Simon Starling returns yet again to the career of Henry Moore in Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima) (2010), currently on view at Casey Kaplan, New York. The film traces the troubled history of the British sculptor’s monument, Atom Piece/Nuclear Energy, from its 1967 installation at the historic site of Chicago Pile-1 to the Hiroshima City Museum of Art, which collected a bronze model in 1987. Moore died a year before the acquisition, though he was already caught in political back-pedal. A 1970 photo shoot staged the sculptor at work on the finished model, next to an elephant skull—comparatively neutral, considering the mushroom clouds and human skulls of actual influence.

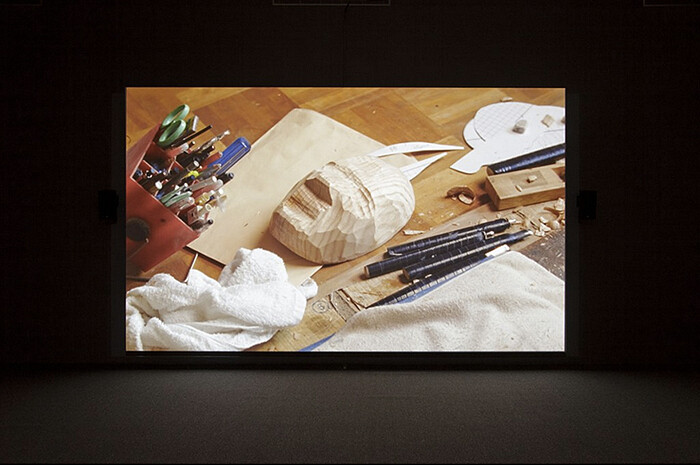

Starling begins with a name. At the outset of the film, an Osakan mask maker planes “Moore” off a wooden block and whittles the enchanted object down to the sculptor’s face. This mask is joined by fellow Cold War likenesses, shown in partially-completed states, including Pile-1 orchestrator, Enrico Fermi; James Bond; Anthony Blunt; and the opposing faces of the Moore monument. While the camera attentively follows their making—never straying from the craftsman’s studio—a voiceover imagines the finished masks taking positions on the Noh stage. Adapting the 16th-century play “Eboshi-ori,” Starling casts Atom Piece/Nuclear Energy as a defeated clan’s son, who, to escape servitude, is disguised by hat maker Moore. A sculpture thus seeks emancipation from past symbolism, in a potent allegory needlessly bloated by Starling’s fancifully extraneous cast members and understudies.

A separate film, Black Drop (2012), also documents a site of manufacture, where an editor assembles Starling’s 35mm footage of this year’s transit of Venus across the Sun. The film stock lends a material urgency to the phenomenon, which arises in eight-year pairs roughly every century: this transit will be the last of our lifetimes and, possibly, of the medium itself. The coincidence is made all the more significant by Starling’s connection of the phenomenon with the history of the cinema. The English artist, for example, exposed his stock at one frame per second—the same rate used to capture the 1874 transit, on the plates of Jules Janssen’s revolver photographique.

Starling plots Janssen’s invention as one in a long series of scientific attempts to measure the mean Earth-Sun distance from the transit—attempts hampered by the “black drop” effect, when Venus’s edges smear those of the Sun’s, making accurate observation impossible. Popularly attributed to the compounding roles of atmosphere and telescopic imperfections, the effect is a case study in the unreliability of images. Science, in other words, must contend with the capacities and limits of its chosen technologies; and from their constant refining, the voiceover proposes, we are given an “illegitimate child” like cinema. Starling could be called, in turn, the bastard son of historiography. The artist’s associational, “‘hypertextual’ assemblage” often yields depth and indulgence in equal measure, but in the case of Black Drop, his method finds kinship with science’s aberrations.