“Migrating Forms” is easily New York’s most eclectic film festival. A glance at the program, now in its sixth year, can be dizzying: a half-inch videotape documentary from the seventies here, a Korean art film there, and all manner of experimental film and artists’ film in between. Instead of theme, we get range. The festival bills itself as innovative and inclusive, and it is. It’s a kind of weathervane sample of the past year’s moving image work, not tied to any particular culture, whether avant-garde film, the art world, or the subcultural connotations of its predecessor, the New York Underground Film Festival. Forms, as it were, are able to migrate freely, often in delirious and unpredictable ways.

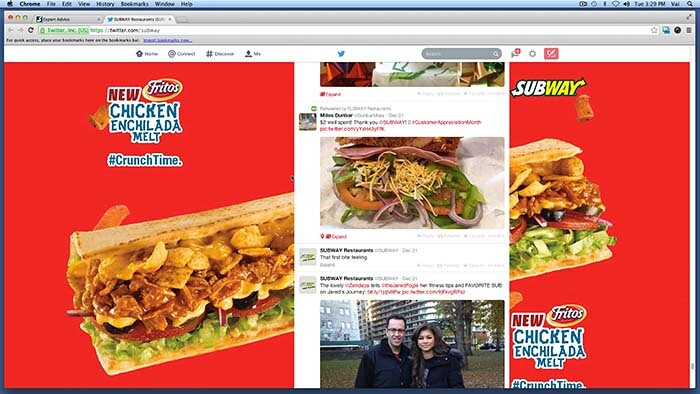

But it’s unclear whether such movements—across histories, institutions, and media practices—actually are that easy. Left unanswered is the question of what it means to serve up these various forms as if flipped through in the manner of a restless channel surfer—a metaphor all the more fitting for the festival’s ongoing emphasis on television, as evident in the accompanying sidebar program “Tube Time” showing at Anthology Film Archives. There’s undoubtedly value in creative disassociation, of stepping from Cory Archangel’s Freshbuzz (2014), a mesmerizing plunge into the vicissitudes of Subway’s website, to Rolf Forsberg’s allegorical Ark (1970), a dystopian sci-fi vision of an embattled Noah struggling to preserve life amidst a polluted, ruined landscape. It’s an unlikely itinerary, but there’s potentially much to be gained in seeing works that don’t often go together.

The bigger picture is one of increasingly blended spaces between art and experimental film, and how these “migrations” have transformed the meaning of previously distinct practices and histories. Where the film festival was once the mainstay of the avant-garde—as for example with the Oberhausen Short Film Festival, founded in 1954—this space has broadened to include the moving image work of artists, not only here, but at the newly renamed “Projections” at the New York Film Festival, the “Images” festival in Toronto, and almost every festival that specializes in non-narrative, short-form work. While many welcome these mutations of form (which are largely enabled and accelerated by digital technologies), what is concerning is the presumed equivalence—or at least uncritical examination—of the contexts through which they move. There is a gulf of difference between the international art fair and the storefront micro-cinema, and while there are many spaces in between, it is important to retain some sense of the way a film was made, who it was made for, and how and where it appears.

Two films—Gina Telaroli’s Here’s to the Future! (2014), and William Greaves’s cinéma verité classic Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) explicitly address these more reflexive aspects of filmmaking practice. Telaroli’s film-within-a-film depicts the restaging of a scene from Michael Curtiz’s The Cabin in the Cotton (1932). Her small crew, in addition to the camera equipment they wield, record their own footage on their phones and laptops, creating a mosaic portrait of collaborative filmmaking. Symbiopsychotaxiplasm similarly documents the recording process, though Greaves’s method is considerably more fraught. Having provided little direction to his actors or crew, Greaves’s team grows frustrated, bickering among themselves. One concedes that in their film the “director plays a different role than in other movies.”

Greaves passed away this August, and “Migrating Forms” pays tribute to his pioneering and under-recognized work, including Still a Brother (1968), a powerful and timely documentary about the black middle-class at the height of the civil rights era. Still a Brother began as a commission for public television and was intended to provide a view of black American life distinct from the images that pervaded the news at the time, namely race riots and protests. Greaves expanded the assignment to examine the subtle, but no less profound, changes in black middle-class consciousness that allowed many of its members to join the cause of civil rights and black pride.

Many of the works at “Migrating Forms” address the conditions of Internet viewing and experience. This is the condition of contemporary film critics as well—as with any festival these days, all of the films available for preview were screened online, not in a theater. Jacob Ciocci’s The Urgency (2014) is a frenetic and often sinister catalogue of Internet affects. Terror, anger, and despair are unleashed in a cacophonous montage of YouTube videos, rudimentary computer graphics, and détourned fragments of popular culture. Rachel Rose’s A Minute Ago (2014) similarly expresses the more ominous, even apocalyptic undertones of Internet media. In it, a clip of a freak hailstorm that erupts on a beach scene is intercut rapidly, glitch-like, with images of a blurred man walking through the Philip Johnson Glass House, suggesting that no place, certainly not a structure made of glass, will provide adequate cover for the coming storm.

True to form, many of the films at “Migrating Forms” provide access to other, often imagined spaces. With Stanya Kahn’s Don’t Go Back To Sleep (2014), doctors set up triage facilities in newly built, but still empty, luxury high-rise apartments in Kansas City, Missouri. These unfinished real estate developments form the site of an implied capitalist disaster with human casualties. Soon-Mi Yoo travels to a different kind of space in Songs from the North (2014). Her several visits to North Korea are driven not only by her curiosity for a country that for so long remained closed to outsiders, but also an implacable longing. For her and South Koreans like her father, North Korea is an open wound that refuses to heal. She compiles footage from North Korean films, propaganda plays, and long, searching shots of the people she meets. These faces are as mysterious to Yoo as they are to us, ciphers that no camera could ever exhaust. The task Yoo sets for herself, and the one that hangs over the viewer in all of the festival’s many forms, is to continue searching the image, to look at and into it, even as it disappears from view.