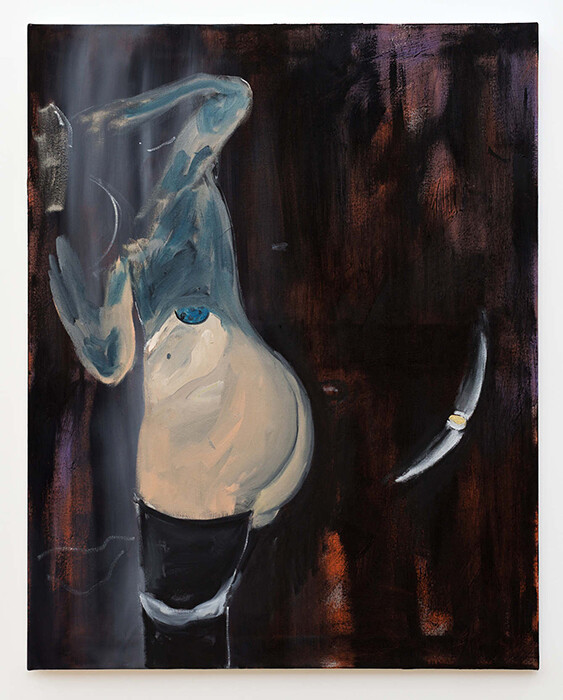

Of the six paintings that make up Jeanette Mundt’s “Heroin: Cape Cod, USA,” three render figures of women at rest. Of these, Jeanette Mundt (all works 2016) is a self-portrait; we see her body contorted into the archetypal pose of the butt selfie: the back side of her body facing the plane of the image, with shoulders and head twisted around to point the camera. Here, in their translation from photograph to painting, the artist’s hands, face, and camera (phone)—what’s typically a dense site for information—are obscured by a greyish specter, left unarticulated. In the hands of another artist the gesture of painting a selfie might feel cheap, but Mundt—simultaneously painter, photographer, viewer, and model, both subject and object—gives it grace, teaching viewers how to see a body seeing itself.

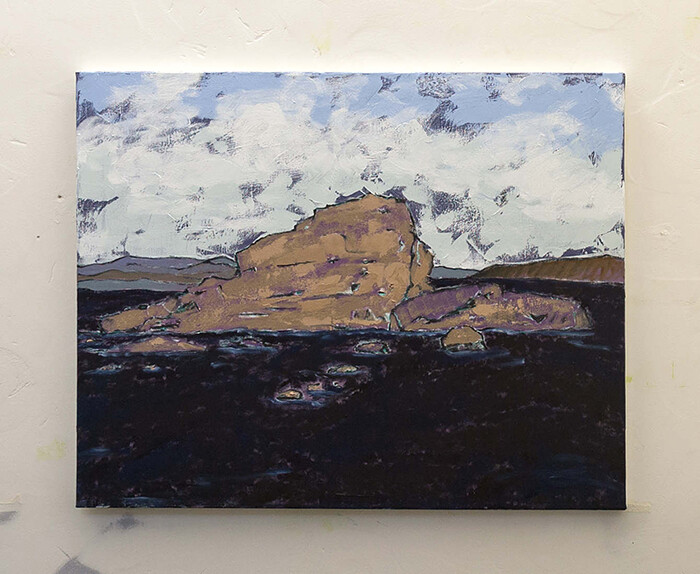

The scope of the adjacent artwork (Another Double Mountain and the Modern Sofa) feels radically different, with a sort of ugly modernist sofa affixed to an upright painted panel featuring the Alps’ Matterhorn. In the painting, the mountain’s blue peak is reflected in the waters of a deep pool at its base, with bands of paint leaking downwards. A second smaller slope bisects the image, supersaturated with rust, ochre, and peacock green. Representing the Matterhorn is more the province of a nineteenth-century landscape painter than that of one based in New York in 2016, and the appendage of a mid-century couch amplifies the work’s anachronism. Distinct from historical renditions, however, Mundt’s Matterhorn is in conversation with the fact that the iconic peak lends its image to a Disneyland rollercoaster as well as to a tourist industry that streams billions of dollars annually into notoriously tax-evading Swiss bank accounts. Alongside The Revenant, which the mountain range faces in the gallery, Another Double Mountain might be understood as an exercise in working through the nationalist narratives—clichés among them—to which the artist, having grown up between Switzerland and the US, has been subject.

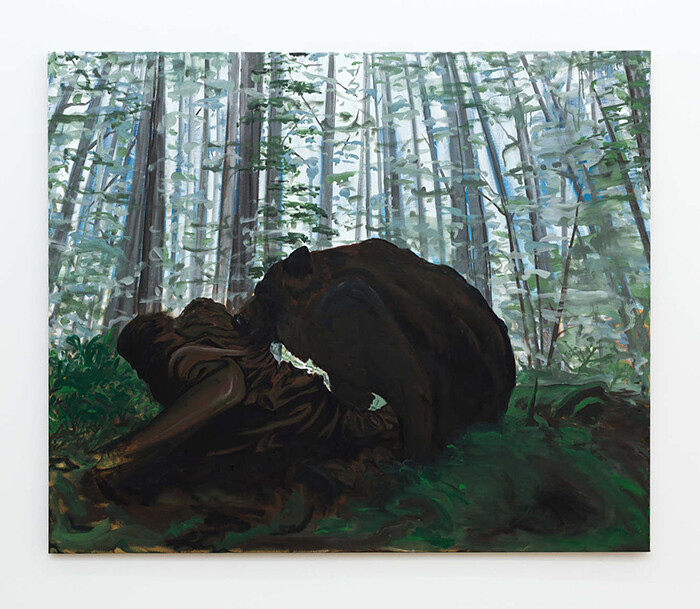

The Revenant reproduces in paint a film still from the eponymous movie, released last year: the colonial drama writ large and expensive. The film’s protagonist is real-life nineteenth-century American frontiersman and fur trapper Hugh Glass, who, after being attacked by a bear and abandoned by his collaborators, seeks violent retribution. History is malleable in the hands of those who have profited from it, and Glass’s story, among others, has been re-imagined in retrospect in service of an evolving American colonial imaginary many times over. In Glass’s lifetime, the narrative celebrated his spirited endurance; in the twentieth century, it came to represent a time before the frontier was closed. This most recent iteration sees Glass redeemed in bloodshed, becoming whole through brutality. In Mundt’s painting, two brown shapes, roughly those of a man and an animal, wrestle on the forest floor.

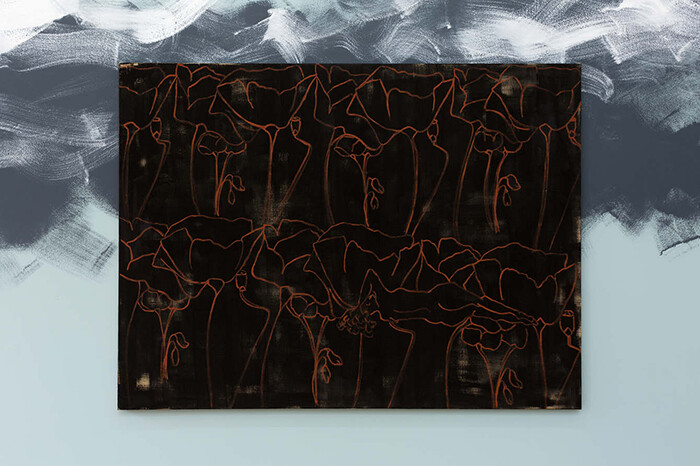

One of the gallery’s walls is painted a continuum of a light, generic blue, over which dark blue and white are roughly applied, a shorthand for clouds. Hanging directly on this surface is Passed Out in the Poppies, whose black background hosts two rows of flowers simply sketched in red. Among these a woman lies prone, though her outline is not immediately visible against those of the poppies. Her inconspicuousness reads like at first like a happy privacy—the luxury of being naked, yet unseen—but whatever measure of peace this affords her becomes more sinister in light of the poppies’ psychoactive properties. The exhibition’s title, borrowed from a 2015 HBO documentary of the same name, tracks eight young heroin users living in the Massachusetts peninsula whose experiences presumably speak to the reality of America’s opioid epidemic, which is currently reported to claim 125 lives a day—a rate nearing that of H.I.V. at its peak mortality. Made by the same producer as the 1999 documentary Black Tar Heroin, the film is said to be especially harrowing; the gallerist warned me not to watch it.

Fixed upright by an armature of steel pipes, Climbing formally mirrors Another Double Mountain with a similar painted wood panel; in this case, it’s carved into the silhouette of a woman nude and kneeling on a bed. What she’s doing isn’t especially legible; it seems like she’s making the bed but it could be something sexier. As with the exhibition’s other intimate portraits, it’s difficult to place her in relation to Mundt’s icons of nationhood or masculinity, other than to think of her as a picture of what it’s like to live among and through the latent structures (including art historical ways of seeing) that give and take meaning from the lives of women.