As capitalism solidifies into a global religion, iconoclasm—traditionally defined as the destruction of sacred artifacts—accordingly shifts its tactics, where it doesn’t become coopted. However inadvertent it may have been, the last notable iconoclastic act in Europe—“Beast Jesus,” an elderly Spanish woman’s attempt in 2012 to improve, while in fact defacing, a fresco portrait of its namesake—created a cash cow for the various parties involved. A more secular brand of iconoclasm in contemporary art has its famous examples—whether Tony Shafrazi spray-painting Pablo Picasso’s Guernica in 1974 or a 2006 hammer attack on Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain by a self-proclaimed Dadaist—that go alongside more conceptually oriented versions such as Robert Rauschenberg’s erasing of a Willem de Kooning drawing in 1953.

Just as every system contains the seeds of its own destruction, iconoclasm has erupted from within the current art world and even artworks themselves in response to their hyper-commoditization over the past decade or so. Recent projects have begun to address this at times literal fracturing of art as commodity object. Elka Krajewska’s Salvage Art Institute, which makes an appearance in Ben Lerner’s widely touted 2014 novel 10:04, presents works of art that have been rendered valueless (in some cases temporarily) because of damage to them. The project has photogenically presented a small-scale red Balloon Dog by Jeff Koons broken into pieces, but it also includes paintings with rips in their canvas, cracked sculptures, and photographs—a Henri Cartier-Bresson among them—with spots and stains.

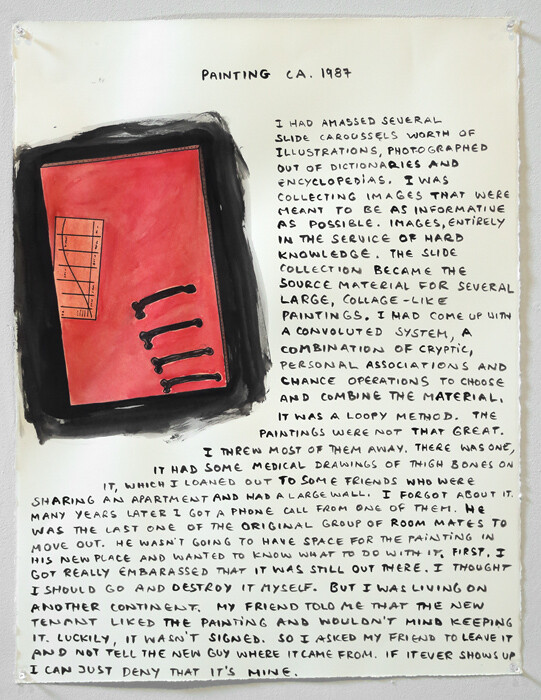

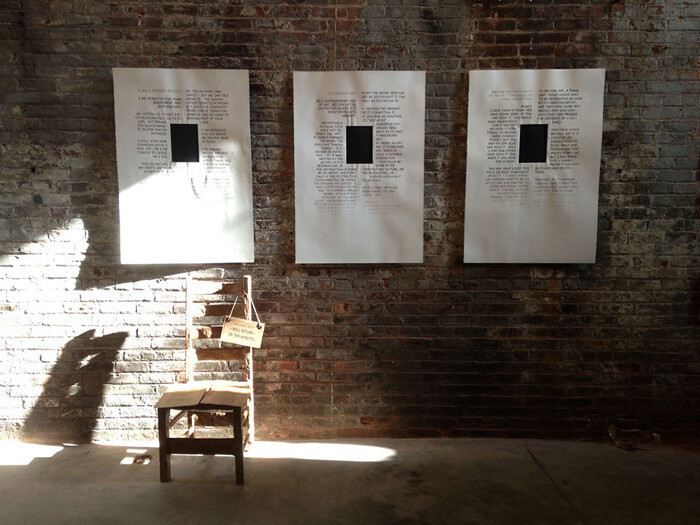

Relatedly, art writer Saul Anton and artist Ethan Spigland recently established the Foundation for Destroyed Art, which, according to its still-incipient website, “is a not-for-profit media archive devoted to the production, preservation and dissemination of destroyed artworks.” Its first project is the exhibition “Destroy, she said” at Pierogi Gallery’s Boiler space, which the two co-curated. Olav Westphalen opens the show with seven large drawings (all 2015) that describe in handwritten block letters a range of ways in which an artwork can be taken out of circulation: whether disavowed by the artist or disgruntled collaborator, poached for materials by other artists, physically damaged by audience or accident, or mistreated by institutions.

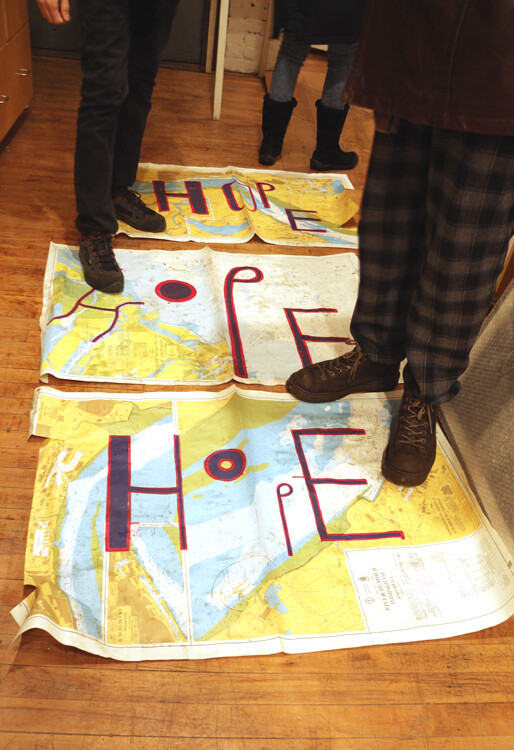

To reach his work, viewers must first step over—or on—Bob and Roberta Smith’s Destruction of “Maps of Hope” (2015) whose title succinctly describes the piece: three ripped-up maps with the word “HOPE” printed on them that are scattered across the gallery’s entrance. Of the dozen or so contributions to the exhibition, it’s one of the few that’s actually been destroyed—or, more precisely, its destruction has in turn been destroyed by gallery-goer treads, as opposed to being transformed into a metaphor or documented. A particularly good example of the latter is Nina Katchadourian’s Monuments to the Unelected, 2009 (2015), a video installation describing the necessary destruction of two signs—one for containing a typo, the other for being historically inaccurate (and then turning out to be historically accurate after all)—that formed part of her installation of lawn placards from failed presidential runs (e.g., “RE-ELECT CARTER-MONDALE”).

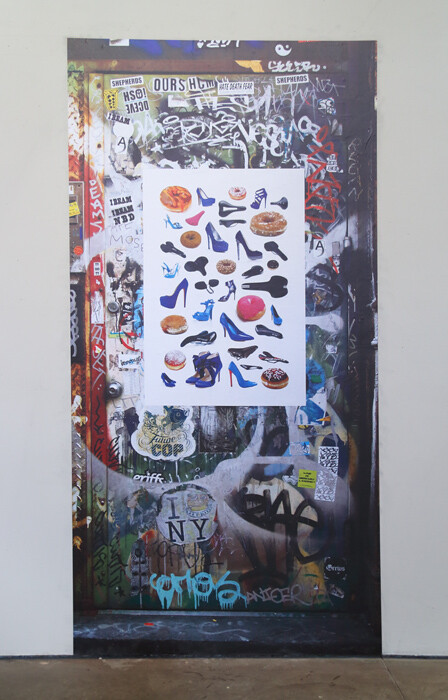

In other words, as with Krajewska’s Salvage Art Institute, the Foundation for Destroyed Art’s interrogation of the artwork as commodity object, or more generally as material object, can be slid into a long lineage of conceptual art projects, with an important difference being that artists of the 1960s and earlier weren’t confronting a highly optimized art market, and they certainly weren’t plying their trade within a world of managed artwork investment portfolios. No wonder there’s a new urge by artists to destroy things. At the Boiler, this may be a unique artwork, such as Kate Teale’s wall drawing, White Out (2015), which she is effacing over the course of the show, or part of an edition, as with Jeffrey Gibson’s Destruction of “Home Sweet Home” (2015), for which he took one from a series of ten prints clustering images of donuts and high heels and affixed it to his Williamsburg front door for passersby to comment on, tag, disfigure, etc.

But how do you really destroy an artwork? In Portrait (2015), which pairs a painted image of his partner with a digital slideshow revealing stages in its composition, Peter Rostovsky argues that the underpainting painting is eradicated with each additional layer. Perhaps the most intriguing answer comes from Ward Shelley. In a drawing forming part of his installation Destruction of “I Am a Hunger Artist” (2015) he states, “DESTROYING A PHYSICAL PIECE DOES NOT DESTROY THE ‘ART’, IT SIMPLY CHANGES THE WORK.” For instance, an artwork may remain in memory or be intentionally destroyed as part of a larger conceptual gesture. Instead, his contribution tells the story of a hidden painting made by his deceased mother that only she and he has seen. When his memory of it disappears, it will cease to exist—less tree falls in a forest, more ghost of a ghost.