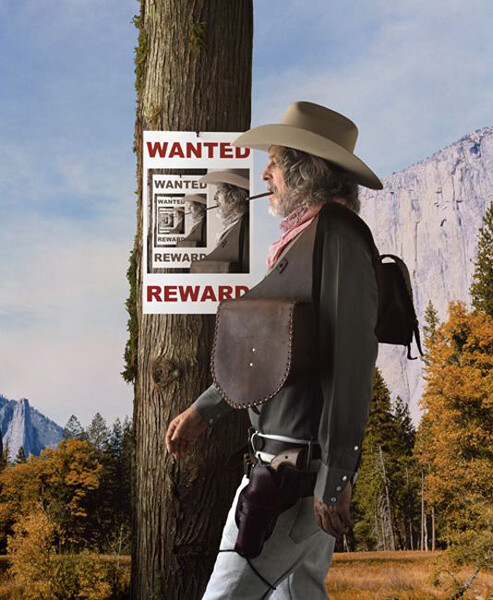

Since first stepping onto the other side of the lens in the mid-90s, Rodney Graham has fashioned himself as all color of amateur and outlaw in a wry game of wish fulfillment for an artist of inescapable renown. Cowboys, pirates, saloon men, and Sunday painters, these pseudo-egos follow the performative loops of their respective genres in films and lightboxes that Graham—the consummate citationist—appends with still other pop-cultural and esoteric references. Such densely layered work can make for stimulating (if maddening) viewing, much as Graham’s repeat billing can tilt from artistic reflexivity to self-infatuation. But if the trickster artist’s practice explores the innumerable ways that cultural history can be reframed, then any complaints about his ubiquity falter at the possibility that, like the mise-en-abîme of a wanted poster in Paradoxical Western Scene (2006), one frame merely invites another.

“Painter, Poet, Lighthouse Keeper,” the title of Graham’s current exhibition at Lisson Gallery, introduces several new characters whose creative lives are deeply marked by history. The lightbox Lighthouse Keeper with Lighthouse Model, 1955 (2010) depicts the lighthouse keeper in his maritime kitchen, at a time when automation was rendering his job redundant. Graham’s protagonist instead continues his work on a miniature-scale: a model of Minot’s Ledge lighthouse sits on a table just behind the lounging hobbyist, who inspects an illustration from a book of lighthouses that also happens to be the inspiration for the scene. This work is in keeping with the artist’s interest in the history of technology, but unlike the face-off of the unrelated, obsolescent 1930s typewriter and 1950s film projector in Rheinmetall/Victoria 8 (2003), it addresses a causal relationship between emergent machinery and outmoded human labor, giving socioeconomic weight to a deceptively quaint image.

Another series touches upon the careers of Alphonse de Neuville and Ernest Meisonnier, two French painters noted for their service in, and subsequent paintings of, the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71). In the excellent transparencies Artist’s Model Posing for ‘The Old Bugler, Among the Fallen, Battle of Beaune-Roland, 1870’ in the Studio of an Unknown Military Painter, Paris, 1855 (2009), Graham restages a book plate of de Neuville in his studio by assuming the role of a fallen National Guard infantryman and placing the viewer, implicitly, at the artist’s easel. A suit of armor, on display within the ornate, interior setting, provides a more distant, historical marker for the ever-topical transliteration of war into the field of aesthetics—a process Graham here performs with a straight face. Less effective are appropriated Meissonier pieces, which Graham has rotated sideways and silkscreened, in black-and-white, onto canvas. By turning two landscape paintings of battlefields (90 degrees) to a format normally granted to portraitures, Graham seems to ask that we see these copies as surrogates for their author, as well as for the many young artists who died over the course of the war. Yet such references remain oblique, at best, in these buttoned-up images, receiving far better treatment by the players and props of Graham’s photographic mise-en-scènes.