Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

July 10, 2024 – Review

Gabriel Chaile’s “Los jóvenes olvidaron sus canciones o Tierra de Fuego”

Filipa Ramos

Humans became human by representing themselves and others. By painting images on cave walls of animals that mimicked those they chased, early humans produced the imaginaries and traditions that define us as a species. With their drawings, they invented past and future and connected memory to desire, remembrance to anticipation, trauma to anxiety. The images on those walls might be still, but the stories they told were in motion, animated by the light cast by flickering fires. As such, it could be said that the history of cinema predates written history. Cinema emerged from the animals whose images, engraved in their own blood and hair, expressed motion through time and space, and moved their audiences.

This awareness of the archaic nature of cinema, and its relationship to nature, is at the base of Gabriel Chaile’s memorable installation Selva Tucumana [Tucumán Jungle] (2024), which signals an important change in his artistic vocabulary away from the large-scale adobe figures for which he is best known. Born in San Miguel de Tucumán in 1985, the Lisbon-based artist has often sought inspiration in land and kin. His characteristic anthropomorphic sculptures—whose aesthetics echo the precolonial creations of his birthplace—are both private and public. Connected to …

June 17, 2024 – Review

“Patterns of (In)Security II”

Nina Chkareuli-Mdivani

Taking its name from Michel Houellebecq’s 2005 novel The Possibility of an Island, this artist-run space in Berlin’s Mitte neighborhood hosts the second iteration of a dual exhibition that hints at the possibility of establishing a space of refuge between divergent positions. Extending a collaboration that began in Tbilisi last year, Sabine Hornig and Tamuna Chabashvili seek to establish some common ground between idealism and pragmatism, collective and individual, order and freedom.

Hornig presents a sculpture and photograph engaging with the sustainability of democracy as it is accosted on all sides by populism, chauvinism, and realpolitik. Wahlkabine (2024) is a freestanding metal structure, the grids of which are patterned like bricks, inspired by Tbilisi balconies. In Georgia, these private-turned-public structures are markers of the turbulent 1990s, when citizens of a fledgling democracy were trying to carve out spaces for themselves in the new post-socialist reality. The architectural structure creates two small rooms that can only be entered from different sides.

Translating as “voting booth,” the sculpture observes you as you observe it. There are small mirrored tables in each of the divided sections, reminding the visitor of their personal responsibilities. In its evocation of the wall that once stood …

February 28, 2024 – Review

Tania Bruguera’s “Where Your Ideas Become Civic Actions (100 Hours Reading The Origins of Totalitarianism)”

Eugene Yiu Nam Cheung

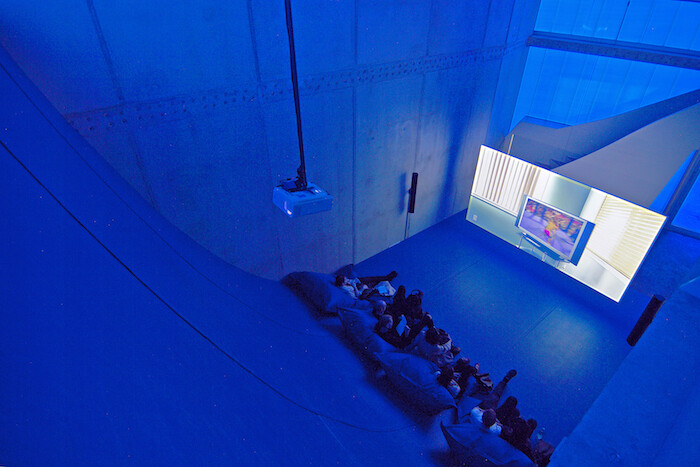

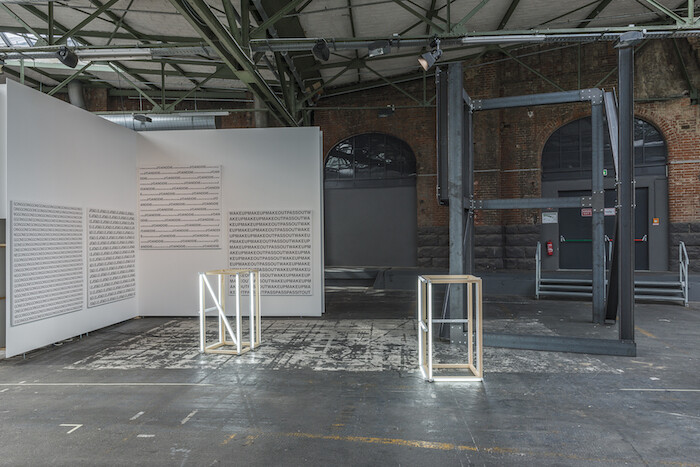

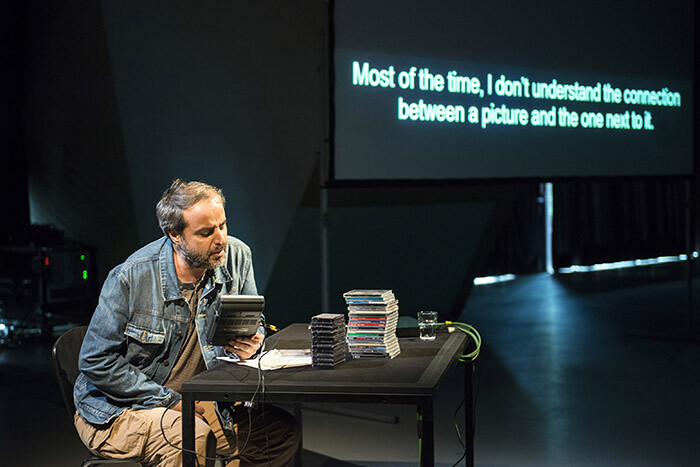

In Germany’s increasingly censorious intellectual climate, Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof staged the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera’s “Where Your Ideas Become Civic Actions (100 Hours Reading The Origins of Totalitarianism)” inside its main hall. This participatory public reading of—and discussion around—Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) was spread across four days, featuring the artist alongside writers such as Masha Gessen and Deborah Feldman, prominent artists in Berlin including Candice Breitz, and people from “the museum’s neighborhood.”

Speakers—mostly solo, sometimes in a trio, and even as a chorus—addressed the audience amid a spare scenography: a single rattan-upholstered rocking chair, illuminated from above by a beam of golden light. Hospital-gray bean bags and cardboard stools were strewn before it, stretching out towards the entrance of the museum and luring visitors into a collectivized consideration of “power and violence, plurality and morality, politics and truth.”

Microphones were connected to a sound system scattered haphazardly around the space, and synchronized with speakers outside the institution facing Invalidenstraße, a thoroughfare leading to Berlin’s central station, a few hundred meters away. Like the work’s title, Bruguera’s sonic gesture felt prescriptive—as if it were the artist’s duty to break Arendt out of the institution and onto the …

January 25, 2024 – Review

“As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories”

Olexii Kuchanskyi

Against a backdrop of constant territorial changes in the former Soviet countries and the ongoing war in Ukraine, “As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories” explores the “geopoetics of North Eurasia.” The term denotes heterogeneous, yet tightly interconnected, political and cultural contexts under oppressive regimes, ranging from the Russian Empire to contemporary Russian imperialism via Soviet colonialism. Framed in the handout by HKW’s director, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, as a way of “being and seeing the world through the prism of the Global East,” the show tries to avoid any “totalizing vision” in favor of multiple subjectivities and geographies.

To achieve this, the show’s curators—Cosmin Costinaș, Iaroslav Volovod, Nikolay Karabinovych, Saodat Ismailova, and Kimberly St. Julian-Varnon—have scattered the artworks across the museum in a way that foregrounds their discreteness, each piece separately lit and surrounded by empty space. Stories of colonialism, resistance, and artistic experimentation are encapsulated in these “monads,” yet the aversion to a “totalizing vision” extends to the bewildering absence of wall texts from the galleries (viewers hoping for context must flip through the handbook, which lacks a general plan of the show, to find a work description).

The exhibition’s main space is filled …

October 24, 2023 – Review

Coco Fusco’s “Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island”

JS Tennant

It comes as no surprise that “Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island” opens with documentation of Coco Fusco’s Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West (1992–94): her justly famous performance with Guillermo Gómez-Peña, staged at the moment the world was tussling over how best to commemorate, or denigrate, the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s so-called “discovery” of the Americas. A prime benefit of the Cuban-American artist’s first major retrospective—curated by Léon Kruijswijk and Anna Gritz—is to be able to trace the arc of suggestive continuities within her impressive thirty-year body of work.

In Two Undiscovered Amerindians, Fusco and Gómez-Peña toured the world in a cage where they were displayed as “natives” of a recently discovered Caribbean island. A subsequent film, The Couple in the Cage: A Guatinaui Odyssey (1993), captures this performance and reactions from the public, its footage intercut with a montage of real-life circus sideshows, world fairs, and racist “ethnographic” dioramas. Attendants, acting as ringmasters, invite passersby to interact with the couple, who speak no English. Bananas are fed to them through the bars; the “female” can be made to dance; five dollars grants a titillating fondle of the “male specimen’s” genitalia. The island’s name, Guatinau, would be pronounced, in …

October 16, 2023 – Review

Lin May Saeed’s “The Snow Falls Slowly in Paradise”

Jesi Khadivi

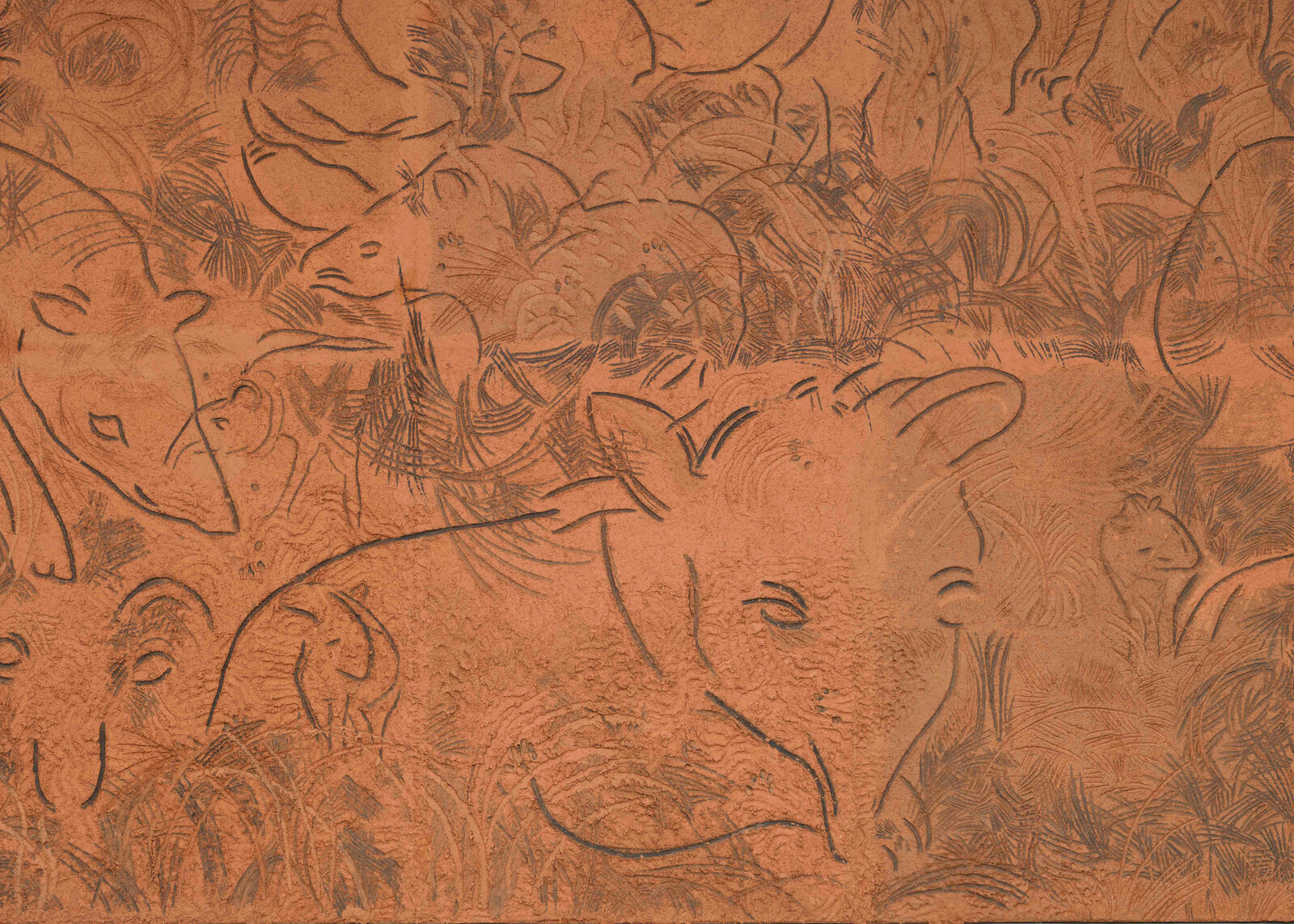

In What is Philosophy? (1991), Deleuze and Guattari write that “art is continually haunted by the animal.” Looking back through millennia of artistic production, we see representations of our beastly counterparts everywhere: as companions, deities, workers, or raw material. Likewise, John Berger has argued that “the parallelism of their similar/dissimilar lives allowed animals to provoke some of the first questions and offer answers.” Yet a life in common, and the reciprocal gaze that humans and animals once shared, was lost in the West with the development of nineteenth-century capitalism. The practice of German-Iraqi artist Lin May Saeed brings the image of the animal from the periphery back to the center.

Saeed devoted her life, sadly cut short by brain cancer at the age of fifty last month, to the cause of animal liberation. Her work avoids agit-prop depictions of animal suffering and instead draws on myths, stories, and fables so that we might “imagine a kind of time travel with a focus on the human-animal relationship” and “think about our common future” by looking at the past. “The Snow Falls Slowly in Paradise,” in which Styrofoam sculptures and reliefs, figurative wall works, drawings, and videos are shown alongside animal sculptures …

October 11, 2023 – Review

Jota Mombaça’s “A CERTAIN DEATH/THE SWAMP”

Harry Burke

In the final chapter of her 2016 book In the Wake, Christina Sharpe meditates on the weather, which for her signifies the “pervasive climate” of antiblackness in the modern world. Her argument is shaped by the insight that “new modes of writing, new modes of making-sensible” are needed to account for the quotidian violence of the colonial present. Jota Mombaça’s “A CERTAIN DEATH/THE SWAMP” builds on these contentions through a series of artworks that address the weather and, when viewed together, make up an atmosphere.

While preparing for the show, Mombaça researched the disastrous flash floods that struck western Germany and neighboring countries in 2021, as well as Berlin’s origins as swampland, drained in the 1700s. What would it mean, the artist asked herself, for cities to turn back into swamps? until the last morning (2023), made in collaboration with Anti Ribeiro, Darwin Marinho, and Luana Peixe, is her oblique answer to this. The looping, fourteen-minute video studies the mangroves and marshlands of Pará in her native Brazil. Its long, pensive shots of clouds recall John Constable’s cloud studies of the 1820s. For the Romantic painter, clouds exteriorized emotions and symbolized modernity’s scientific advances. To today’s eye, they also refract …

July 19, 2023 – Review

Aziz Hazara’s “No Dress Code”

Edwin Nasr

“How then can we clean centuries’ worth of waste?” asks Françoise Vergès, reflecting on the devastation wrought by imperial conquests in the Global South. The question hangs over “No Dress Code,” artist Aziz Hazara’s affronting solo exhibition at Berlin’s PSM Gallery, which reflects upon the US military occupation of his native Afghanistan through the prism of trash.

Speakers housed in four modified, bright yellow–plastic jerrycans play soundscapes recorded by the artist over the past decade across Kabul. The title of this sound installation, Bushka Bazi (2023), is the Afghani name for these containers; together with the soundscapes, they conjure a distinct sense of place, but also of context. Introduced to the country through international aid cargos, they have been put to numerous uses since—from water carriers in peri-urban areas suffering from poor infrastructure to petrol-filled explosive devices used by the Taliban.

I am looking for you like a drone, my love (2021–22) is a large-scale photograph of colossal heaps of discarded material, sweepingly installed in a panoramic layout so as to cover the walls of the gallery’s central space. At first glance indistinguishable from the type of imagery disseminated by climate advocates to draw attention to environmental degradation, the …

July 14, 2023 – Review

“O Quilombismo”

Jesi Khadivi

The reopening of Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt was marked by three days of performances, concerts, lectures, readings, rituals, and blessings under the banner “Acts of Opening Again: A Choreography of Conviviality.” Those familiar with incoming director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung’s program at Savvy Contemporary, which he founded in 2009 and quickly established as a forum for deliberation, experimentation, and sociability, will recognize a continuation of its ethos of conviviality and hospitality as an integral aspect of institution-building. Yet how might such values transition to the larger scale of a bureaucratic German institution, which operates according to different metrics than more fluidly structured art spaces? How does a curatorial stance of cultivating intimate spaces within institutions ultimately expand the channels through which we can engage with art and with each other? How does an invisible curatorial material like intimacy manifest itself within an exhibition? And finally, how might such a politics of conviviality be enacted within what Ndikung has referred to as “the belly of the beast”? These questions pervaded my thinking about “O Quilombismo,” a show whose concept and content are entirely entangled with the act of thinking how to “institute.”

The inaugural exhibition in HKW’s new program …

June 27, 2023 – Review

María Magdalena Campos-Pons’s “Liminal Circularity”

Kimberly Bradley

According to Yoruba myth, only one of the seventeen deities sent by the supreme being Olodumare to populate the earth could do so. After her sixteen male co-divinities failed, Oshun, the goddess of water, fertility, love, and protection, used her sweet waters to revive Earth and create its creatures. At Galerie Barbara Thumm, María Magdalena Campos-Pons pays homage to Oshun with the vibrant gouache triptych Untitled (2021). The artist was born in Cuba in 1959, the year the Cuban Revolution succeeded; Oshun is an important figure in Santeria practices, integrated into Latin American and Caribbean belief systems via the slave trade. Here, a female figure’s outstretched arms cradle a burst of dark-brown blooms, framed by yellow petals—a stylized sunflower spilling over three framed pieces. The sunflower is a symbol of Oshun, and the piece, an invocation of sorts, exudes generosity, abundance, and hope.

Campos-Pons—whose ancestry is Yoruba and Chinese as well as Cuban—is experiencing her own burst of recognition. She’s been known, shown, and studied since the 1980s, but institutional exhibitions in both the Global North and Global South have since 2020 arrived in a rush like the flowing waters she often depicts in her multimedia work. While this reflects …

May 19, 2023 – Review

“Retrotopia: Design for Socialist Spaces”

Sierra Komar

To turn left upon entering the darkened exhibition hall of “Retrotopia: Design for Socialist Spaces” is to encounter a motley, utterly heterogeneous collection of objects ranging from the decorative to the domestic to the medical. Nestled against one wall is Cosmic Fantasy (1965): an experimental public sculpture work by Lithuanian artist Algimantas Stoškus consisting of luminescent slabs of stained glass arranged, Tetris-like, on a series of suspended geometrical forms. Adjacent to this is a mint condition Saturnas vacuum cleaner—the ultimate kitschy fusion of lofty, celestial aspirations and household banality—complete with orbiting moon wheels and ring. In a vitrine just opposite the Saturnas is the least recognizable item of the group: a tubular, vaguely biomorphic form that appears to be woven out of some sort of textile. This, it turns out, is one of the first vascular prostheses ever made: a specific model of artificial aorta manufactured in 1960s Lithuania using re-engineered German ribbon-weaving machines. Selected by Lithuanian curator Karolina Jakaitė, this eclectic assemblage of objects and artworks (along with contributions from other Lithuanian creators like sculptor Teodoras Kazimieras Valaitis and architect Vytautas Edmundas Čekanauskas) is one of eleven unique “capsules” that comprise the collaboratively curated “Retrotopia.” In its simultaneous diversity …

April 5, 2023 – Review

73rd Berlin International Film Festival, “Forum Expanded”

Asia Bazdyrieva

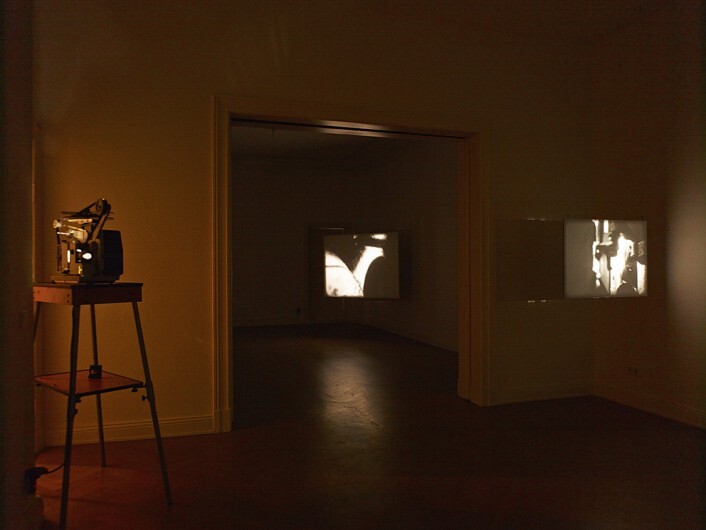

The “Forum Expanded” section of the Berlinale, an assemblage of exhibitions distributed across three venues and any number of screens, charts the points at which cinema meets the visual arts. This year’s edition, titled “An Atypical Orbit,” aimed to set in motion “fluctuating proximities—political and personal legacies which often lie in shambles” and to “challenge the status quo through exhibiting works that redefine cinema.” In attempting to solve two problems—to host a platform for political articulation, and to critically engage with moving images and media as such—the Forum Expanded faced a conundrum: its archival and historiographic approach, as well as the aesthetic and political emphases in the overall selection of works and conversations, induced a certain lethargy: a sense of being unwilling or unable to respond to those current emergencies which do not yet have established narratives.

In Betonhalle’s entrance corridor, Tenzin Phuntsog’s Dreams (2022) set up the exhibition’s dream-like ambience. The work portrays a sleeping couple— immigrants from Tibet to the US—floating in space against a quiet, blueish monochrome background. The pair reappear in a two-channel video, Pala Amala (2022), posing silently in nondescript settings. These large-screen, meditative works sat in contrast to the small, phone-like screens which …

March 22, 2023 – Review

Martin Wong’s “Malicious Mischief”

Mitch Speed

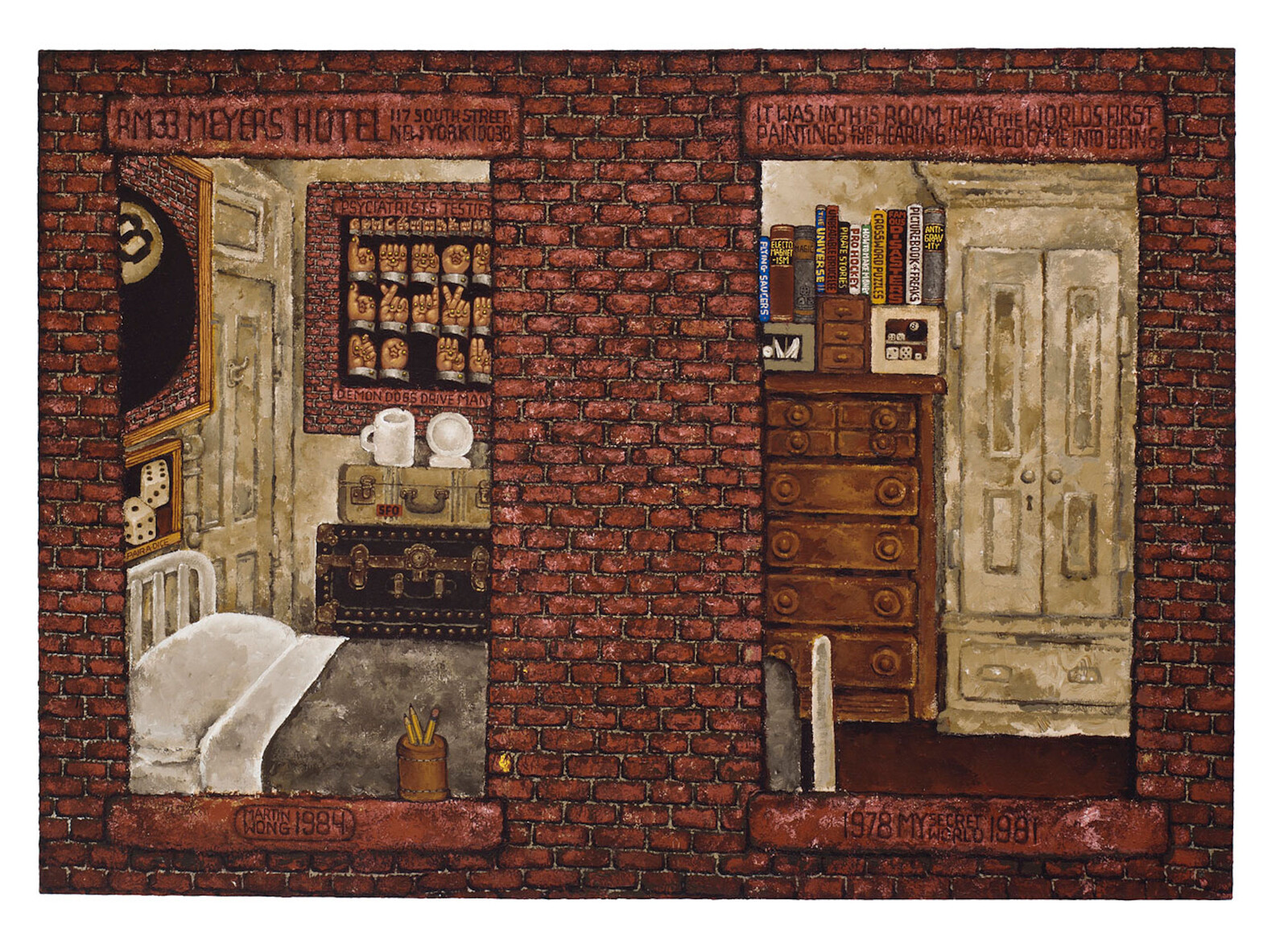

In a 1988 catalog essay, the poet and critic John Yau sketched out the social dimension of Martin Wong’s painting and sculpture. A self-styled “representative of an economically oppressed urban class consisting largely of Blacks, Hispanics and Asians,” the American artist had been snubbed by curators and critics. A quarter-century after Wong’s death, this injustice has been corrected, and this Berlin retrospective of his antic, steamy, humane, and superlatively accessible take on Chinatown San Francisco and New York, from the 1970s to the ’90s, has been lauded. But there’s an anxiety buried in this enthusiasm. In depicting a disappeared America, Wong’s retrospective holds a mirror to the lost world which surrounds KW itself.

“Even now,” Wong wrote in a hand-calligraphed 1986 press release, “it’s like the moment in these paintings never existed.” His home cities—his subject—were being gentrified to oblivion. In 1984, New York Magazine wrote of Wong’s downtown Manhattan: “nowhere have the tensions and dramas of [gentrification] been more starkly displayed.” Set aside the differences between the cities and eras, and the same has recently been true of Mitte, the Berlin district in which KW is situated.

Nocturne at Ridge Street and Stanton (1987) shows an unpeopled but warm …

October 14, 2022 – Review

“Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer”

Anne Finger

In 2015, the disabled American writer Kenny Fries gave a reading as part of the program for “Homosexuality_ies,” an exhibition jointly sponsored by the Deutsches Historisches Museum and the Schwules Museum. During it, he posed a question: Where, he asked, was disability in this wide-ranging exhibit? Why had access for disabled people been ignored? The response to that challenge is “Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer” at the Schwules Museum. Co-curated by Fries, Birgit Bosold, and Kate Brehme, it is one of the first international exhibitions to explore the artistic, political, and historical links between queerness and disability. It presents disability as sexy, provocative, tough, and a source of artistic strength—not a black hole of suffering and blankness.

Access is at the heart of the show. Seated in my wheelchair, I could actually experience the art. Nearly always when I enter a museum (sometimes after having been assured that a show is “completely accessible”) I am able to see only a fraction of what is on display, and I am left wondering: “What does that wall text, too high for me to read, say?” I might be able see diaries, letters, magazines in a display case, but the height …

June 15, 2022 – Review

12th Berlin Biennale, “Still Present!”

Jesi Khadivi

As curator of the twelfth edition of the Berlin Biennale, Kader Attia continues his ongoing engagement with notions of injury and repair. There is precedent for this in his own artistic practice: the sprawling installation The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures (2012) staged reconstructed artifacts from ethnological collections that clearly reveal their stitching and staples, drawing a contrast with Western approaches to restoration that conceal an object’s damage and thereby silence the many stories it might tell. In the series “Repaired Broken Mirror” (2013–21), Attia sutured nondescript fractured mirrors with crude materials like staples or copper wire, a gesture of repair which appeared no less brutal than the act of breaking. The visible scars and reflective surface feel emblematic of this exhibition’s aspirations to hold a mirror to the legacies of colonialism and imperialism, sweeping environmental destruction, racism, sexism, and forced displacement due to war and climate change—and to propose ways forward.

Through works by 82 artists and collectives displayed across six venues, Attia endeavors to foster spaces of “collective speech and reflection” that respond to the accumulated, unhealed wounds that have been rendered invisible by discourses of expansionism, algorithmic governance, and 24/7 capitalism. Working against the universalist claims of …

April 19, 2022 – Review

Rabih Mroué’s “Under the Carpet”

Jayne Wilkinson

“One of the main weapons is the image itself.” So proclaims Rabih Mroué in his 2018 lecture-performance Sand in the Eyes. With trademark brevity, his statement articulates the complex recurring strategies—analyzing images as weapons, conflating theatricality with war, reading revolutions through pixels—that underlie Mroué’s multidisciplinary projects as a visual artist, actor, playwright, and director. This mid-career survey, surprisingly also his first solo exhibition in Berlin, brings together two decades of work and, incredibly, eight new commissions produced largely during the pandemic.

In design and execution, its ambitions are staggering. A non-linear constellation of video projections, installations, collages, and archival material are structured around a two-story vertical video that can be seen from all corners of the exhibition’s two floors. With so many video and audio works, the sound bleeds (a plinky xylophone suggestive of a film score’s anxious denouement, punctuations of gunfire and explosions that arrive unexpectedly, the noisy insistence of a film projector) effectively recall the sonic chaos of war while still creating an integrated audio environment.

The imposing central work, Images Mon Amour (2021), loops through imagery culled from Lebanese newspapers, with the benday dots of analog print enlarged and visible. Weaponry, …

April 15, 2022 – Review

Zoe Leonard’s “A View from the Levee”

Jesi Khadivi

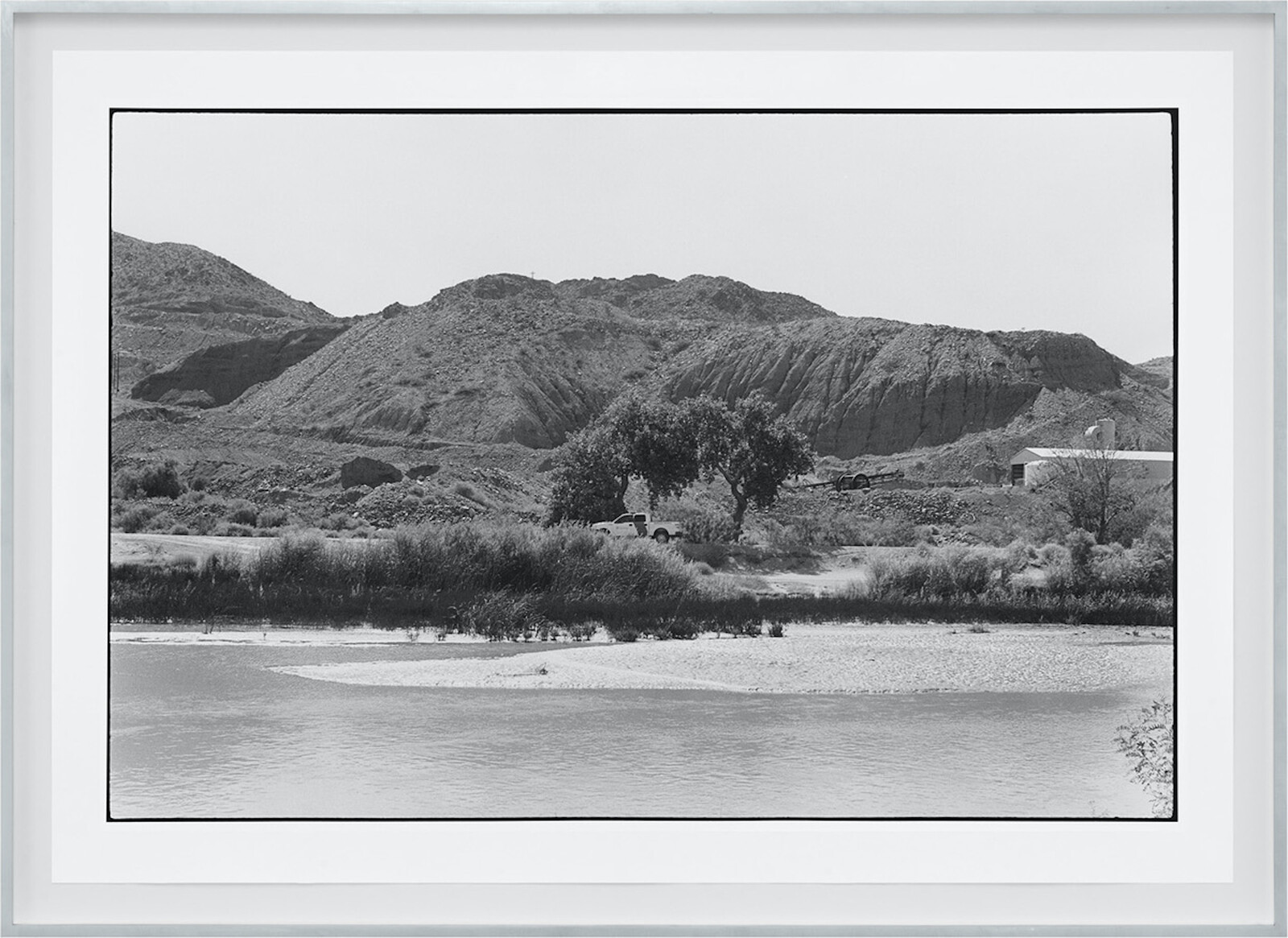

Art historian Darby English describes humans’ relationship to the natural world as “an interchange of flow and force,” a phrase that also evokes the way geological forces are harnessed to mark political boundaries. Zoe Leonard’s epic photographic work Al río / To the River, created between 2016 and 2022, comprises approximately 500 black-and-white and 50 color photographs of the river that marks the border between the United States of America and Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Called the Rio Grande by Americans and the Rio Bravo by Mexicans, the numerous violent modifications the river has undergone testify to this entanglement of flow and force: over the last century engineers have forcibly straightened and shortened its meandering natural course by nearly 67 miles, lining its base in concrete so that it may never shift its channel again. The river’s edge is alternately home to cities, towns, border patrols and facilities, grazing animals, and open expanses. In some places it flows wide and mighty, while in others no water runs through, and its cement embankments form what scholar C. J. Alvarez describes as “a massive trapezoidal canvas for graffiti.”

Before Leonard zooms out to capture this interchange, she zooms in. Upon entering “A View …

October 8, 2021 – Review

“The Cool and the Cold”

Ryan Ruby

I am standing in front of two full-length portraits, each just over 200 centimeters tall. The one on the left is a gray-scale screen print; in it, a man in a billowy shirt with a popped collar, jeans, and cowboy boots has emerged from the void to draw a revolver from the holster at his hip, which he points at the viewer. The one on the right is painted in thick, dark oils; it shows a man in a black three-piece suit and polka dot tie, his hands in his trouser pockets, standing in his study, before wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and a desk covered in a red, tasseled table cloth, on which the viewer can make out two candlesticks and a set of miscellaneous papers. The subject of the first painting is Elvis Presley. The subject of the second: Vladimir Lenin.

These two portraits—Andy Warhol’s Elvis Presley (Single Elvis) (1964) and Dmitriy Nalbandyan’s Lenin (1980–82) respectively—flank the entrance of “The Cool and the Cold: Painting in the USA and the USSR 1960-1990,” a selection of over 125 pieces from the collection of the late chocolate manufacturer and art historian Peter Ludwig and his wife Irene, now on view at the Gropius …

April 27, 2021 – Review

“A Fire in My Belly”

Alan Murrin

This show of 47 works by 36 artists—41 drawn from Julia Stoschek’s collection, augmented by six loans—explores the effects of violence, physical and psychological, on the body and the body politic. The earliest work on display is Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach’s Capri (1911), an oil painting showing a sunset burning out over a darkening coastline; the most recent is Anne Imhof’s Untitled (Wave) (2021), a thirty-minute video wherein a lone figure stands on a shoreline, beating back the oncoming tide with a whip. The show is filled with careful pairings, its emotional register ranging from despair to hope, from the abject to the sublime. It takes its title from David Wojnarowicz’s 1986–87 montage of spinning eyeballs and sewn flesh, mummified corpses and ants crawling over a figurine of the crucified Jesus; on the opposite wall hangs Zoe Leonard’s Untitled Aerial (1998/2008), a photograph of a vast landscape with a river wending through it like a strip of silver ribbon. The two sit in silent communion, the naked landscape a counterbalance to the corporeal concerns of Wojnarowicz’s work. As is so often the case with this show, the wound inflicted by one piece is salved by the next.

On entering the space, …

September 29, 2020 – Review

“Studio Berlin”

Alan Murrin

“Morgen ist die Frage”—tomorrow is the question—reads the banner by Rirkrit Tiravanija which swathes the top floor of Berghain’s façade. The statement seems antithetical to the philosophy of the most famous techno club in the world. Before lockdown began and ravers were forced to find their fun at illegal parties in the parks of Berlin and the forests of Brandenburg, Berghain was where you went to forget about tomorrow. If you could brave the lengthy queue and possible rejection by the club’s notoriously mercurial door staff, days of hedonism lay ahead. But for now, the 3,500-square-metre venue, first a power plant and then a nightclub, has become an exhibition space.

When Covid-19 forced clubs and galleries to close in March, Berghain’s owners approached Karen and Christian Boros about mounting an exhibition to provide a platform for artists who live and work in the city. Funded by a 250,000 euro grant from the Berlin Senate, the show does not feature work from the Boros Collection—housed in a World War Two bunker in central Berlin that was itself once a techno club that hosted fetish parties—but they and Juliet Kothe, director of the Boros Foundation, are listed as co-organizers. As an overarching …

September 14, 2020 – Review

11th Berlin Biennale, “The Crack Begins Within”

Jörg Heiser

“Here, the concept of ownership is abstracted until it disappears.” This is the official slogan of ExRotaprint: a former print-press factory collectively run as a mix of art studios, workshops, and community initiatives in Wedding, north Berlin, and one of four venues for the 11th Berlin Biennale. For about a year leading up to the exhibition’s opening, the curatorial team—María Berríos, Renata Cervetto, Lisette Lagnado, and Agustín Pérez Rubio—hosted a series of readings, screenings, workshops, and performances here which set the tone. Though interrupted in March by the pandemic that prompted the show’s postponement from June to September, the approach could be summarized as: “Here, the concept of curatorial heroics is abstracted until it disappears.”

Which is to say: this Biennale foregrounds work that addresses socio-political traumas past and present, and the effects of violence inflicted on the marginalized. (This is also how I understand the title “The Crack Begins Within,” borrowed from a line by poet Iman Mersal.) Despite curatorial texts that occasionally wax a little too poetic, the team circumvents the usual pitfalls of self-congratulatory gesturing and puffed-up wokeness that reduce artists and their works to issue-tokens or neo-ethnographic trophies. The works at ExRotaprint point towards the basso …

June 16, 2020 – Review

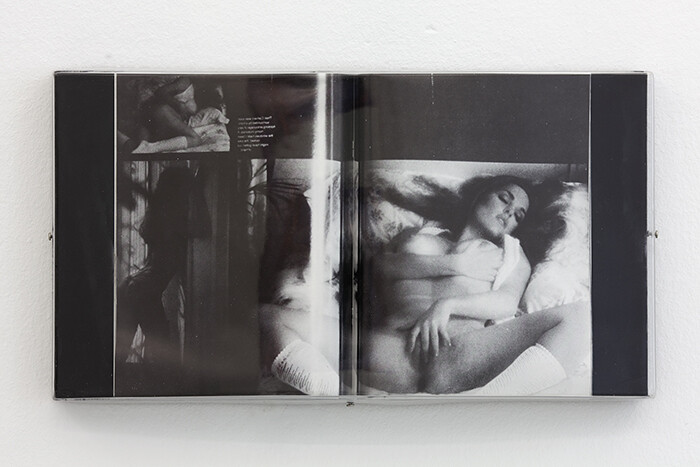

Erica Baum’s “A Method of a Cloak”

Martin Herbert

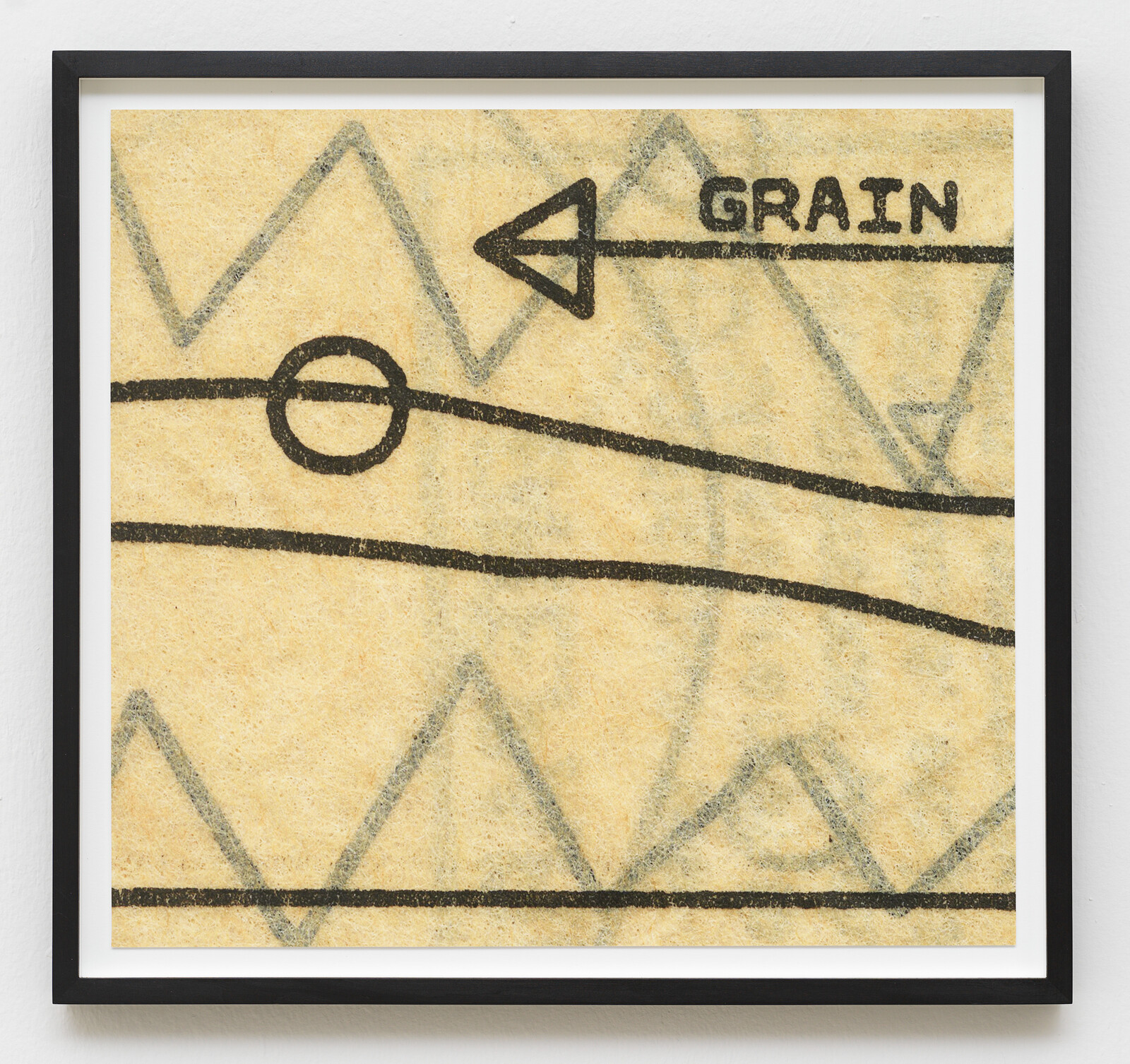

Since the mid-1990s, Erica Baum has been coaxing a fragmented poetry from the unlikeliest places, quarantining found snippets of text that never aspired to great significance and dilating both their scale and their associative potential. Early on, the New York-based artist moved her camera close to half-erased classroom chalkboards (“Blackboards,” 1994–96), releasing details of equations, diagrams, and language from the burden of signifying and making them simultaneously abstract and allusive (e.g. the slyly reflexive smidgen of chalked text “TO DEPTH”). Since then, Baum has focused primarily on worldly printed matter; in “The Naked Eye” (2008—ongoing) she took stipple-edged trade paperbacks from the sixties and seventies and photographed them side on, scraps of illustration and text peeking chancily through tightly formalized verticals. For all her scrambling, though, the conceptual dynamic feels legible. A second-wave wrangler of Pictures Generation insights, Baum aims to illuminate a covert, sometimes incriminating largesse in the discarded and to purposefully collapse together not only high and low, as we once called them, but visual and verbal, banal diagram and highfalutin abstraction, the Apollonian and the edgeless.

So she has a furrow and she’s ploughing it diligently, or, to extend the spatial metaphor, Baum …

March 22, 2020 – Review

Leila Hekmat’s “CROCOPAZZO!”

Alan Murrin

Individualistic societies are driven by the belief that happiness is to be found by accessing our “best” and most “authentic” selves, and that this can be achieved by spending money. Therapeutic practices ranging from the seemingly benign to the dangerously experimental enforce the psychological norms that uphold that system. But what happens if we relinquish control of our drives and desires, rather than trying to make them cohere? And what happens if that process is presented as entertainment? Leila Hekmat’s carnivalesque exhibition—prematurely closed as people are forced into their houses by Covid-19—conducts a dangerous experiment of its own: can a family induce psychosis in one member by forcing that individual to bear the weight of their collective dysfunction?

Hekmat writes, directs, and creates costumes for highly aestheticized experimental theatre pieces performed in intimate spaces. Her previous exhibition, “I Was Not Invited” (2018, co-presented by Bortolozzi and Duddell’s Hong Kong), took inspiration from Franz Schubert’s Winterreisse (1828), the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé, and Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse (1977), and—like this show—found humor in suffering. “CROCOPAZZO!” is split across three rooms, the first filled with eight mannequins posed as if interrupted mid-dialogue. One figure raises its palms in an attitude of …

March 17, 2020 – Review

70th Berlin International Film Festival, “Forum Expanded”

Leo Goldsmith

Finding space for exhibitions within the sprawling architecture of a major film festival is a tricky affair. Berlinale’s packed schedule and multiple sidebars do not easily accommodate excursions to far-flung locations to see an assemblage of works of different lengths and modes of reception. Trickier still is the act of importing into a film festival context those discourses that are currently trending in the art world—at least in any way that doesn’t seem like a cynical bid for political relevancy. This year’s edition visibly wrestled with these problems, hosting three exhibitions that struggled to find coherence within the format of the larger festival—or to break free of it.

For the last 15 editions, Berlinale has housed exhibition work under the aegis of Forum Expanded—itself a subsection of the International Forum for New Cinema, which has been organized by Arsenal–Institute for Film and Video Art since 1971. Taking as its remit “experimental film and video art for both cinema and exhibition contexts,” Forum Expanded presents a dozen or so theatrically presented film programs, panels, and exhibition works, which offers a certain contrast with the gala premieres and red-carpet photo-ops elsewhere in the festival.

This year’s edition of Forum Expanded featured three …

June 14, 2019 – Review

Sol Calero’s “Archivos Olvidados”

Sofia Lemos

For her first exhibition at Berlin gallery ChertLüdde, Sol Calero transformed the typical German altbau into a luminous and colorful family home inspired by the artist’s grandmother’s farmhouse in Los Llanos, Venezuela, a grassland plain south of Caracas, where Calero and her cousins spent the summer months.

In Jesús Martín-Barbero’s seminal study of the role of media in the formation of national cultures in Latin America, social memory emerges as vivid mise-en-scène where popular iconography and labor struggles are ambiguously combined, creating a new social sensibility predicated on access to forms of expression. Experiencing and expressing the world becomes a matter of public fiction, wherein moments of systemic muting and glossing over the collective archive grow deeply entwined with class imaginaries. In this recurring scenario, oral histories, with their warranted omissions and excesses, reclaim an important effort in tracing personal and social routes. For Calero, the turn from personal archive to social space lays the foundation for “Archivos Olvidados” [Forgotten Archives], a thoughtful tribute to the fluidity of memory, childhood anxieties, and the artist’s late grandmother, the painter Luisa Hernandez, lovingly referred to as “Abuli.”

As a widow, Hernandez raised six children, studied fine art in Caracas, and returned to Los Llanos …

February 26, 2019 – Review

Daniel Pflumm

Kirsty Bell

A cloud of stale smoke still hangs in the air the day after the opening of Daniel Pflumm’s exhibition at Galerie Neu, a throwback to another time—15 years ago, perhaps, when Pflumm had his last show at his hometown gallery and smoking indoors was still the norm. This new exhibition not only recalls the 1990s techno scene from which Pflumm’s work emerged, but also an ambivalence toward the art-world context in which it came to find itself. The commercial gallery trappings have been removed: reception desk and gallery assistant replaced by a shiny metal clothes rack with a sign, red on white, reading “SPECIAL” and two mirrors framed on the wall. Inside, the gallery has been transformed into an intimate cinematheque, with GDR-era folding chairs and portable metal ashtrays. Two dark windows offering clandestine views back into the reception reveal those mirrors to be two-way glass. Pflumm’s two new video works have all the harsh relentlessness of his early ones: as sharply edited as they are critical.

While in Pflumm’s previous videos, content was usually derived from, and shown on, a TV screen, the main work here, Hallo TV – FFM (2019), is a luxuriously large projection in the cinema/gallery that …

February 4, 2019 – Review

Raphaela Vogel’s "Son of a Witch"

Aoife Rosenmeyer

Raphaela Vogel turns her chaotic, insistent, and reflexive gaze on religion in her video installation “Son of a Witch,” presented at the Berlinische Galerie as part of the 10th anniversary celebration of the Videoart at Midnight Festival. After walking through a portal delicately molded from white plastic and featuring dragons and a phoenix, viewers enter a dark gallery spanned by two huge metal frames used in agricultural tunnels. These nested structures resemble a complex ribcage, yet the space has the feel of a church. Viewers are drawn to Sequenz (2018), a video projected on a large screen at the far end, where the church’s apse would be. Spinning, round motifs fill the screen: for much of the video, the artist films herself lying in a circular bed, staring into the camera. Both watching and watched, she lures the camera closer before presenting her sweatpants-clad bottom and slapping it with her hands. On the soundtrack, a classical motif is picked out slowly on a keyboard. There is a choral piece by Benjamin Britten, a brief blast of Low Deep T singing “Please don’t / stay with me / go home”—then the screen goes blank.

The architecture and symbols of most places of …

January 31, 2019 – Review

“The New Alphabet — Opening Days”

Nick Currie

A city with an institution like the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW)—Berlin’s House of World Cultures, a cantilevered cockle shell sitting on the Spree River beside the chancellery buildings that fund it—is a happy city indeed, for it can boast a progressive intellectual hub, a cultural engine spitting with vigor and restless curiosity. HKW is a bulwark against commercial logic, the surging tides of populism, and the threat of Western “endarkenment.” Massive subsidy is required, of course. Offered here by the Kulturstiftung des Bundes, the German state culture fund, that subsidy is neutral enough to allow the institution’s directors to strike the right balance between affirmation and contestation, observation and critique.

Events like “The New Alphabet — Opening Days,” a four-day launch for a program of events that will run for the next two years, exploring cultural, political, and critical approaches to alphabets and code, do not play to empty rooms. Berlin supplies an audience of culturally active people filled with enthusiasm for questions that might strike the citizens of more pragmatic, phlegmatic towns as heavy and pretentious. The blurb for “The New Alphabet” begins with three such questions: “Is it possible to imagine an overabundance of multifarious fields of …

July 5, 2018 – Review

Louise Bourgeois’s "The Empty House"

Kimberly Bradley

It’s intimidating to review the work of an artist the stature of Louise Bourgeois, about whom so much has been written, to whom so much has been ascribed. Bourgeois’s life spanned nearly the entire twentieth century and helped redefine what a (feminist) artistic practice can be, how art can intertwine with life. Her legacy is outsized, but Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon—a nonprofit art space in a GDR-era structure, run since 2007 by artist Nina Pohl—has put together a portrait of Bourgeois’s late work that is accessible and intimate.

The pavilion’s main space, an octagonal room with floor-to-ceiling windows, hosts a single work: one of the “cells” that Bourgeois began making in the early 1990s. Peaux de Lapins, Chiffons Ferrailles a Vendre [Rabbit skins, Scrap Rags for Sale] (2006) is an oval metal cage in the room’s center containing other sculptures: two humanoid figures, hand-sewn in dark fabric, hang upside-down like voodoo dolls from an apparatus attached to the cell’s ceiling. Also suspended are textile sacks, mostly in shades of beige and cream (one is hot pink), arranged in flock-like groups. A thin stack of white marble stones ascends from the cell’s wood floor—atop this elegantly curved “spine” hangs an old-fashioned fur headband. …

June 11, 2018 – Review

10th Berlin Biennale, “We Don’t Need Another Hero”

Patrick J. Reed

During the press conference for the 10th Berlin Biennale, henceforth snappily referred to as “BBX,” the attendees were given the opportunity to contemplate Hakuin Ekaku’s lesser-known koan—“what is the sound of one person’s inappropriately timed clapping?”

The lone applauder, whose ruckus died away with all the glory afforded a deflating balloon, was prompted by Yvette Mutumba’s statement that, unlike her fellow curatorial team members, who were speaking English, she would be making her opening comments in German. Respect for a host country’s mother tongue notwithstanding, the clapping was a blunder considering the strong international representation in the room and the curators’ refusal “to be seduced by unyielding knowledge systems and historical narratives that contribute to the creation of toxic subjectivities.” Language, of course, is one such system.

For curator Gabi Ngcobo, BBX is entrenched in a war against oppression—and, as the abovementioned faux pas confirms, there are landmines everywhere. It is therefore unsurprising that the accompanying exhibition texts read as though written with an awareness that each word is potentially lethal to their curatorial cause. The authorial challenge was doubtless intensified by the biennale’s sweeping thesis: to ignite “a conversation with artists and contributors who think and act beyond art as they …

May 2, 2018 – Review

Gallery Weekend Berlin

Filipa Ramos

There are occasions in which the multifaceted shape of time becomes obvious. Occasions in which the concentration of similar initiatives, aimed at similar audiences and presenting similar outcomes, attest to the different moments in which organizations, individuals, and their mentalities are situated: how, despite coexisting simultaneously, collective mindsets aren’t contemporary to one another. Aimed at showing trendsetting cultural production and hosted in such a temporally dysfunctional city as Berlin—located in a permanent identity crisis between its haunting past and its daunting ahistorical future—the Gallery Weekend provides a good example of the heterogeneous configuration of this non-time called the present and how art participates in it. The present seems to be constituted by retrospective and anticipatory instances and institutions: individuals, objects, and imaginaries that live in parallel timeframes, either looking back or forward.

Sometimes, these temporal gaps are so large that different centuries span across the more than 50 exhibitions that opened during the Gallery Weekend. While some address the events and concerns that shaped the twentieth century, others look ahead, imagining the future. The moving image-based shows of two North American artists—Kara Walker and Ian Cheng, presented respectively at Sprüth Magers gallery and at the Berlin venue of the Julia Stoschek …

February 9, 2018 – Review

Transmediale, "face value"

Patrick J. Reed

To my left the casual love of mismatched hearts is expiring. The American woman says, “you’re sad,” and the Frenchman nods. She tells him to calm down. It is breathtakingly awkward. They resign themselves to stillness until a grinding electronic drone heralds their graceless end. She makes a break for the cash bar, and he, with less determination, joins the nearest crowd. He stares with them in solidarity at a webcam feed showing empty winter highways projected large, and finds solace.

This is transmediale, Berlin’s premier art/media/technology festival and sometimes boneyard for feckless romance. Over three decades it has showcased ideas by those working at the forefront of digital aesthetics and theory. Its mandate, by its own decree, “…aim(s) at fostering a critical understanding of contemporary culture and politics as saturated by media technologies.”

“Face value” is this year’s umbrella motif, and, like past themes, it is highly accommodating. Spanning five days, the lectures, exhibitions, conversations, and screenings investigate the power of surfaces, from the origins of “face value” as economics lingo to its application by racist ideologies within the mediasphere. With so many experiences to be had and shared here, both visitor and contributor are apt to become lost in the …

January 29, 2018 – Review

“That, Around Which The Universe Revolves: Chapter V: Berlin”

Mitch Speed

In the basement of a former Berlin crematorium, a small brass instrument sputters and hisses. The sculpture—Vartan Avakian’s Composition With A Recurring Sound (2016)—could be the baby cousin to a trumpet or saxophone. It is also the closest this group exhibition about rhythm gets to danceability. No surprise there. SAVVY is a space that emphasizes colloquy, meaning that its exhibitions and programs often seem less concerned with a central subject than that subject’s relation to a lived world. This exhibition concludes a program that extended into Berlin’s HAU theater and in 2016–2017 to Lagos, Düsseldorf, Harare, and Hamburg. It suggests an ad-hoc social nervous system, situating a willing viewer between the uncertainty of thinking and the affirmation of feeling.

The exhibition’s conceit is that artists can elucidate the unseen rhythms that structure life, while the rest of us—by implication—are bewitched by so many abstractions and constructs: work, finance, love… Not suffering from humility, this theme becomes modestly obliging in function: a discursive matrix interlinking the work. IQhiya—a collective of South African women artists—has modeled the possibility of questioning power through lines of free-association inquiry that one might liken to beats in social space. Monday (2017) is made from school desks covered …

January 17, 2018 – Review

"in search of characters…"

Patrick J. Reed

When the clock struck twelve in Berlin, “in search of characters…” transitioned from Galerie Neu’s final offering of 2017 into its first of the new year. Twenty-two works by fourteen artists comprise the exhibition exploring “questions of artistic identity/ies, authorship, and authority,” per the gallery press release. These perennial investigations take on various forms, but whether a painting or a minibar, all are aerated by two mischievous thoughts.

The gallery text conveniently articulates one: a rendition of the Duchampian “readymade” concept that, in 1914, crumbled the menhir of originality into the gravel upon which conceptualism has been driving in donuts ever since. At Galerie Neu, the most obvious benefactor of this tradition is Pubblicitá, pubblicitá, a 1988 advertisement designed for Philippe Thomas’s elusive faux company called “readymades belong to everyone ®.” Appearing as a poster and a postcard, it promotes the company’s initiative for a “total revision of authorial rights,” providing on-demand readymades ripe for inclusion among “all the best museums, galleries, and private collections.” Once in hand, the readymade product is in the custody of the buyer, who becomes its “sole and absolute author” (and art history’s exclusive canon becomes oversaturated with consumer anarchists). Sujet à discrétion (Subject to discretion) …

December 5, 2017 – Review

“The Undercover Economist”

Stefan Heidenreich

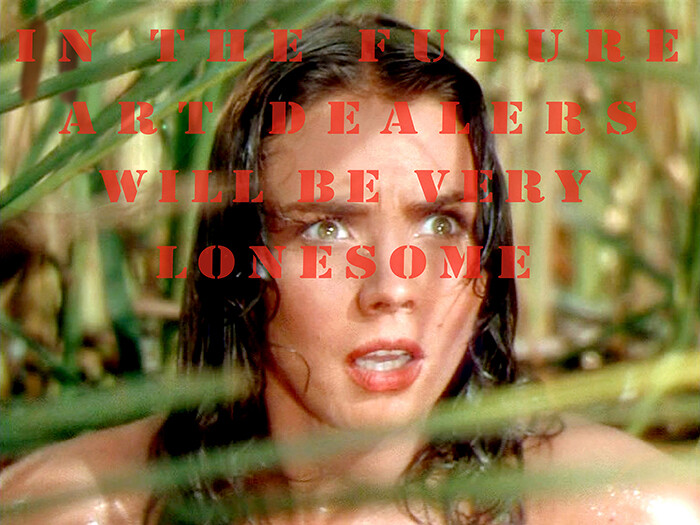

For some people, economy is mostly about money. But that is stupid: economy is actually about something else. Money is just the medium conventionally assigned to all tasks understood as economic. In the end, money is just a medium. For all those who firmly believe that the medium is the message, this might resolve the issue. In general I tend to count myself among these late McLuhanians, but when it comes to economy, I beg to disagree. Economy is not about money. It’s about distribution. And at this task, money performs worse and worse, as we know.

This misalignment hasn’t served the art world badly so far, at least for a small chunk of it. Maybe in a near future we will learn to read much of contemporary art’s output as an undercover service to this weird cult of liquidity.

The group show “The Undercover Economist” is centered around a sculpture by Liz Magor, titled Carton III (2006). Seen from the entrance of the gallery, it looks like a pile of old workers’ clothes. Shoes at the bottom, some trousers, a thick woollen pullover, and a heavy gray shirt on top, all neatly folded. Now, as if carried from one place to …

October 25, 2017 – Review

Katinka Bock’s “Smog”

Simone Menegoi

Katinka Bock compares works to words and exhibitions to texts. The analogy explains the relationship between the two aspects of the Franco-German artist’s work: the sculptures, silver prints, and occasional films, on the one hand, and the sophisticated displays that she creates out of them, whose value is greater than the sum of their parts, on the other. These correspond to two ways of reading Bock’s practice: to focus on the single work, with its delicate material qualities, or to embrace the whole, with its syntactic properties.

If Bock’s exhibitions are texts then “Smog,” her third solo show at Berlin’s Meyer Riegger, is particularly poetic. Two rooms are arranged as if they were two long sentences, rich in subordinate clauses and parentheses; sentences that could have been written by Marcel Proust, full of internal symmetries, of repetitions and variations, aimed at pursuing a nuance of perception or memory. The first room revolves around Grosse Liegende (2017), which is made out of several elements: a horizontal support (an old mattress coil topped by a glass pane), upon which the artist has placed the metal mold of a fish, a matte brown ceramic sculpture, and another ceramic sculpture with abraded blue enamel. The …

September 18, 2017 – Review

Art Berlin

Stefan Kobel

Can the German art market support four art fairs? The battle over market share is in full swing. Art Karlsruhe is a bit out of the game. Although it seems like a major event with more than 200 exhibitors, it can only cater to the country’s southwestern local audience due to its weak contemporary section. The two traditional strongholds of the market—Cologne and Berlin—are experiencing a major shake-up. The world’s oldest still-running fair for contemporary art, Art Cologne, faces a new competitor with Art Düsseldorf, set to open in November, less than an hour’s drive north. Set up by a company that had successfully run a low-level art fair in Cologne, the new fair has found support from MCH Group. The company owns Art Basel, which took a minority share in Art Düsseldorf as part of a strategy to boost its international activity in regional art fairs—with the option to take over the whole enterprise. So far the success seems somewhat dubious, not least because of the track record of Art Düsseldorf’s two founders, who in 2008 failed in establishing an international art fair in Cologne’s rival city under the name “dc.” So far only 9 galleries from Düsseldorf and …

June 29, 2017 – Review

“2 or 3 Tigers”

Ana Teixeira Pinto

Though at present the concept of “media” is almost wholly equated with communication technologies, throughout the modern period this notion extended beyond the technological field, to include aesthetic and spiritual registers. In the late nineteenth century, a medium was someone with the alleged ability to act as a psychic conduit or transmitter, able to capture cosmic vibrations like a human radio frequency receiver. In the broadest sense, the term “media” introduces the concept of a coded mode of materiality—as W. J. T. Mitchell noted, the very notion of mediation “already entails some mixture of sensory, perceptual, and semiotic elements.” Marshall McLuhan’s notion of media, for instance, includes any “material in unfixed form, or even formless material, such as electricity,” and Friedrich Kittler generalized the concept of media to include all “domains of cultural exchange.” The body, or more accurately the nervous system, is the locus of interaction, the site upon which different media intersect. By emphasizing the notion of light as a medium—albeit one without any content—McLuhan underscores its power to shape the forms of human perception and interaction, socially as well as spiritually.

In the exhibition “2 or 3 Tigers,” curated by Anselm Franke and Hyunjin Kim for the Haus …

May 31, 2017 – Review

Eva Kot’átková’s “Diary of a stomach”

Ana Ofak

“What have you eaten today?” a metallic voiceover inquires. The reply, uttered by a child, hesitantly, is “nothing.” Yet in the course of the transitory interrogation that unfolds in the middle of Eva Kot’átková’s most recent film Stomach of the world (2017), currently being shown by the Polyeco Contemporary Art Initiative at the Benaki Museum in Athens, and related to an exhibition currently on view at Berlin’s Meyer Riegger, nothing becomes plenty of something. We listen to the child catalog thoughts and lost objects as if filling the void of sustenance. The empty stomach is repurposed into a container for the spam of life. Crammed with information, it becomes capable of expelling appetite and even anxiety from the system. Hunger, it seems to convey, is hunger for fabrication, not food.

Kot’átková’s installations tend to submerge the observer in such morbid enterologies of infant worlds. And infant worlds, we quickly gather, are no democratic assemblies. Working with collage, drawing, sculpture, film, and, lately, gallery walls, the artist has forged an idiosyncratic totality of these worlds over the years, which almost emulates an organism that sustains invariable aesthetics, yet generates ever-new contingencies connected to childhood. Kot’áková thereby characterizes childhood as a battery of …

May 2, 2017 – Review

Gallery Weekend Berlin

Sofia Lemos

In the wake of the events of May 1968, German Minimalist Charlotte Posenenske wrote in Art International that “it is difficult for me to come to terms with the fact that art can contribute nothing to solving urgent social problems.”,” Art International no. 5 (May 1968), n.p.] Posenenske’s “‘Statement’ [Manifesto],” which initially meant to examine ownership and the reproducibility of her artworks, publicly announced the artist’s dismissal of the art world. Having retrained as a sociologist, Posenenske dedicated herself to working with labor unions and refused to show her work or visit any exhibitions until her death in 1985.

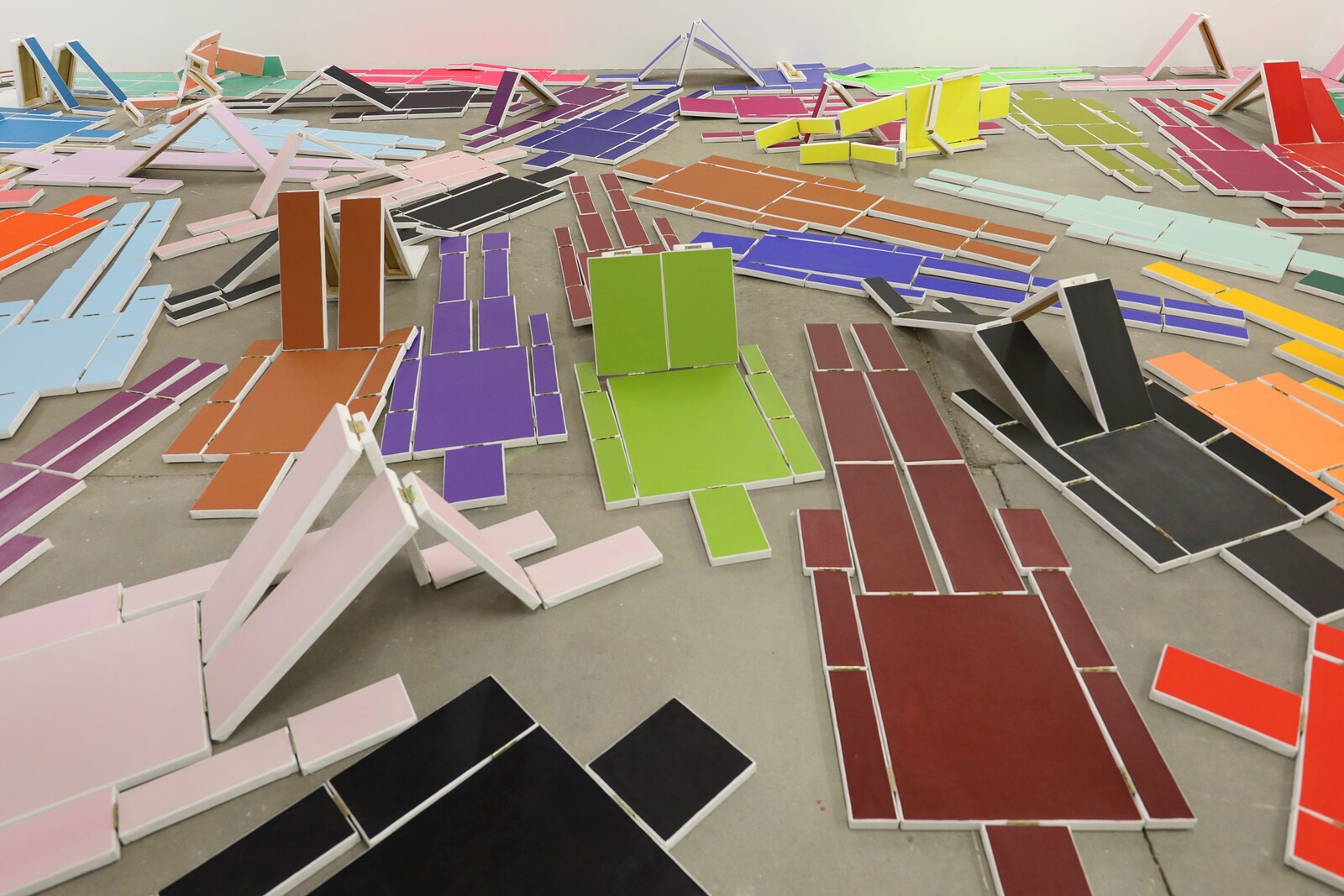

While gallery-goers shuttled through Berlin to the rhythm of scattered attention and market consumption, Posenenske’s show at Mehdi Chouakri set the tone for this year’s edition of Gallery Weekend Berlin. Selected galleries of all scales and scopes made a concerted effort to take up the conflated legacies of modernism, rationalized systems of language, and the critique of whiplash-paced figurations of the modern subject.

Mehdi Chouakri presents a series of abstract sculptures by Posenenske from 1967, as well as a selection of works on paper from the 1950s in their second space, also in Charlottenburg. Displayed in glass vitrines and hanging on the wall, …

February 16, 2017 – Review

Marcus Steinweg’s “For the Love of Philosophy”

William Kherbek

Descartes, Deleuze, Lacan, Nancy, Rilke, Weil, Heidegger (!) (just to name a few)—the gang’s all here at Marcus Steinweg’s new show at BQ, whose title, “For the Love of Philosophy,” certainly seems to ring true. “The self is the placeholder and performer of chaos. Descartes already knew this, that is why he wasn’t a Cartesian.” So reads one of the more gnomic assertions on Steinweg’s canvases. These works are positively overflowing with passion for his subject matter, and even if his references aren’t very geographically or culturally diverse, they are at least honestly engaged with, and speak of a deep and abiding commitment to the discipline and practice of philosophy. Steinweg’s canvas-as-parchment approach to the material, however, feels like a somewhat suboptimal marriage of form and content.

Steinweg presents 13 paintings from the series from which the exhibition takes its name. Cleaner and tighter than some of his earlier works on canvas, they feature sleek white digital letters printed on dark backgrounds, or a hide-and-seek of grey and yellow hues. Each presents a section of text, sometimes simply words, other times diagrams, or what might be regarded as a new sub-species of aesthetic literature, concrete philosophy: text arranged into layouts that …

January 25, 2017 – Review

Musa paradisiaca’s "Masters of Velocity"

Ana Teixeira Pinto

When writing the now-famous entry for the word informe (formless) in the surrealist journal Documents, Georges Bataille started by saying that “a dictionary begins when it no longer gives the meanings of words, but their tasks.” “Formless” is a word tasked with declassifying (déclasser), which in French also connotes degrading or debasing. Whatever gets called formless “has no rights of whatever kind and can get squashed at any moment, like a spider or an earthworm.”

Though Bataille had philosophical forms in mind—philosophy’s sole goal, he continued, is to dress in a formal frock coat everything that is—obsession with formal discipline extends beyond the philosophical register, to fields as diverse as visual art or biology. So much so that even formlessness has become a formal category. Amazon.com, for instance, presents Formless: A User’s Guide (1997) by Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss—in which Bataille’s dictionary entry appears as an epigraph—as a “rich and compelling panorama of the formless”: a taxonomy of forms of formlessness, so to speak.

The work of Portuguese artist duo Musa paradisiaca (Eduardo Guerra and Miguel Ferrão) is closer to what Bataille originally intended by his definition. Formlessness, in their approach, is not category but a task—one could say form follows …

December 21, 2016 – Review

Spiros Hadjidjanos

Elvia Wilk

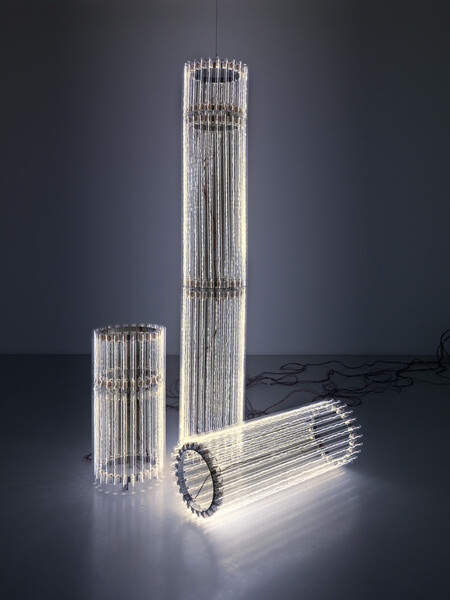

Spiros Hadjidjanos’s third solo show at Future Gallery is both technically and conceptually complex—it’s up to the viewer to decide how far down the rabbit hole to go. Yet each work functions on multiple levels, and is rewarding in equal proportion to how much time one dedicates to figuring it out. For instance, one could appreciate Hadjidjanos’s Network/ed Pillars (Taraxacum Officinale Arrangement) (2016) (part of the ongoing project “Network Time,” 2010–2016) installed in a new configuration in this untitled exhibition, solely on the level of aesthetic experience: in a darkened room of the gallery, a group of ten routers is arranged on the floor, each one with a fiber optic cable attached to a blinking LED light on its surface. The cables extend the lights up to the ceiling in long, bright vertical lines, creating a poetic visualization of their fluctuating signals.

Aesthetically seductive, this setup also illustrates several technical processes at work: each router generates an open wireless network and any device within range can automatically connect to one at random. So if someone in the room is connected to a network, the blinking of the respective router will change slightly, hinting at the action. This activity may be (barely) …

December 15, 2016 – Review

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s “QM.15” and “Costumes & Wishes for the 21st Century”

Antje Stahl

I was sent into darkness. I couldn’t see a single thing. There was a fuzzy light right behind the gallery door illuminating press releases laid out on a small table, and a gallery staffer equipped with a small flashlight. But she simply pointed into the dark: “That way.” That way was Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s exhibition “QM.15” at Esther Schipper in Berlin. That way felt like a ghost hall.

I heard a female voice singing an aria, but I had to pass by a life-sized moving image of a woman in a white uniform, fumbling my way along, before I fell over a rope that prevented me from reaching its source: an apparition of Maria Callas. A holographic illusion, to be more precise, of Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster playing Maria Callas: Opera (QM.15) (2016).

I don’t have a particular passion for being blindfolded. I hate ghosts, and I also hate costumes. A day before Halloween, Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon organized an event for people who are, I guess, excited about these things: a costume party as part of an exhibition. Produced by the artist in collaboration with the Berlin fashion designers BLESS and design studio Manuel Raeder, “Costumes & Wishes for the 21st Century” could be considered …

July 29, 2016 – Review

Michael Rakowitz’s “The invisible enemy should not exist”

Ana Teixeira Pinto

The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (Aj-ibur-shapu), from which Michael Rakowitz’s exhibition at Barbara Wien in Berlin borrows its name, was how the street which ran through the gate of Ishtar, in ancient Babylon, was known. Built around 575 BC under King Nebuchadnezzar II and dedicated to the goddess Ishtar, the gate was made of glazed brick covered in lapis lazuli and decorated with alternating rows of dragons and aurochs. Unearthed in 1899, the site where the gate originally stood was greedily excavated by German self-taught archaeologist Robert Koldewey, who lifted up the entire tower and shipped it to Berlin, where it still stands as the main attraction of the Pergamon Museum. Though Iraq repeatedly protested this heritage seizure, the gate—much like the ancient Greek Pergamon Altar, taken from present-day Turkey—was never returned.

In the nineteenth century, archaeology was a discipline mainly deployed in countries where its practitioners had no cultural relation to the population whose history they unearthed. When Europe elected Babylonia as the origin of (its) civilization, it did not simply appropriate its archaeological treasures, it also appropriated its history. Implicated in foundational myths and nation-building, archaeology became tied to colonial history: everyone has a claim to Babylon, except …

July 19, 2016 – Review

KwieKulik’s "The Monument Without a Passport"

Stefan Heidenreich

Resistance is a two-sided relation. It may also include more players, as we will discuss shortly. But losing its counterpart puts it in a difficult place. All political art has to deal with this dialectic entanglement.

In 1976, artists Zofia Kulik and Przemysław Kwiek were summoned to the Polish Ministry of Culture and Art in Warsaw. They were told that they were no longer allowed to represent Polish culture abroad. Their passports were withdrawn.

From 1971 onwards, both worked under the name KwieKulik. Until 1987, they produced what was considered one the most important bodies of political performances in Europe. In 2007, Documenta 12 showed Activities with Dobromierz (1972–74), a tableau of 48 black-and-white photographs documenting their newborn son surrounded by household objects, to be understood as a general reference to social relations and artistic practice. Then, in 2009, they were invited to the 11th Istanbul Biennial, and their work was rediscovered by a wider public.

The timing of their rediscovery—as much as the timing of the passport affair—is no coincidence. To understand the political aspects of KwieKulik’s work it is necessary to take a look at their resistance’s counterpart. In the mid-1970s, the Polish government (under First Secretary Edward Gierek, whose policy …

June 6, 2016 – Review

9th Berlin Biennale, “The Present in Drag”

Travis Diehl

“Advertisting … is the only art form we [in the United States] ever invented.” Gore Vidal

The fourth floor of Berlin’s Akademie der Künste overlooks Pariser Platz: the Brandenburg Gate, the French embassy fringed with barricades, a teeming Starbucks. Tourists mill around the square, while up on the mezzanine, between a set of marble statues of animals improbably swallowing other animals, a queue forms behind an Oculus Rift rig: Jon Rafman’s View of Pariser Platz (2016). At first the rendered scene in the headset matches the architecture and sculptures. A dog gags on a lion, an iguana gulps a sloth. Slowly, the animals start swelling, expelling, gyrating; the view fills with fog. Human figures blow upwards like flapping skins. Soon the pavement and building break apart; the viewer freefalls among the debris, landing, after a moment, among ranks of featureless mannequins… Rafman’s technical hallucination takes roughly three minutes. For three minutes, the setting in all its very real paradox—a symbolic gateway between West and East, Reagan and Gorbachev, also known as the place where Michael Jackson dangled his baby from a balcony—falls away beneath an encompassing, scripted but nonreactive spectacle. Thus the city rebrands itself: a new ad on a …

June 4, 2016 – Review

9th Berlin Biennale, “The Present in Drag”

Tess Edmonson

Berlin’s history of internecine violence is visible on its civic surface, a characteristic that holds currency in both mainstream and art tourism; what differentiates these two modes is a style rather than a politics. Who can say what a city means?

Gentrification mistakes lack of capital for lack of life, confuses the unexploited with the uninhabited. Over the course of its 18 years, the history of the Berlin Biennale has paralleled the drastic conversion of its symbolic center—the KW Institute for Contemporary Art and surrounding area on Auguststrasse—from post-GDR bohemia to a neoliberalism fully realized. For this year’s edition of the biennial, the ninth, curators Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso, and David Toro (known collectively as DIS) propose to orient audiences differently, moving the exhibition’s main venue to the Akademie der Künste on Pariser Platz, adjacent to the Brandenburg Gate, an area populated mostly by tourists, government officials employed in nearby offices, and police.

The appointment of DIS, best known as the publisher of the eponymous online magazine, exacerbated existing polarities among local artists and producers, where distrust of all that’s mediagenic, internet-literate, or American often barely disguises casual classism, or a nostalgia for the difference the city (and its art …

May 2, 2016 – Review

Gallery Weekend Berlin

Karen Archey

When the 7 percent value-added-tax rate on fine art went up to 19 percent in January 2014, it spelled to many the end of the Berlin art world. Proclamations followed that the market would dry up, and collectors would scatter to more cosmopolitan locales with less pricey export taxes. Without patrons or a steady stream of capital, how could Berlin’s artists thrive? The sheer volume of the jam-packed 2016 edition of Gallery Weekend Berlin suggests that the German capital’s art market is healthy as ever in its upper echelons, especially given the pricey 7,000-7,500 euro gallery participation fee, though younger galleries, perhaps hit hardest by the VAT rate update and who have largely figured these new expenses into the prices of their offerings, have seemingly responded with conservatism.

Two outliers to this trend are Aleksandra Domanović’s “Bull Without Horns” at Tanya Leighton and Alice Channer’s “Early Man” at Konrad Fischer. Domanović’s exhibition fills both of Leighton’s galleries, and includes her now-iconic sculptures featuring the Belgrade hand. Most unique in this exhibition are her new portraits of bulls that have been genetically modified to prevent them from growing horns. The large-scale, documentary-style photographs come off as earnestly tacky in a way that, …

April 11, 2016 – Review

Mary Reid Kelley’s “The Minotaur Trilogy”

Ana Teixeira Pinto

Pasiphae, the protagonist of Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s film series “The Minotaur Trilogy” (2013–15), was the queen of Crete, married to king Minos, the son of Zeus and Europa. Her story is a tale of offence and punishment, but not a straightforward one. Minos, who had just ascended to the throne, asked the god Poseidon for support. Poseidon sent him a white bull, which in Minoan mythology was no bull but the god himself in his pre-Olympian form. The bull was supposed to be sacrificed to Poseidon but Minos deviated from due observance and kept it instead. As a punishment, the god cursed the queen with the most unnatural lust: a sexual urge to mate with the nonhuman other, which was god and animal at once. In order to copulate with the bull, Pasiphae made Daedalus build her a casket in the form of a cow, with which she could arouse the bull’s libido. Mistaking it for a mate, the bull coupled with the man/machine contraption, impregnating the queen inside. Unfortunately for all involved, the materialization of Pasiphae’s monstrous desire was bound to be a monster: the Minotaur.

Mary Reid Kelley’s queen was inspired by, and partially adapted from …

December 22, 2015 – Review

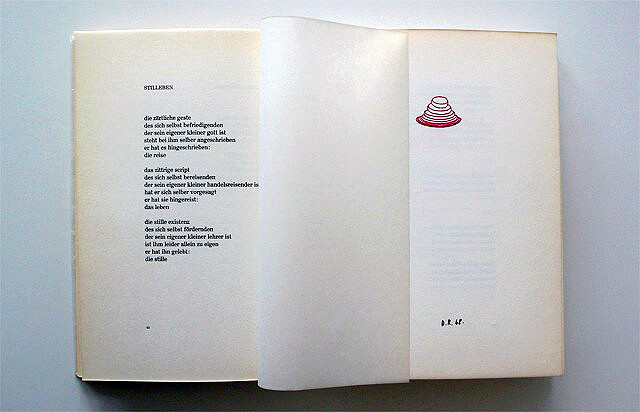

“Ich kenne kein Weekend. Archive and Collection René Block” (Part III/III)

Eva Scharrer

In tandem with “Ich kenne kein Weekend. Archive and Collection René Block,” a double-venue exhibition recognizing the work of gallerist, curator, and collector René Block organized in Berlin this autumn, art-agenda presents a three-part feature on Block. Parts I and II (available here and here) consist of an interview led by Luca Cerizza, while Part III, an introduction to the current Berlin exhibitions, written by Eva Scharrer, follows.

On September 15, 1964, René Block opened his gallery in West Berlin—thus opening a new chapter in art history. Fifty-one years later to the day, “Ich kenne kein Weekend. Archive and Collection René Block” is presented across two Berlin institutions: the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein and the Berlinische Galerie. Likely the first-ever retrospective of a curator, it looks back at more than five decades of exhibition-making between the art market and cultural politics. A publisher, dealer, facilitator, networker, pioneer of artists’ multiples, and curator, Block has organized more than 200 exhibitions and at least as many events, always shifting public perspective from the center to the margins.

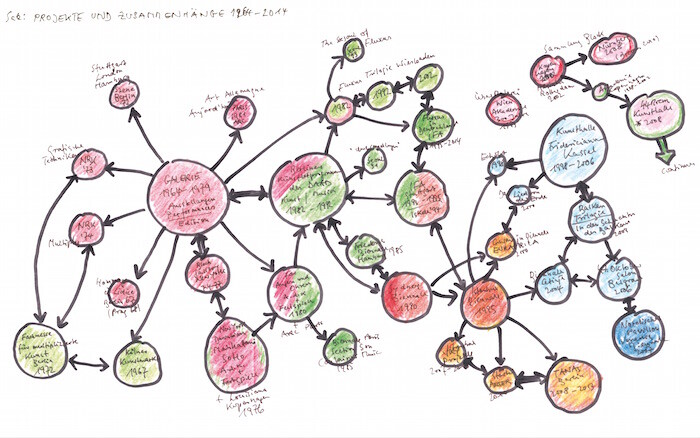

Entering each exhibition, one first encounters an enlarged drawing, a mind map consisting of a series of big and small circles, connected by various single or reciprocal …

December 16, 2015 – Review

Peter Fend’s “to be built”

Elvia Wilk

At first I had the feeling I was missing something when I encountered the documentation of unbuilt works by Peter Fend at his show “to be built” at Galerie Barbara Weiss, organized in collaboration with the project space Oracle. The drawings, prints, collages, and documents on display, mostly from the first 20 years of Fend’s practice, are billed as projects meant “to be built,” but if they’re really instructions, they’re hard to follow. For example, Delancey Street goes to the Sea, II, III, and IV, a series of quite beautiful collages from 1979, declares “CON ED / NO MAJOR GAS LINES DOWNTOWN,” with text overlaid on an aerial shot of lower Manhattan, followed by “SEA GAS INSTEAD,” the proposed solution. Red and orange lines drawn over the image demonstrate how waste pipes could be extended from Delancey Street across Brooklyn and into Jamaica Bay, and sea gas could be sent back again. Sounds like a good idea. But how, exactly, would sea gas get made from the waste? Could you really lay a pipeline in a straight shot across an entire borough? Who would finance the project? Wait, what’s sea gas again?

Fend is probably best known for his founding role …

December 8, 2015 – Review

The Gallerist: René Block and Experimental Music, 1965–1980 (Part I/III)

Luca Cerizza

In tandem with “Ich kenne kein Weekend: Archive and Collection René Block,” a double-venue exhibition recognizing the work of gallerist, curator, and collector René Block organized in Berlin this autumn, art-agenda presents a three-part feature on Block. Part I and II consist of an interview led by Luca Cerizza, while Part III is an introduction to the current Berlin exhibitions, written by Eva Scharrer. Part I follows, Part II will be published on December 15, and Part III on December 22, 2015.

The first time I met René Block with the proposal of writing a profile on his work as a gallerist for art-agenda, he mentioned a forthcoming exhibition and immediately took out a sheet of A4 paper on which he had drawn a colorful map. Composed of a series of circles of different colors connected by arrows, this sketch visualized 50 years of Block’s career, from the opening of Galerie Block in Berlin in 1964 to the planning stages, in 2014, of a double-venue Berlin exhibition on his life’s work. Almost one year later, on September 16, 2015, the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.) and the Berlinische Galerie opened the two-part retrospective “Ich kenne kein Weekend: Archive and Collection René Block,” …

December 3, 2015 – Review

Hito Steyerl’s “Left To Our Own Devices”

Ana Teixeira Pinto

Entering the philosophical lexicon during the eighteenth century, the term “aesthetic” is predicated on a double negation: its object is neither an object of knowledge, nor an object of desire. By introducing the notion of disinterest, Kant brought the concept of taste into opposition with the concept of morality. At the beginning of his “Critique of Judgment,” he illustrates his reasoning with the example of a palace, in which aesthetic judgment isolates the form alone, disinterested in knowing whether a mass of working poor toiled to build it. The human toll must be ignored in order to aesthetically appreciate an artwork. Art forms, we are told, operate at a remove from social forms. But this remove needs manufacturing. This is the role of the institution and the social technologies it employs. In her video installation Guards (2012), German artist Hito Steyerl shows how this space of Innerlichkeit [inwardness] is built on the backs of those it excludes.

The museum guards who work for the Art Institute of Chicago are all African-American—a makeup indicative of the over-representation of the city’s black minority population in low-wage jobs. From the reports by head of security, Martin Whitfield, and fellow guard Ron Hicks, we can …

November 9, 2015 – Review

Slavs and Tatars’ “Dschinn and Dschuice”

Ana Ofak

On the occasion of their nomination for the Preis der Nationalgalerie in 2015, Slavs and Tatars’ work can presently be viewed at two locations in Berlin. One is the Hamburger Bahnhof, the institution hosting the prize. There, books by the art collective are offered up for viewing in what looks like a swingers’ club for bookworms. By now, Slavs and Tatars have published ten books, making these the heart of their production. The other exhibition is at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler. Although the gallery show lacks the legs that lure and the dangling swings of the Hamburger Bahnhof presentation, it is far more daring. Together, the two sites unlock the universe of holistic heuristics Slavs and Tatars have been constructing for almost a decade. In this universe, the veils of obscurity that fell over the Eurasian territory, covering it in a neoliberal economy of uniform individualism, are lifted.

Slavs and Tatars are supreme wordsmiths. Hardly another letter in the pool of Slavic languages of Eurasia requires so much artistry in articulation or, for that matter, causes so much transcription trouble in the West as the Dž or Dż [d͡z] in the exhibition’s title. But “Dschinn and Dschuice” does not simply poke fun at …

September 18, 2015 – Review

abc art berlin contemporary

Tess Edmonson

As with all art fairs, the advent of Berlin’s abc art berlin contemporary brings with it a smallish number of collectors and a torrent of platitudes, most of them having to do with how depressing it is to look at art as though shopping. I wonder if it might be productive, however, to confront the idea that any grouping of artworks—at an exhibition, a fair, or elsewhere—is just a mess of saleable objects, despite one’s best attempts, through critical discourses, to see them otherwise. Near to the fair’s entrance, for example, Berlin’s Galerie Neu has a presentation of works from Swedish-born local treasure Karl Holmqvist. The booth hosts four identically sized prints on square canvases bearing Holmqvist’s idiosyncratic caps-lock text (poetry?) in simple black block characters on white, maybe like a painting of an .rtf file. Untitled (J/O&D.I.E.) (2015) repeats the title’s parenthetical phrase in lengthy succession, while Untitled (GONEJ/OANDDIE) (2015) makes use of the same group of words in sequence with another: “GOINGGOINGGONE.” For all their simplicity, Holmqvist’s text prints reject an economy of language, using repetition and permutation to expand and multiply rich and slippery meanings. In Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, she writes (quoting poet Anne Carson in …

July 14, 2015 – Review

Thomas Locher’s "Post-Information"

Ana Teixeira Pinto

Long before post-internet aesthetics and ubiquitous networking began to overhumanize technology, men in gray flannel suits were the standard metaphor for the dehumanizing nature of corporate technocracy. This expression, which swiftly became vernacular, stems from a 1955 novel by Sloan Wilson, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, describing the search for purpose in a pre-digital context amongst those who perceived themselves as just an organic extension of managerial structures. “Post-Information,” Thomas Locher’s current exhibition at Silberkuppe, in Berlin, is all about men in gray flannel suits—or rather, their absence.

In “Post-Information,” the display mirrors the subject matter: the exhibition spans two soberly staged rooms, which are metaphorically sealed off by the strategic positioning of an aluminium, shelf-like sculpture, Gestell (1990), obstructing the gallery’s entrance/exit. The series “Politics of Communication” (2000), shown in the second room of the gallery, consists of five large-scale composites of image and text. The pictures are of office furniture ranging from sleek to functional—at times as individual items (office chairs), at times as complete ensembles (workstations, conference rooms, storage systems). Each grouping is accompanied by text captions, which either describe or examine the tenets of communication theory: the nature of information, message, code, medium, and meaning. …

July 7, 2015 – Review

Bojan Šarčević’s “In the Rear View Mirror”

Stefan Heidenreich