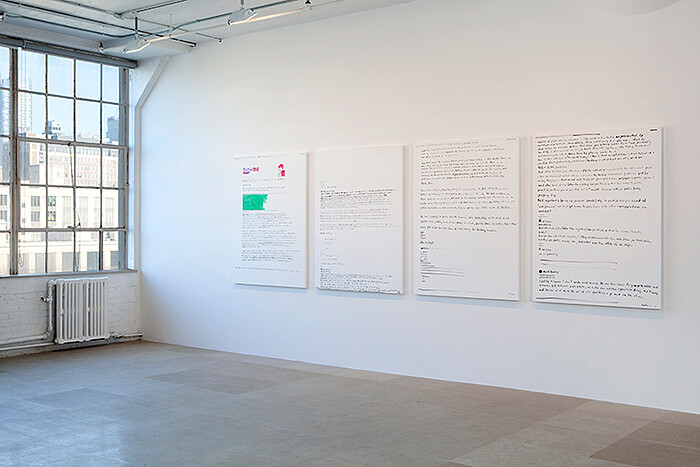

Let’s start this review typically, with a jaunty little narrative that encapsulates what’s happening in Michael Krebber’s latest show at Greene Naftali Gallery. Probably the most famous of Goya’s “Black Paintings” made between 1819-1823, painted directly onto the walls of his home at the time, the Quinta del Sordo (Villa of the Deaf Man), is that which goes by the name of Saturn Devouring His Children, one of six oil murals that adorned the dining room. (footnote 1) In his depiction of the myth of one of the Titans who ate his children in order to circumvent their youthful maneuverings in rendering him forcibly obsolete, Goya made Saturn’s eyes the focal point of the picture. With a crazed and bewildered look, the proto-Olympian gnaws on the arm of the headless corpse he clutches, less a deity in demeanor than a wild and formidable vagrant. Taken as allegory that transmits through the ages, adaptable and mutating, Goya’s work can fit any desperate world condition, but it’s Saturn’s eyeballs, with their lack of a gaze, or at least a pointed intelligence, that locate the horror and tragedy in the global contemporary art scene of 2011, and, in particular, in the paintings of young art blogs by Michael Krebber. Now for a bit of backstory: for some years now, Krebber has been a professor at a renowned European art academy called the Städelschule in Frankfurt, Germany. In the meantime, the art world has been coming to grips with the MFA higher art education phenomenon, and it has not been an effortless evolutionary process. While, on the one hand, there is a streamlining of formation, as some young artists emerge from these art school programs capable of leaping directly into the demands of curatorial and collector mechanisms; on the other hand, there is deep ambivalence in reckoning with the obvious demise of art’s bohemian, anti-academic tendencies since the 19th century. It is as if artists are no different these days from doctors or lawyers. There are jobs to be done, and people to fill those jobs, and somehow the colorful difference of the artist diminishes. By the way, long ago Paracelsus and Cornelius Agrippa were colorful figures of medicine, when it still had the tinge of the occult, before med schools and sanitation. Unfortunately, to continue to hold onto this ambivalence regarding standardization is a conservative artifact, one that is cherished by the official leftwing, counter-market aesthetic. Another such relic is the notion of the golden rule of anti-capitalism. To paraphrase the thoughts of Baudelaire—who said that the moment the bourgeois calls himself a bourgeois with disdain, the bourgeois as an antagonistic term is exhausted—to swear to be against capitalism today is a static, useless stance. (footnote 2) And this is the dilemma of critique today. If one is to read through countless art reviews in magazines and on websites, or on blogs, the writing with the most spark, the writing which does not function as creative replication of PR press releases, is the one that objects to something. All too often, this negation struggles for an ideology, a systematic scheme of ideas, and finds it in denouncing the contradictions of the market. (footnote 3) This leads to another contradiction: that of the elitist privilege of being able to recognize what’s wrong “with the market.” When once, not too long ago, I would have said I loved the art world, it was out of admiration and sense of attachment to this rarefied, complex space. Other people, the aspirational masses, were getting around to appreciating Richard Serra and Warhol, while I was digesting and reacting against Tobias Madison or Merlin Carpenter. Again, to throw these two names together is to recognize my stake in a complex, complicated body of knowledge, the MoMA one sees behind the MoMA, at least the one that crowds flock to on free Friday nights (sponsored by a department store chain). Calling out people on their complicity to the market in such a context is like seeking the abolition of money itself. It is a liturgy we all know, a comforting rite that fails to take into account how to begin to untangle the social relations of capitalism. What if I liked money, exactly for its alienation properties that free me from having to interact with everyone in society on a ground zero basis? And what if, nonetheless, I was committed to a violent, painful project of the restructuring of the system of distribution of wealth in that society?

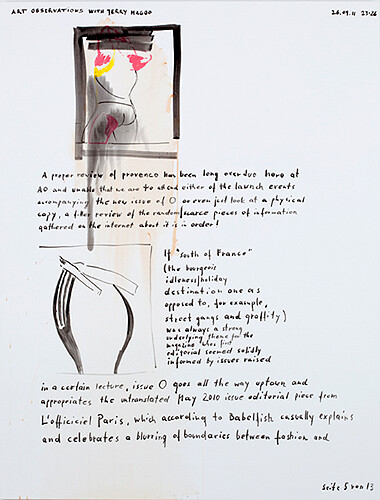

Rant aside and back to the blogs, and this is what Krebber’s show is ostensibly about, on paintings titled with the pseudo-materiality of web addresses. It’s about ranting, the ranting of those inculcated to be on the inside, my position exactly. On the Jerry Magoo blog, there’s the coinage of the term “Krebber Student,” which may or may not refer to a certain art-student assimilation of generic terms of blankness, disarray, non-communication, and a lack of preparedness that works today. Terms with which I don’t want to associate Michael Krebber (they could equally apply to other Greene Naftali artists such as Rachel Harrison or in a gross way to Bernadette Corporation, for all I care). Rather, Krebber performs the idea of art vampirism in its most exemplary form, with all the Twilight teen seduction to back it up. The vampires of Twilight are not dominant pigs; they are stealthy survival heroes, with flaws, hiding and assimilating their power, a model of resistance molded in an ancient, decadent framework of human ethics. In other words, it’s teen rebellion ditching high-school scene value for the Masonic lodge. A recapitulation of ethics, the vampiric quality is a symptom of art’s dilemma over reference, i.e., the artist regurgitating signs in game of look-at-me-here-and-now, extracting the world for audience consideration. Topicality in a well-meaning, general sense, like bloggers who identify with being bloggers. But for the semi-anonymous bloggers, with poisoned pen-names, called upon to unwillingly furnish content for a Krebber show—they find themselves suddenly represented by their objects of ridicule: commodities, paintings even. Somewhere there must be a bitterness even stronger than whatever useful resentment they had in telling it like it is, in saying the things no one said openly in the congenial fraternity of contemporary art. Something primordial, dripping from the historical milieus of “la vie bohème.” In that sense, Krebber is a monster, devouring his narrow art world, a glorified monster worthy of a painting by Goya, worthy of Goya himself, but with that dumb, blind eye. For all the speedy, technical freshness of the writing he appropriates and mirrors on canvas, Krebber congeals a monolithic endgame situation, malevolence at the limits of nothing, a masterpiece of a Städelschule stalemate. It’s the tolerated finality of a system that refuses to croak, even though this time, with this exhibition, it really does seem as if art gives its last gasp. This illusion alone proves that Michael Krebber is a brilliant tactician of complicity.