The slide projector last appeared in pop cultural consciousness on the television period drama Mad Men. Don Draper, pitching a fictional ad campaign to Kodak executives, clicks through a carousel filled with own family photos: his head leaning against his wife’s pregnant belly, his daughter sitting atop his shoulders. The poignancy of these slides is underscored by the knowledge that Don’s family life is falling apart. Nostalgia, he explains, means the pain of an old wound. The carousel is “a time machine… it takes us to a place where we ache to go again.”

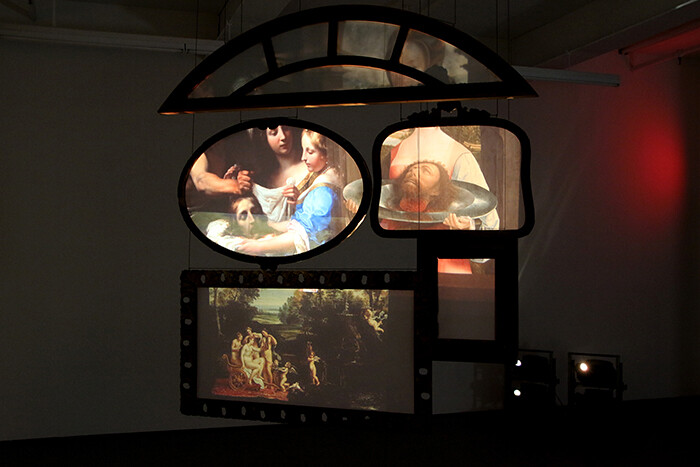

The carousel’s nostalgic twinge appears in “Slide Slide Slide,” an exhibition of slide projection works and related performances at New York’s Microscope Gallery. Older viewers will recognize the stout plastic machines from their childhood homes and classrooms. They are less familiar for younger audiences, for whom slide projectors have been replaced by their digital counterparts. This is evident in Bruno Munari’s Untitled (1, 2, 3) (1952), slide sculptures that, because of their curled ribbons that extend from the flat slide frame, are too delicate to be exhibited in a projector. In their place, images of the multifocal works are digitally projected as visual documents. Joel Schlemowitz’s A Gallery of Ektagraphic Elegies (2014), meanwhile, is comprised of slides rescued from the trash bins of the university where he teaches. It was through these images, reproductions of classical works of painting and sculpture, that generations of students learned the history of art. Here they’re rear-projected onto four mismatched picture frames strung from the ceiling, where the head of Solario’s St. John the Baptist slowly dissolves into and overlaps with Bouguereau’s cascading nymphs. Some of the smaller frames isolate details that are harder to place: a foot grazing the surface of a pond, the folds of a thick robe, a woman’s hand clasped to her bare chest. The work sways slightly in the circulating gallery air, effectively “moving” these still images and breathing into them a sense of (an after-) life.

The deaccessioned slides Schlemowitz recovered were originally meant for careful study. Luther Price’s Light Fractures (2013) also prompts a specific mode of viewing by limiting the amount of time each of its 80 images appears on the wall. Price’s slides last just long enough for a viewer to observe the photochemical distortions of color washes and cracked emulsions, and to glimpse beneath these manipulations the submerged photographic image of a windmill or a brick building before the image advances to the next. Like the saturated hues of nostalgia, the effect is one of impression. Price’s images, seemingly ravaged by time, momentarily appear as though culled from a dusty vault. Yet unlike memory, we’re not given time to linger. As soon as an image appears, it’s already pulling away from sight.

The slideshow’s obsolescence is only one aspect of the medium the exhibition addresses. “Slide Slide Slide” gathers practitioners who have some ongoing engagement with the projected image, including artists working with the sequencing of still images, or filmmakers treating stillness within moving ones. The result is a lively, even noisy exhibition: though all of the works are ostensibly silent, the projectors are surprisingly chatty. Often they seem to speak to each other, whether in shared themes like A Gallery and Light Fractures, or in the occurrence of common shapes, motifs, and methods.

Barbara Hammer, for example, re-edits her 1995 autobiographical documentary Tender Fictions into Identity Redux (2014), interspersing different shots of her mustachioed alter-ego, Bob Hammer, with title cards that, in all caps, demand the unfixing of gender categories. On the gallery’s opposite wall, Michael Snow’s Slidelength (1969–71) revisits, his 1967 work Wavelength, a film entirely comprised of a 45-minute camera zoom. Slidelength effectively “expands” the cinematic space of the previous film by breaking up its singular action into distinct stills. These are held on the wall for considerable time, alternating between quasi-documentary shots of the transparent gels as they were used in Wavelength, and closer-cropped views of the gels as full-frame, abstract color fields. Both Snow’s and Hammer’s works are shown without the context of their original films, though Slidelength fares better on its own. Its play of surface and depth contributes readily to conversations with other works about the materiality of the projected image.

Among these is Sandra Gibson and Luis Recoder’s Color Transparency (2014). Affixed to a lightbox and mounted on a translucent Plexiglas pedestal, the artists arranged rows of 35mm slides fitted with Rosco commercial gels normally used for color timing and analysis. The work is an “imaginary score for a color flicker film,” a sequence of reference color slides. The work’s visual musicality harmonizes with the exhibition’s sonic atmosphere, but it is the intensity of light in Color Transparency that dazzles. The small box shines like a beacon, its jewel and florescent colors glowing with the possibilities of the film they could be endlessly rearranged to make. Projection here is not a physical orchestration as it is with the other works, but—as always—an act of imagination.