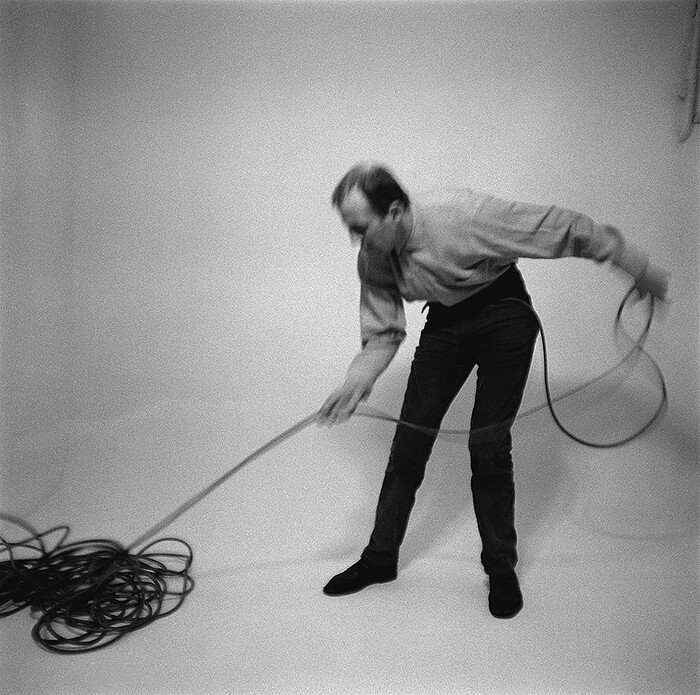

Edward Krasiński and Eustachy Kossakowski were friends, artists, and key members of the Polish neo-avant-garde of the 1960s and 70s. Their recent exhibition at BROADWAY 1602, titled “J’ai perdu la fin!!!” (I Have Lost the End), is a retrospective of their collaborative work. Nearly a hundred small, framed black-and-white photographs, often organized into series, show Krasiński staging a gesture, setting up a sculpture or performing an action for Kossakowski’s camera, in endless variations of an artist making lines out of rubber, wire, string, and, yes, his familiar tape.>

The photographs are accompanied by a few examples of Krasiński’s sculptural work: the 1969 Bobbin, for example, a blue circle being unraveled and wound into a bobbin of blue thread (or vice-versa), and the three geometric abstract reliefs titled Interventions (of 1981, 1992 and 1994) that open the rectangular frame of a painting onto space. But the Interventions, like many of Krasiński’s objects seem like mere supplements to his greater work—the famous blue line.

For better or worse, Krasiński’s career has been defined by a single concept, described in his own words as: “Plastic tape Scotch blue, width 19 mm, length unknown. I stick it horizontally on everything and everywhere, at a height of 130 cm.” The photographs prove that he really did stick it everywhere: walls, objects, trees, people, even the air. With the blue line, Krasiński underlined everything and anything. Tipping his hat in the direction of Duchamp’s readymades via Yves Klein’s monochromes, his line was much less structured than either of them. The blue line instructs the viewer to look closely, to follow its trajectory as it connects things, people or events. In its actual form, the work calls for the same blue packing tape favored by housepainters and art packers the world over. Scotch Blue is matte, somewhat papery, and known as a gentle adhesive that minimizes damage to the surface underneath. Most importantly, it looks as utterly forgettable today as it did in 1968.

At 1602 Broadway, the blue tape winds its way from the side gallery, through the main space into the back office. The resulting line connects Krasiński’s earliest outdoor sculpture-performance, the floating line/cylinder of his 1964 Dzida Wielka/Spear, Zalesie to his famed Warsaw studio, circa 1970. The two groups of photographs bookend a dynamic period in the artist’s career, as he moved from kinetic sculpture to a more specific interest in spaces and sites. His studio—which Krasiński shared with Polish Constructivist Henryk Stażewski until the latter’s death in 1988—was a home, a workspace, a meeting point for several generations of Polish artists, and a life-work in the tradition of Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau.

But the studio photographs speak less of a grand vision than a quiet intimacy with objects and work. Krasiński’s approach was deeply rooted in the private sphere, with few references to urban spaces of communist Poland. His objects inhabit a setting but refuse to define it. It is only by comparing the object in the gallery and its photograph in the artist’s studio that the nature of this refusal becomes clear. The blue and white cylinders of the 1969 Tubes, for example, look crude and provisional in real life—the wire that connects them could be an electric cable casually left on the floor. In the crisp black-and-white of the photographs, Tubes bears all the hallmarks of canonical post-minimalism awaiting discovery. Taken together, the object and its photograph present the line as a metaphor of open, unstructured connectivity.

The discrepancy between object and photograph is one of the most revealing aspects of the Krasiński-Kossakowski collaboration. While many conceptual artists claimed to have “dematerialized” the art object in favor of the concept, few of the resulting works have managed to remain as banal as the day they were conceived. The most everyday objects become rare souvenirs of another time, and the most functional text pieces mellow into sheets of obsolete typewriter script and precious handwriting. The masking tape, however, is just that. Unremarkable and sticky, it is a highly appropriate realization of a line—by definition, a connection between two points. If the photographs represent the concept of the line, the objects emphasize how its actual materiality is of secondary importance.

“The tape… mustn’t be beautiful,” Krasiński once protested, “I hate beauty!” But Krasiński’s conceptual gesture could be both beautiful and moving. This is in no small measure due to Kossakowski’s skills: as a press photographer, he knew exactly which moments to seize and how to frame them. Their collaboration hinges on the double edge of Krasiński’s work: while the objects can look awkward, ungainly, and absolutely ordinary, the classic reportage look of the photographs gives them the instant aura of history and materiality. By presenting the same body of work in two mediums, the exhibition provides a clear picture of what it means to privilege concept over form and its many ramifications.