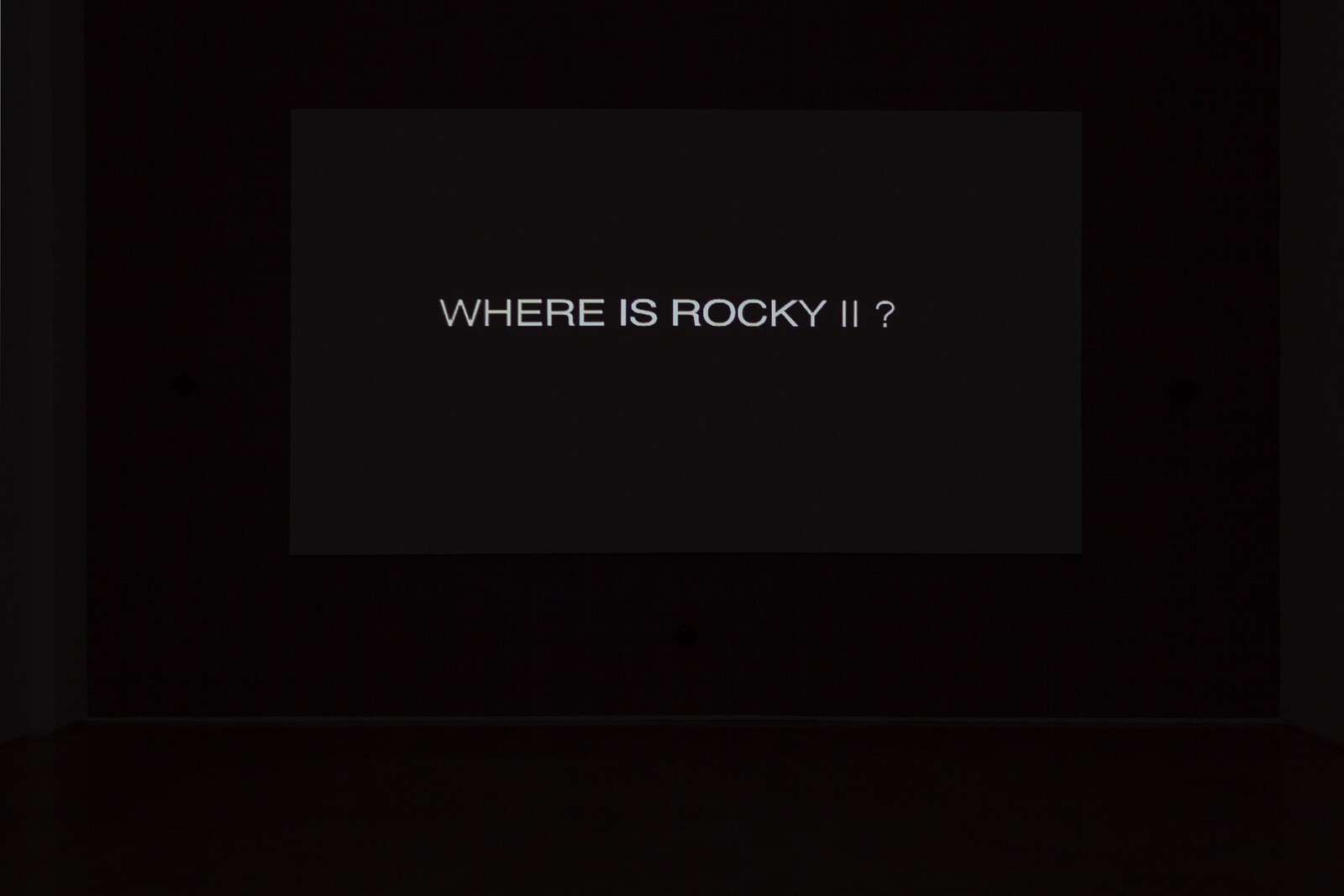

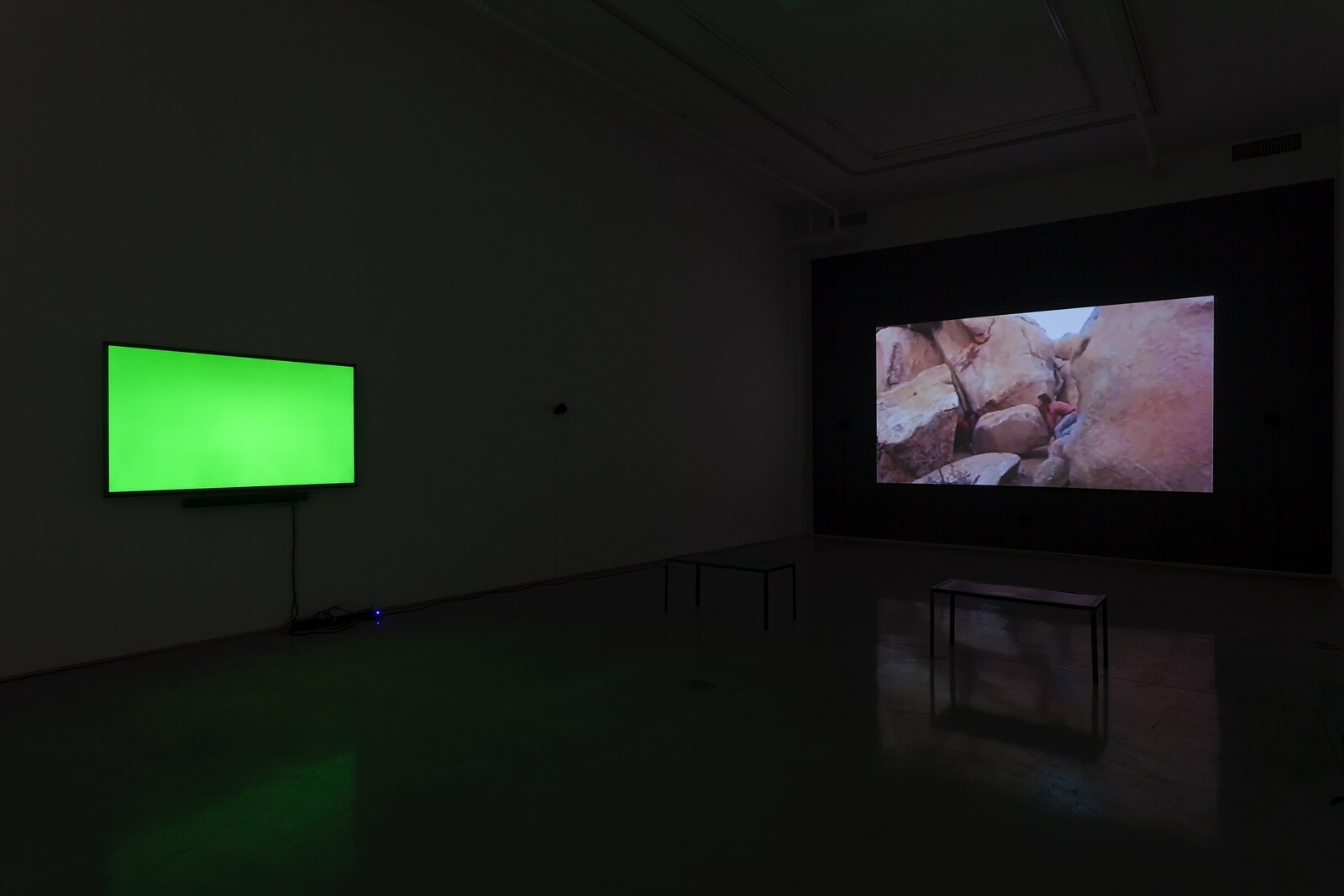

Pierre Bismuth’s “Where Is Rocky II? Teaser-Trailer” offers itself as a conceptual riddle. The two videos in the exhibition, one a two-minute teaser, the other a three-minute trailer precisely edited to Hollywood convention, play in alternation, advertising a film about an artwork that may be hidden, forgotten, or non-existent. They also hold the status of this “coming attraction” in a similarly contingent state. In the teaser, Lawrence Weiner’s voice plays over a field of solid green, the same screen used for digital visual effects, or, on a film set, a placeholder for an image that will be added later. Like the white neon letters that served as both advertisement for and a standalone artwork in Bismuth’s 2008 exhibition “Coming Soon,” there’s no guarantee that the promised film that investigates the whereabouts of Ed Ruscha’s Rocky II, a fake rock planted somewhere in the Mojave Desert in 1976 (the date given in the teaser), actually exists. If an artwork is lost in the landscape, and there’s no film to corroborate its location, is it really there?

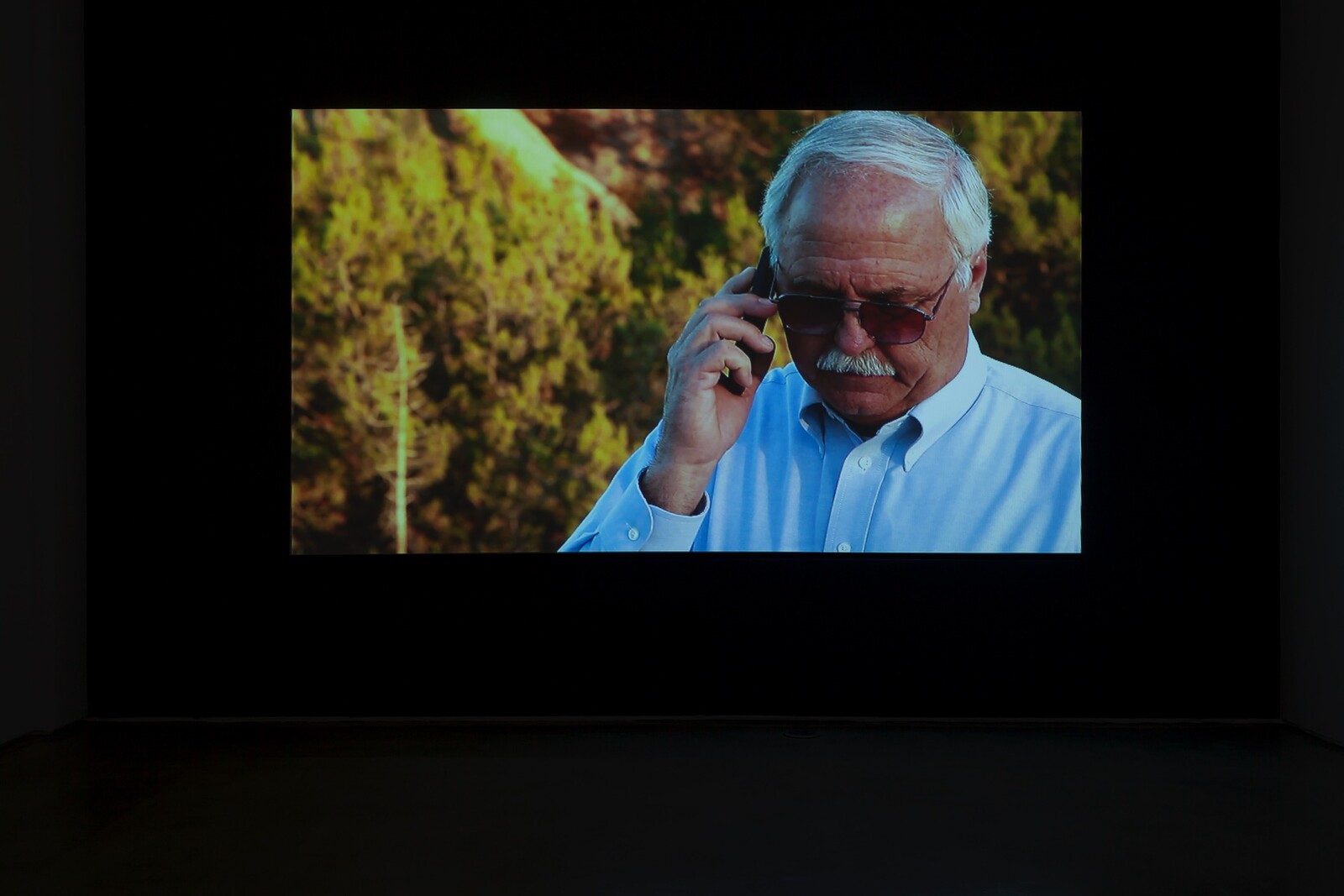

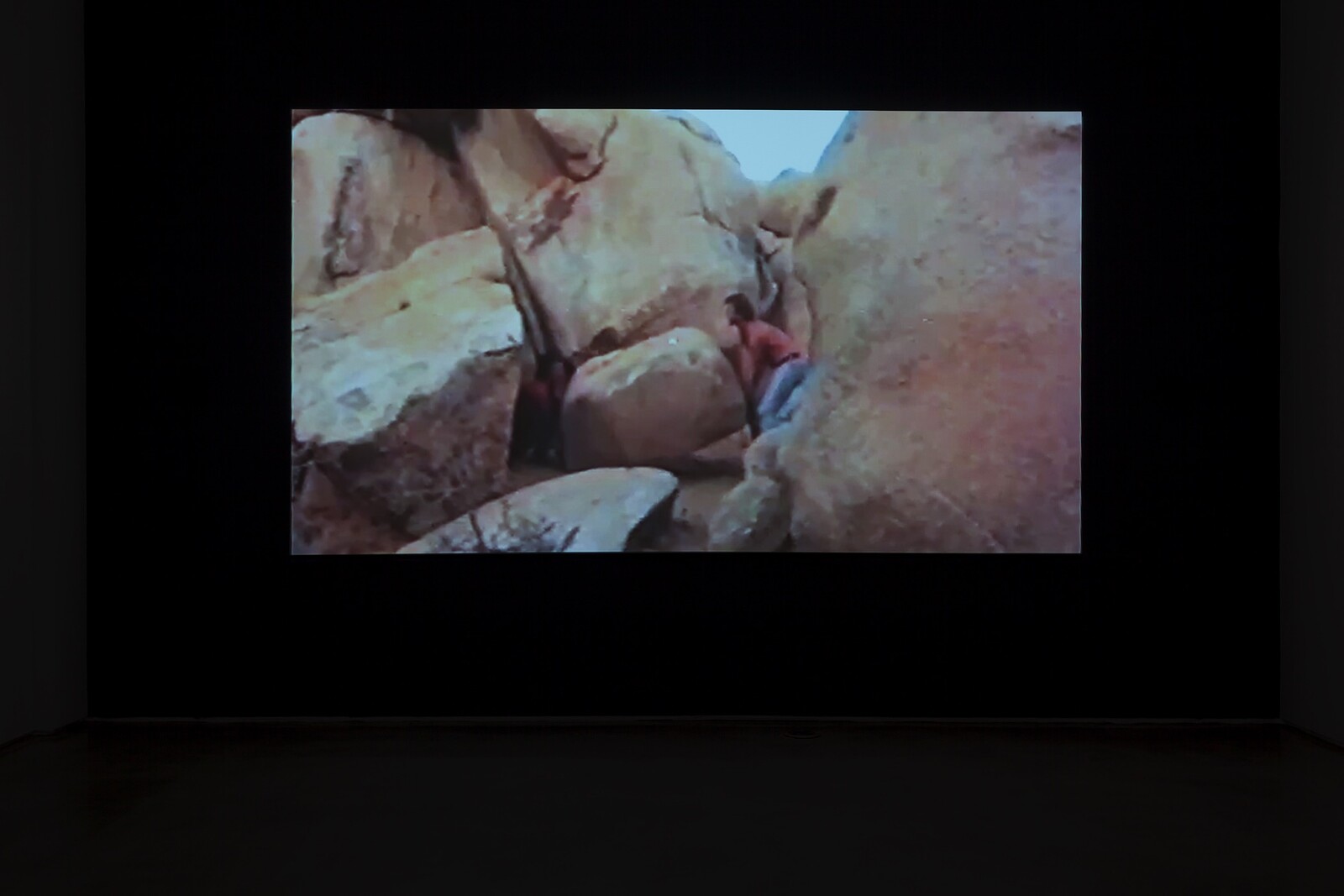

With Where Is Rocky II?, the answer is a tentative yes. Bismuth has been shooting a documentary, which, as the trailer depicts, follows private investigator and former Los Angeles County Sheriff Michael Scott as he interviews Southern California curators and pokes around Joshua Tree National Park, the alleged site where Ruscha placed the rock. Though Bismuth has been mum on whether Scott has successfully tracked down Rocky II, he has in the meantime collected roughly 50,000 dollars in finishing funds on Indiegogo, ostensibly to finance an accompanying fiction film, written by Hollywood screenwriters D.V. DeVincentis (High Fidelity and Grosse Point Blank) and Anthony Peckham (Invictus and Sherlock Holmes), that creatively interprets Scott’s investigation.

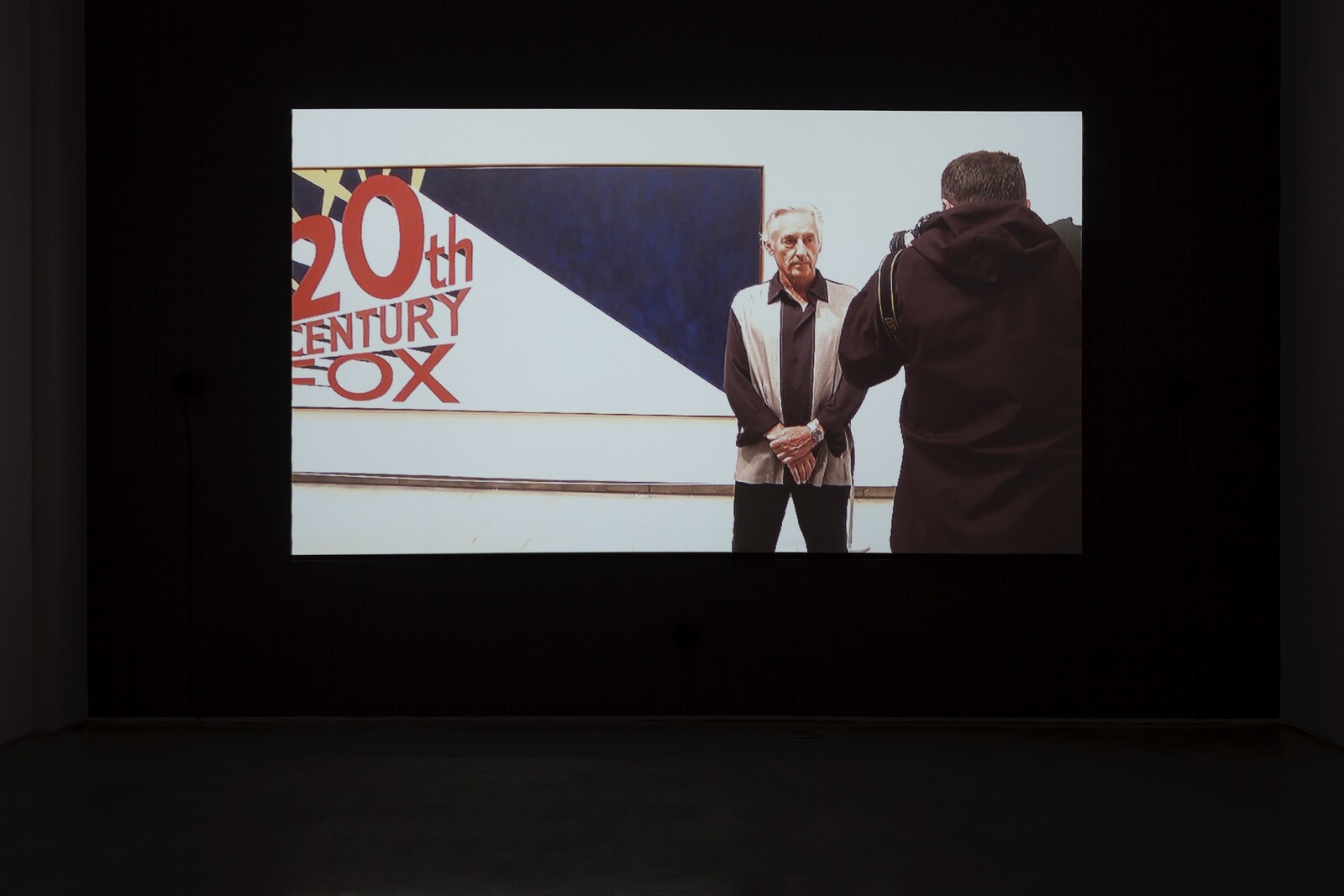

Experimental filmmakers, artists working with film and video, and pop-art provocateurs like Ruscha (who named Rocky II after the blockbuster Sylvester Stallone sequel) have long appropriated the language of mainstream cinema, but Bismuth is unusual for his history of direct involvement in Hollywood. The teaser cites Bismuth’s Academy Award-winning writing credit, shared by Michel Gondry and Charlie Kaufman, on The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and Where Is Rocky II? marks the artist’s return to commercial film 10 years later. The project is more than semi-ironic appropriation: while the teaser and trailer alone might, like the “Coming Soon” series, partake of the vernacular of mainstream movies (including, in the teaser, a riff reminiscent of the Mission Impossible theme song), the presumed existence of the feature-in-the-making changes this to a full-blown collaboration between Hollywood and contemporary art. This conditional meaning, which hinges on an object that may or may not exist, also characterizes Scott and Bismuth’s search for Rocky II. As Jeffrey Deitch, who is interviewed in the trailer, marvels, it is “reality and illusion mixed together.”

Cinema, of course, has always been a blend of reality and fiction, and the medium’s ability to do both is well suited to Bismuth’s playful thought experiments. On a broader level, though, what are we to make of this conjunction of Hollywood and contemporary art? The distinctions that once located art on the high end of the cultural spectrum while relegating film to mass-market kitsch have largely eroded, especially in an era of increased populist appeal, large-scale spectacle, and celebrity-cum-artist crossover in the art world. This has met with no shortage of consternation—Deitch’s stint as head of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles was particularly controversial for these reasons—though arguably the critique has less to do with a defense of art on aesthetic grounds than those wary of (further) commercial encroachment in the museum.

Hollywood is breezily called an industry, but the art world is far less comfortable naming itself a site of commerce. While both command a tremendous amount of wealth and resources, the contemporary art market is far cagier about its business dealings than Hollywood (and if the 2014 Sony hack is any indication, the film industry is terrible at keeping its secrets). Perhaps unintentionally, Bismuth’s search for a hidden artwork recalls the condition of many art objects that are currently locked away in freeport art storage spaces, accessible only to a privileged few. These warehouses, which Hito Steyerl, in her text “Duty-Free Art” called “secret museums” for their vast and unknown holdings, are located in semi- or extraterratorial zones where artworks are catalogued and held, tax-free, for an indeterminate amount of time.1 In such places, artwork are reduced to assets, and questions of form, style, and artistry matter only inasmuch as they contribute to its speculated worth. As freeports expand their holdings and more continue to be built, the works they hold disappear both from public view and as culturally meaningful objects. Invisibility, Steyerl argues, is becoming the condition for all art: art that is seen by no one.

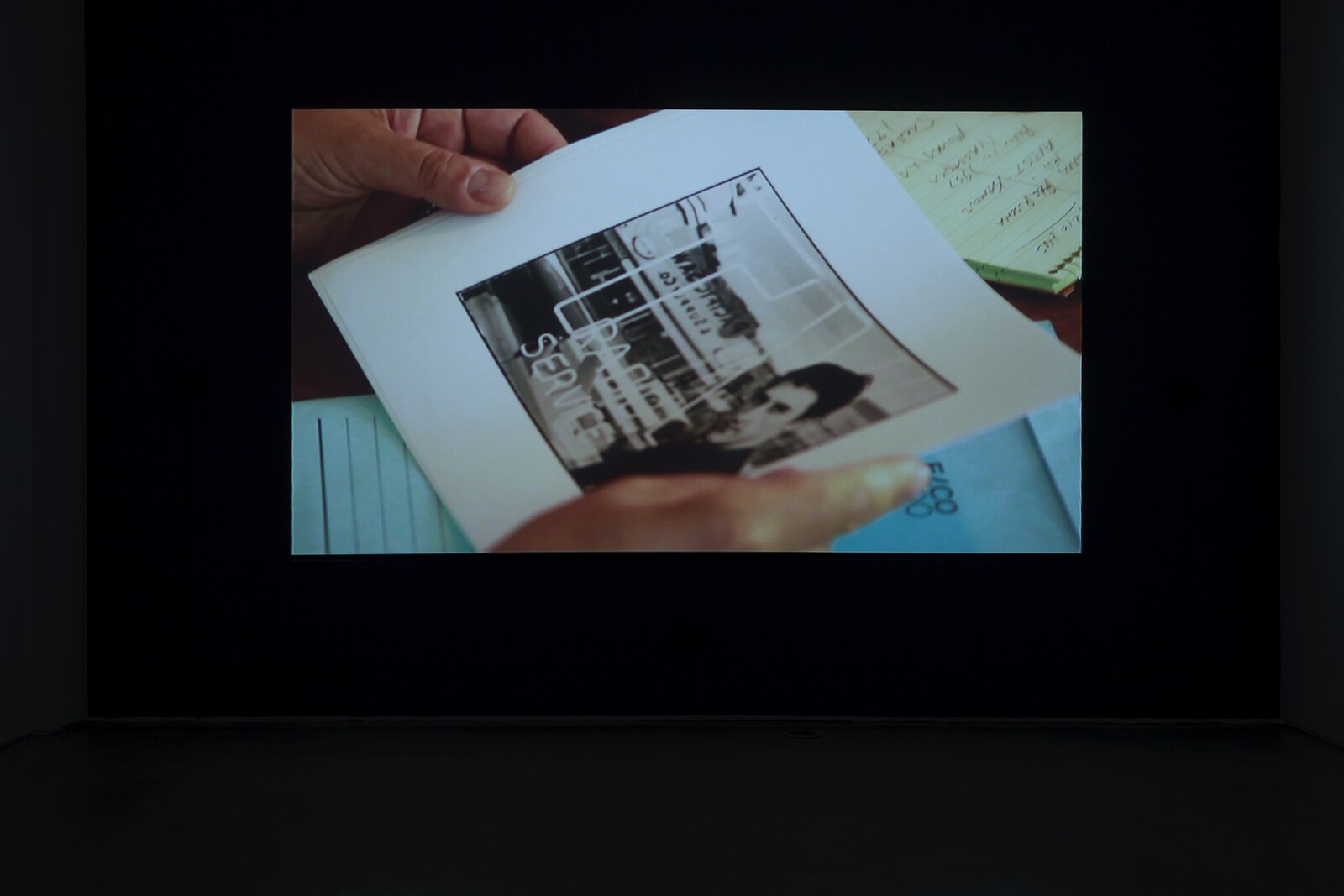

In the context of the contemporary art market in which Bismuth’s exhibition participates, it is hard not to read the desire to locate Ruscha’s artwork in Where Is Rocky II? symptomatically, as a response to art’s growing invisibility. This anxious undercurrent is not immediately apparent: the trailer’s jaunty tone is something of a cinematic throwback, and it presents the search as halfway between a noir detective thriller and a treasure hunt. Yet the questions posed by the film-to-be, and the exhibition’s alternating teaser and trailer, extend far beyond the hunt for a fake rock. At the beginning of the trailer, in an event that prompted the search for Rocky II, we see Bismuth posing as a journalist at a press conference with Ruscha. He asks: “in fifty years of painting, is there any work that has never been shown?” Ruscha responds, “I don’t exactly exhibit everything that I do.” In view of the current condition, in which few artists would seem to be able to exhibit all of their work, his remark seem less mysterious than possibly defensive, if not of himself, then the integrity of his work. Lost in the desert, here is one art object that can’t be bought, boxed, and sealed in a securitized art storage facility. As concepts, at least, Rocky II and Bismuth’s search remain insistently visible.

Hito Steyerl, “Duty-Free Art,” e-flux journal no. 63, (March 2015), https://www.e-flux.com/journal/duty-free-art/.