When Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa was unveiled in the Paris salon of 1819, there were gasps of horror (and low whistles of admiration) at its political audacity. The painting depicted a public scandal of just three years prior, the tale of a slave ship stranded at sea and then abandoned by its incompetent state-appointed captain. The painting’s stark contrast of despair and hope—a monumental composition of contorted bodies capped by a figure who has just spotted a ship on the horizon—eventually cemented Géricault’s reputation within the Romantic movement.

The painting’s dramatic emotional heroism made it a natural choice for a project by Martin Kippenberger, as source material for an appropriation that combines parody and respect in equal measures. A restless and prolific artist, Kippenberger extended (and undermined) the legacy of Germany’s Pop forefathers through his excessive gestures and a larger-than-life persona. He returned again and again to painting as a medium, and a year before his premature death in 1997, he produced a multi-part project based on Géricault’s painting. Given that it was one of Kippenberger’s last cycles of work, the concept of death has become the inevitably intertwined with its interpretation.

The recent exhibition at Carolina Nitsch features a small suite of lithographs from that series (which had included paintings, prints, and even a carpet), supplemented with a handful of drawings and collages, an artist book and a poster. The result is a visual experience that, like much of Kippenberger’s work, speaks differently to those acquainted with his approach than it would to a casual viewer. While the striking weirdness of his visual style needs no emphasis and his skills as a draftsman certainly hold their own, the underlying force and motivations behind his work are more difficult to retrieve.

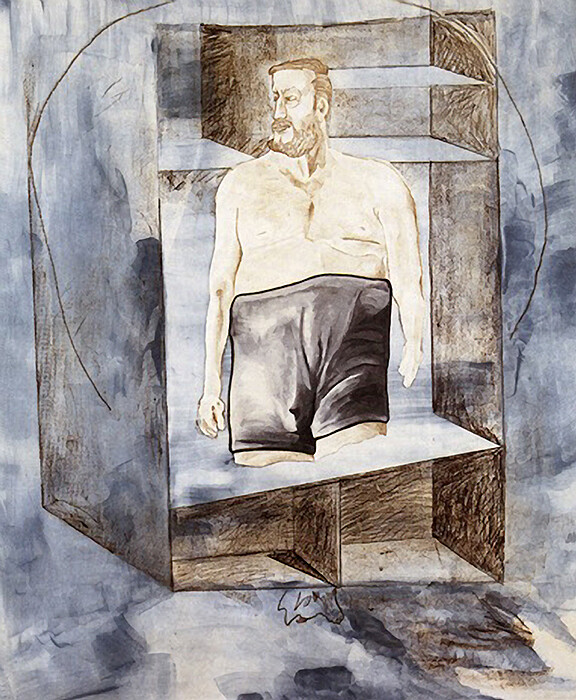

The lithographs of “The Raft of the Medusa” are spread across two walls, expressionist drawings that show the artist assuming the tortured poses of the original painting, mercilessly exaggerating his flabby body and sunken face. He looks despairingly at the sky, waves awkwardly at a passing ship, or falls dejectedly on the ground, re-enacting the rise and fall of hope through gestures that veer undecidedly between tragic and pathetic. The pathos of the figure is less the result of the poses than his expressive drawing style: waveringly fragile lines give way to dark outlining, roughly scratched masses play against thin washes of paint. Two of the prints show the figure boxed into wine or beer labels, as if to confirm the viewer’s growing suspicion that rather than the plight of humanity, the artist is enacting his own entrapment in everyday vices. The appeal of the work may well lie precisely in its deliberately ambiguous negotiation of the metaphysical, the political, and the utterly banal.

The works that supplement “The Raft of the Medusa” give plenty more of the narcissistic philosopher of the mundane. A self-portrait from 1997 of Kippenberger stripped down to his boxers (a colossal pair that contrasts dramatically with his drooping torso and steely expression) could be based on the oldest work in the show, the ELITE ‘88 (1988), open to a page that shows the artist posed in the aforesaid boxers, staring into space with a dreamy expression. The show as a whole rehearses the theme of abject exhibitionism by including a number of self-portraits, some relatively straightforward, others playful appropriations—as in his smudgy pencil drawing of a Cindy Sherman photograph of Sherman as a clown, inscribed in a childish hand: “Cindy as Martin.”

There was more to Kippenberger than self-reflexive portraiture. But the complicated, messy Kippenberger, the impresario of many mediums who never seemed afraid to fail and has many awful works to prove it, is a ghost in the room here. “The Raft of the Medusa” is a slice of Kippenberger at his most coherent and skilled, weaving a balancing act of desperation and showmanship inspired by a painting that set the standard for scandalous truth telling in its day. What is missing is the scope and significance of the way he questioned the very role of the artist as a teller of disturbing truths, after painting has lost its power to tell stories on the scale of, say, a Géricault. To grasp the dimensions of Kippenberger’s political audacity, and for the larger narrative behind this image of the artist as anti-hero wildly waving a flag at a very distant ship, viewers will need to delve into the larger body of work that serves as the invisible backdrop to this show.