As with all art fairs, the advent of Berlin’s abc art berlin contemporary brings with it a smallish number of collectors and a torrent of platitudes, most of them having to do with how depressing it is to look at art as though shopping. I wonder if it might be productive, however, to confront the idea that any grouping of artworks—at an exhibition, a fair, or elsewhere—is just a mess of saleable objects, despite one’s best attempts, through critical discourses, to see them otherwise. Near to the fair’s entrance, for example, Berlin’s Galerie Neu has a presentation of works from Swedish-born local treasure Karl Holmqvist. The booth hosts four identically sized prints on square canvases bearing Holmqvist’s idiosyncratic caps-lock text (poetry?) in simple black block characters on white, maybe like a painting of an .rtf file. Untitled (J/O&D.I.E.) (2015) repeats the title’s parenthetical phrase in lengthy succession, while Untitled (GONEJ/OANDDIE) (2015) makes use of the same group of words in sequence with another: “GOINGGOINGGONE.” For all their simplicity, Holmqvist’s text prints reject an economy of language, using repetition and permutation to expand and multiply rich and slippery meanings. In Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, she writes (quoting poet Anne Carson in italics), “What exactly is lost when words are wasted? Can it be that words comprise one of the few economies left on earth in which plenitude—surfeit, even—comes at no cost?”1 In a context where one is reminded precisely that art is not one of these economies—i.e., that everything comes at a cost—Holmqvist’s prints feel like a rare glimpse at pleasure that’s free.

They traffic in both modesty and maximalism, as do the three “Four-letter word sculptures” (all 2015) also on view at Neu, especially Untitled (Four-letter word sculpture KARL), an uncharacteristically monumental sculpture whose steel beams, at almost five meters tall, seem, at first, part of the architecture of the fair’s renovated industrial setting. A closer look reveals that each side of the rectangular sculpture is, rather, a letter articulated in steel: K, A, R, L. It’s just the artist’s own name, made enormous. Because what else are we doing, with contemporary art, than finding ever more precise ways of representing ourselves—our experiences, our politics, our ideas, our criticality? Holmqvist shortcuts the process with a gesture that is, appropriately, as vapid as the sudden realization that art is sold for money. It works exceptionally well.

Also exceptional is a solo presentation of works by Amsterdam-based Taocheng Wang at Amsterdam’s Galerie Fons Welters. In it, Wang records her experiences working part-time at a local Chinese massage parlor with a series of framed paintings and hand-written texts on rice paper. A Hongkong-Dutch client licking my arm during the massage treatment (2015) shows exactly that, in a flat and dreamy space, among a soft pattern of black and gold flourishes. The anecdotal texts speak to mutual support among the artist’s female colleagues in contrast to the lack of basic decency exhibited by their clients. Written in an imperfect English, one text contains the following passage: The man’s sunglass was looking at me up and down, it took half a minute, I piled up smiles and he suddenly said, “You were a guy before! I can recognize it actually. I mean, you were a guy!” Suny and Tracy immediately shouted out: “Sir! If you don’t want to have a massage, please leave our salon immediately! The door is open for you! And you should know how to speak well in front of ladies!” Wang’s body, and its gender performance, are subject to the client’s scrutiny—a small but exemplary reminder of the degree to which people assume the public is entitled to the bodies of women, especially those of color, especially at work in service industries.

The same entitlement is exhibited in Constant Dullaart’s presentation at the local Future Gallery, where the booth consists of a single image—that of a white woman sitting topless on an empty beach, her bare back facing the camera—distorted into a series of lenticular prints, as well as a wallpaper display. “Jennifer in Paradise” (2015) takes as its material “the first photograph ever to be photoshopped,” according to the gallery’s press release; it was taken by Photoshop co-creator John Knoll of his wife, Jennifer. I wonder if there wasn’t another way of exhibiting Dullaart’s research into the history of digital photography and manipulation, one in which the image’s provenance is paramount to pleasure in looking at naked female bodies? Why does this still happen? It’s 2015, and generally people now understand that using images of women in service of some greater artistic narrative is as boring as it is retrograde.

Authorship likewise makes a thematic appearance at the booth of Leipzig’s Galerie Tobias Naehring, where Berlin-based Lukas Quietzsch’s series “Kevin Kemter “BABYDOGG 1,000,000” produced by Lukas Quietzsch” (2015) translates the drawings of a fellow artist into paintings, though the question of authorship here isn’t really as interesting as how weird and unexpected the paintings are. A similar sense of surprise characterizes Viet Laurent Kunz’s presentation at Johan Berggren Gallery, Malmö, where painting and sculpture incorporate wood, plaster, graphic elements, and simulated natural materials. Three white works stand upright like plaster-covered trees, decorated with minute appendages: a small, carved hand, some glass eyeballs, fake flora, some steampunk tube things. The assemblage is precious and the scale is confusing, like a cool fairy landscape.

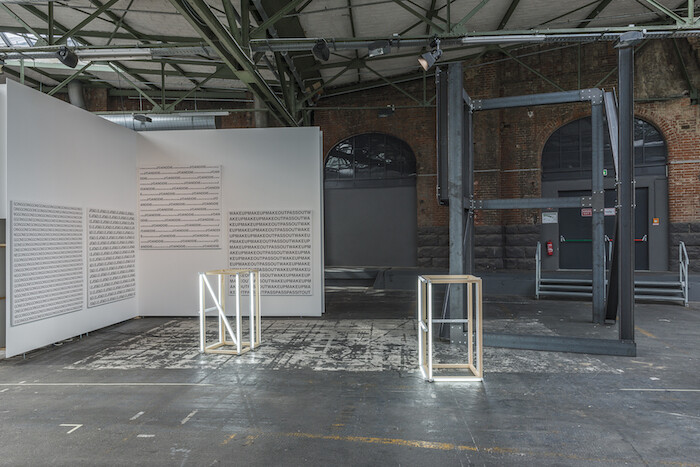

Nearby is Lydia Ourahmane’s large-scale installation The Third Choir (2014) at Dublin gallery Ellis King, a rectangular arrangement of 20 empty barrels imprinted with the logo of Naftal, an Algerian oil company, imported from Algeria. Inside of each, at the bottom, is a cheap Samsung cell phone. A central barrel contains a radio transmitter that relays a sound piece to each phone; amplified by each of the barrels, it’s a spacey, minimal, low-fidelity chorus. At Berlin’s Croy Nielsen, Mandla Reuter also makes use of ambient atmospherics with Confusion Mystery (2015), a lamp installed on the ceiling that suddenly changes, every half-hour, from a warm yellow light to a harsh, fluorescent, bluish one. It illuminates five sculptures, each titled Drain (2015): granite slabs that have been hand-carved into regular gutters and mounted on tall metal frames. Sparsely positioned, these humble gutters take on a kind of minimalist austerity, an impression that speaks to the transformational potential of contextual information. As in the exhibition of any kind of art—at a fair, or wherever else—things can change dramatically in the right light.

Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2015), 48.