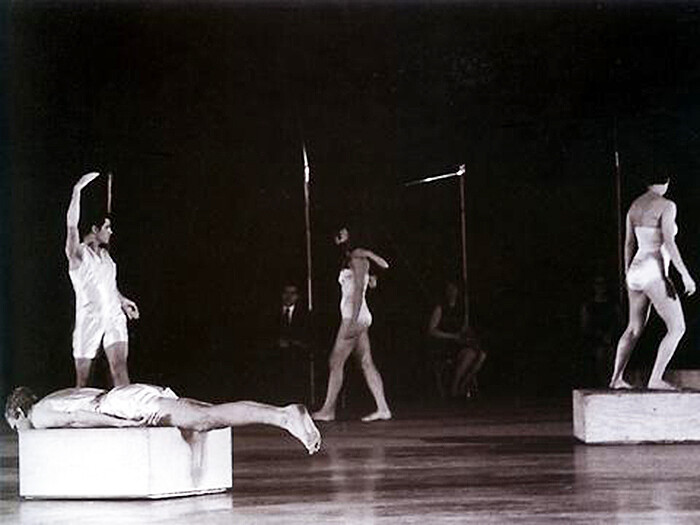

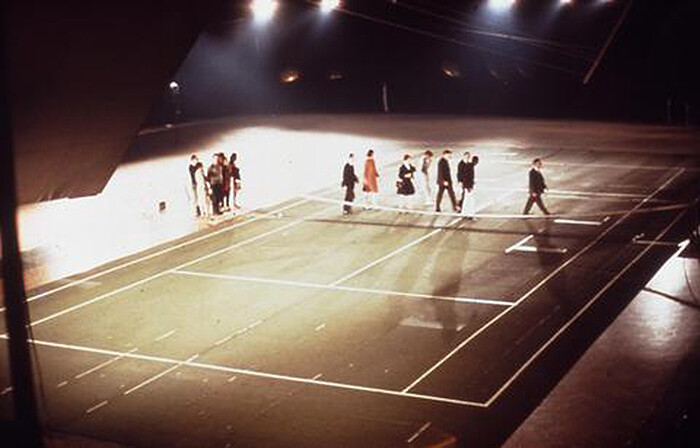

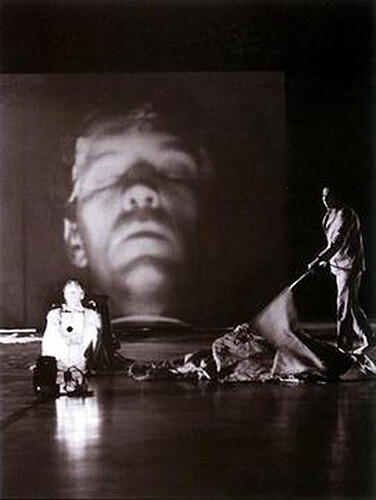

After stumbling across Robert Smithson’s vituperative response to a show that took place in 1966 at the Armory, I had to wonder what exactly it was that he saw. “Bovine formalism, tired painting, eccentric concentrics or numb structures”? His focus on the “funeral of technology” made me imagine that he’d seen a really bad Tinguely (which wouldn’t have surprised me) or maybe a bad Nam June Paik (which would). As it turns out, his ire was directed at an exhibition organized by Billy Klüver (an engineer) that included 10 artists, including Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Öyvind Fahlström, and Yvonne Rainer. Under the witty acronym E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) the performances, nonetheless, pioneered the way for the now-common practice of artists collaborating with practitioners from different fields. For the most part, the result of bringing 30 engineers together with 10 artists yielded performance kitsch at its worst (John Cage’s recordings of brain waves being the exception). You can watch a condensed (20-minute) version of the “Nine Evenings”: here.

—April Lamm

An Esthetics of Disappointment ON THE OCCASION OF THE ART AND TECHNOLOGY SHOW AT THE ARMORY

Many are disappointed at the nullity of art. Many try to pump life or space into the confusion that surrounds art. An incurable optimism like a mad dog rushes into the vacuum that the art suggests. A dread of voids and blanks brings on a horrible anticipation. Everybody wonders what art is, because there never seems to be any around. Many feel coldly repulsed by concrete unrealities, and demand some kind of proof or at least a few facts. Facts seem to ease the disappointment. But quickly those facts are exhausted and fall to the bottom of the mind. This mental relapse is incessant and tends to make our esthetic view stale. Nothing is more faded than esthetics. As a result, painting, sculpture, and architecture are finished, but the art habit continues. The more transparent and vain the esthetic, the less chance there is for reverting back to purity. Purity is a desperate nostalgia, that exfoliates like a hideous need. Purity also suggests a need for the absolute with all its perpetual traps. Yet, we are overburdened with countless absolutes, and driven to inefficient habits. These futile and stupefying habits are thought to have meaning. Futility, one of the more durable things of this world is nearer to the artistic experience than excitement. Yet, the life-forcer is always around trying to incite a fake madness. The mind is important, but only when it is empty. The greater the emptiness the grander the art.

Esthetics have devolved into rare types of stupidity. Each kind of stupidity may be broken down into categories such as bovine formalism, tired painting, eccentric concentrics or numb structures. All these categories and many others all petrify into a vast banality called the art world which is no world. A nice negativism seems to be spawning. A sweet nihilism is everywhere. Immobility and inertia are what many of the most gifted artists prefer. Vacant at the center, dull at the edge, a few artists are on the true path of stultification. Muddleheaded logic is taking the place of clearheaded illogic, much to nobody’s surprise.

Art’s latest derangement at the 25th Armory seemed like The Funeral of Technology. Everything electrical and mechanical was buried under various esthetic mutations. The energy of technology was smothered and dimmed. Noise and static opened up the negative dimensions. The audience steeped in agitated stagnation, conditioned by simulated action, and generally turned on, were turned off. This at least was a victory for art.

—Robert Smithson

Originally published in The Writings of Robert Smithson, edited by Nancy Holt, New York, New York University Press, 1979.

Text © Estate of Robert Smithson/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY