Few major exhibitions in recent memory have generated anything like the sort of intensely polarized response that greeted the recently concluded 9th Berlin Biennale, curated by the New York-based DIS, an increasingly notorious group of Gen X and Y “creatives” with close ties to the fashion and advertising industries. A recent publicity email from the Biennale explicitly highlighted this split, inviting readers to peruse the show’s “accolades” alongside its “viral backlash.” Yet despite this blithely mediaphilic rhetoric of all-press-is-good-press, the statement barely concealed a more defiant, even petulant message, evident in its illustration—a smugly confrontational photograph of a man and a woman wearing Yngve Holen’s Hater Blockers contact lenses (2016)—and its advertisement for a “soundtrack” mix by Isa Genzken and Total Freedom called FUCK THEM ALL (2016).

In presuming that any negative responses could be dismissed as mere hateration, the message positioned the Biennale as standing somehow beyond critique. This maneuver formed part of a more concerted defensive strategy in which the exhibition’s curators framed their product as immune to conventional forms of postmodern criticality, while simultaneously deploying their own bespoke, branded form of critical discourse, for example in a guest-edited issue of DIS magazine that attempted to theorize the “post-contemporary.”1

So if some critics hated the Biennale for its superabundance of fake-fetishizing, callow, now-chasing art, part of their disapproval might have come from the suspicion that they were being trolled.2 Like normcore––a similar exercise in mass-mediated provocation, one which read to many as an almost self-parodically obnoxious in-joke at the expense of the world outside New York City––the aesthetic of the Biennale was at once seemingly insouciant, resistant to definition, and far too cool for anything like school. To charge the curators with being jejune, superficial, apolitical, or cynically indifferent to their own privilege would be to out oneself as old, lame, or po-faced, all of which are toxic in an art world that is still much more image-obsessed than many care to admit.

Such a ruse frustrated criticism by frustrating critics, some of whom flatly wrote the Biennale off as nihilistic wankery, even if it also led others to hail the show as a brave strike against aesthetic and ideological uniformity, or as a kind of faux-affirmative immanent negation of techno-capitalistic power.3 What most of these responses tended to miss, however, was the way in which the Biennale exemplified what appears to be an emergent cultural logic. Speaking schematically, this could be described as the convergence of a particular aesthetic (the low-concept conceptualism of post-internet art, or whatever has already replaced it), a particular attitude (the affectless blague of non-criticality), and a particular economic conjuncture (the new forms of scaled customized production [“mass indie”] that have disrupted the purchasing patterns of youth subcultures, along with the luxury industry more broadly). To be blunt, the question is not just about whether the DIS aesthetic works, either as art, as fashion, or as some sort of post-critical critique; it is about what sort of ideological work it performs, insofar as it links creative labor and cultural production with new modes of desire, consumption, and subjectivation, and with new routes for the circulation of both symbolic and actual capital.

Its apparent bad faith notwithstanding, DIS makes a fascinating case study here insofar as its highly distinctive look corresponds with its self-defined role as something like a tastemakers’ media platform; while it makes some profit from selling image rights, branded merchandise, and artists’ editions, its real advantage derives from the ability to aggregate different content-streams into a recognizable aesthetic and a coherent knowledge base, assembling the kind of information for which branding and marketing consultants would gladly pay top dollar. Given this background, it was no surprise that DIS was chosen to organize the Biennale despite (or just as likely because of) its lack of mainstream curatorial experience—Berlin’s cultural officers must have seen them as the perfect ambassadors for its members’ efforts to shake the city’s image as a haven for leftists and slackers so as to rebrand it as a hub for hipsterized digital capitalism: the Brooklyn of the EU.

Some understanding of this larger context is necessary if we are to make sense of the recent successes of the young artist Simon Denny. Not only is Denny based in Berlin (his work was featured in the Biennale and attracted much attention); he has taken the city’s thriving IT industry as his subject in several works, which form part of a more general effort to track the profound social and economic transformations that technological change has effected over the last several decades. The ambitious scope of this project was visible in his 2015 New York debut at MoMA PS1, for which the 33-year-old Denny organized a mini-retrospective of his own work under the rubric of the popular business writer Clayton Christensen’s notion of “the innovator’s dilemma”: the tendency for established companies with a history of disruptive innovation to nevertheless misread the potential of new technologies. Provocatively organized on the model of a tech industry trade fair, the show sharply satirized the trouble that museums like MoMA have had in engaging contemporary art, even as it more anxiously questioned the fate of millennial artists whose youth and status as “digital natives” makes them both highly marketable and functionally disposable.

The pieces on view at PS1 aimed to repurpose the conventions of contemporary art to investigate numerous aspects of digital capitalism, including startup culture, corporate language and display, and pirate economies. One’s opinion of this work largely depended on whether one thought it suggestively reframed its appropriated referents, or instead merely reproduced them in a bid to leverage their contemporaneity for the benefit of the artist and museum. To this viewer, Denny’s most effective works have been those that exert the greatest torsion on what are by now overly familiar strategies: readymade assemblages that function as “portraits” of buzzy startups; installations based on corporate conference rooms; embedded “research” with tech incubators; a deadpan neoconceptualist investigation of Samsung’s corporate philosophy.

Yet while some critics have interpreted this work as a kind of Institutional Critique 2.0, along the lines of work by Carey Young or Melanie Gilligan, Denny’s public persona suggests a more ambiguous, conflicted, or compromised stance. In certain situations Denny has adopted what appears to be a subversive position; one thinks here of “Secret Power,” his contribution to the 2015 Venice Biennale, which used images surreptitiously commissioned from a former graphic designer for the US National Security Agency. In others, he has spoken in the bland generalities typical of much contemporary art discourse: he is “interested” in tech culture or “fascinated” by its contradictions, and tends to deflect questions about whether he is being sarcastic. In still others, Denny presents himself with what seems to be a completely ingenuous earnestness: “I am a fan of the culture of entrepreneurship. An artist is also a business… The values associated with entrepreneurship seem very close to me. Highly motivated people with high-risk precarious ideas mixed with efficiency and metrics. What could be more beautiful?”4

Given such an overt echo of Warhol (“good business is the best art”), or the fact that Denny has spoken favorably about “critical trolling,” one first wants to take him ironically, only to find this impulse stymied by all the evidence to the contrary.5 Denny has the credibility to be taken seriously by Texte zur Kunst, but he also has no problem speaking of his sincere respect for the advertising industry, glibly telling DIS about the contents of his DLD swag bag, or giving an interview to Bloomberg for a fawning video profile.6 Some might say that this speaks to his ability to locate contradictions in the discursive-institutional economy of contemporary art, yet while this might be so Denny’s mobility nevertheless comes at the cost of a fundamental compromise, in that his stance inevitably reads as one of noncommittal, easily recuperated quasi- or para- or post-critique.

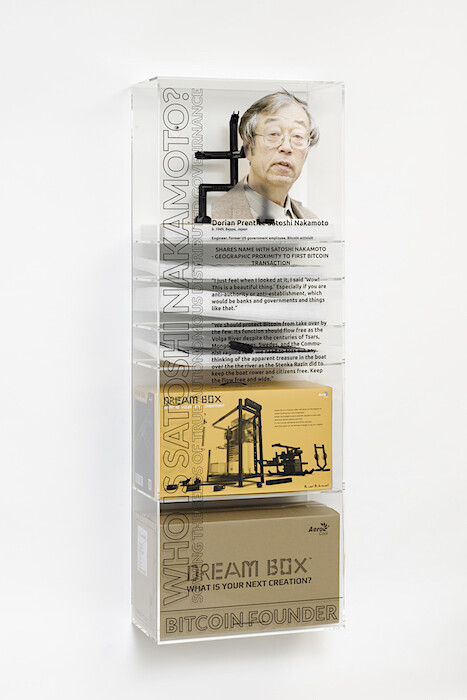

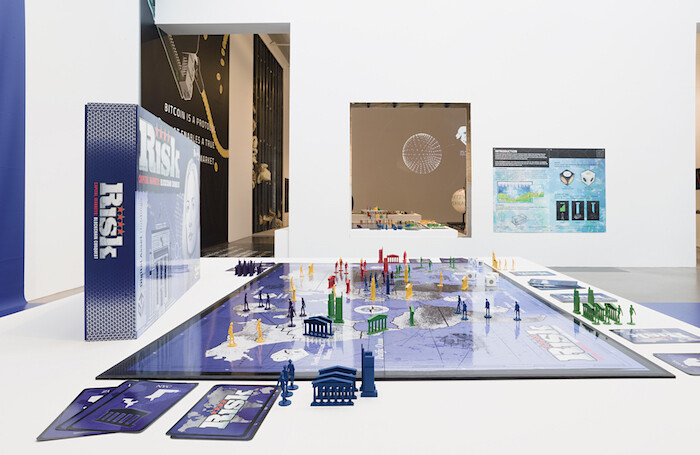

These questions were in full effect at Denny’s recent exhibition at Chelsea’s Petzel Gallery, which bore the vaguely accelerationist title “Blockchain Future States” and was based around work shown last summer at the Berlin Biennale. The show styled itself as a sort of introductory overview of blockchain technology—a mode of storing encrypted data across distributed locations, which forms the basis for the open-source digital currency Bitcoin. Denny’s timing was perfect, in that the extensive commercial and political implications of blockchain are just beginning to become broadly recognized, even as they have been obvious to tech insiders for some years now. It is clearly the moment to reckon with the potential impact of globally available encryption, whether in social, economic, or geopolitical terms, and to begin thinking through the ways that these changes will play out on the aesthetic level. In a rather transparently didactic gesture—whether earnest or ironic was, not surprisingly, somewhat tough to judge—the show functioned as a kind of primer, with one gallery devoted to the history and founders of Bitcoin, and the others to three of the most prominent blockchain ventures (Digital Asset Holdings, 21, and Ethereum). The basic premise, which likely struck some as clever and others as cutesy or patronizing, was children’s games: Pokémon for the Bitcoin sculptures, and Risk for the blockchain installations, which incorporated vinyl banners, larger-than-life, custom-made board game pieces, an infomercial-ish video projection, and wall cuts à la Michael Asher.

If, as above, one criterion for judging such art is its degree of formal re-inventiveness, then the Petzel show clearly fell short in that it either fell back on Denny’s previous methods or deployed underdeveloped new ones. Although there was plenty to look at and think about, much of the work seemed inert, lacking convincing evidence of effective mediation. One often felt beguiled, but much more by the subject matter than by its representation. It’s not that Denny’s project isn’t interesting or important—it genuinely is, and in a way that very little comparable art manages to be––but rather that it can’t quite live up to the expectations it aims to raise. The blockchain sculptures present us with what feels like petabytes of information, yet they aren’t especially informative, let alone argumentative. They come off like a beta test, leaving one wishing that Denny had done more research or thought more carefully about the kind of discursive site he means for his work to occupy. They make one wonder how the contemporary art world’s recent infatuation with acceleration relates to its penchant for overproduction, and about how the speculative risks that increasingly characterize art markets affect emerging artists.

In some sense these are questions about how we evaluate contemporary art, especially practices that work on or with new media. Does such work begin to register the more radical, unforeseeable consequences of technological transformation? Or is it merely content to document such changes, often in ways that surreptitiously convert their news-value into exchange-value? Is blockchain part of an emergent regime of deterritorialized cyber-capital, or is it the next Next Big Thing, a topical subject that helps the art market try to bridge the gap between its current demographic (the readers of Artforum) and another, eagerly desired one (the increasingly affluent and dominant readers of Wired)?

Like many of his peers, Denny doesn’t seem to want to choose, or to suffer the potentially unprofitable consequences of such a decision. For the moment, this strategy looks to be paying off: the blockchain work has received favorable notice not only in the Village Voice and the Guardian, but in the Wall Street Journal and Bitcoin Magazine. In a development that is possibly ironic but probably just fitting, Denny has recently been commissioned to produce work for the Zappos headquarters in Las Vegas. It seems likely that this venture will result in yet another piece of basically inoffensive corporate art, since in such a context the artist’s intentions are almost always effectively moot, whatever they might aspire to be. Such partnerships suggest the considerable commercial potential of para-critical tech art, which ultimately resembles nothing so much as the customized luxury RVs that Silicon Valley execs now routinely bring to Burning Man: it might look neat and be fun to talk about, but its real purpose is to give its owners a comfortable view of what once may have seemed like dissent.

See http://dismagazine.com/issues/post-contemporary/. DIS also commissioned a number of critical texts for the Biennale, which were grouped together on the Biennale website under the heading “Fear of Content.”

The most prominent example of such criticism came from Jason Farago’s “Welcome to the LOLhouse: how Berlin’s Biennale became a slick, sarcastic joke,” Guardian, June 13, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jun/13/berlin-biennale-exhibition-review-new-york-fashion-collective-dis-art.

For representative examples of these readings, see Mohamed Salemy, “Berlin’s Belated Biennale,” Ocula, August 9, 2016 (https://ocula.com/magazine/reports/berlin-s-belated-biennale-a-response-to-the-respon/); and Philipp Kleinmichel, “DIS-moralia: Reflections from a digitally damaged life,” Contemporary Art Stavanger, August 18, 2016 (http://www.contemporaryartstavanger.no/dis-moralia-reflections-digitally-damaged-life/).

“Artist Simon Denny Is Shaping Berlin’s Disruptive Startup Culture,” 032c, January 31, 2014, https://032c.com/2014/artist-simon-denny-is-shaping-berlins-disruptive-startup-culture/.

Simon Denny and Matt Goerzen, “Critical Trolling,” Mousse (April 2015): 190-205.

See Mathieu Malouf, “A Painting is a TV That Doesn’t Work,” Texte zur Kunst no. 85 (March 2012): 180–188; Timo Feldhaus, “The Soul of Simon Denny,” Spike, July 29, 2015, http://www.spikeartmagazine.com/en/articles/soul-simon-denny; “Artist Simon Denny on ‘Brilliant Ideas,’” Bloomberg, December 29, 2015, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2015-12-29/artist-simon-denny-on-brilliant-ideas-.