If you are looking for an artist who really confronts the so-called “Digital Divide” and asks “what it means to think, see, and filter affect through the digital” (to quote from a critical dispute that recently played out in the pages of Artforum), then British filmmaker Ed Atkins is your man. Born in 1982, he has age on his side when it comes to relating to the digital experience and its effects. The pair of films on show at Isabella Bortolozzi, Paris Green (2009) and Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013), parenthesize a four-year development. During this time, Atkins has moved from a production process still rooted in the real world (real-time footage of recognizable things) to its total consumption through the technological possibilities of the digital (all imagery now being produced within the interface of the computer.)

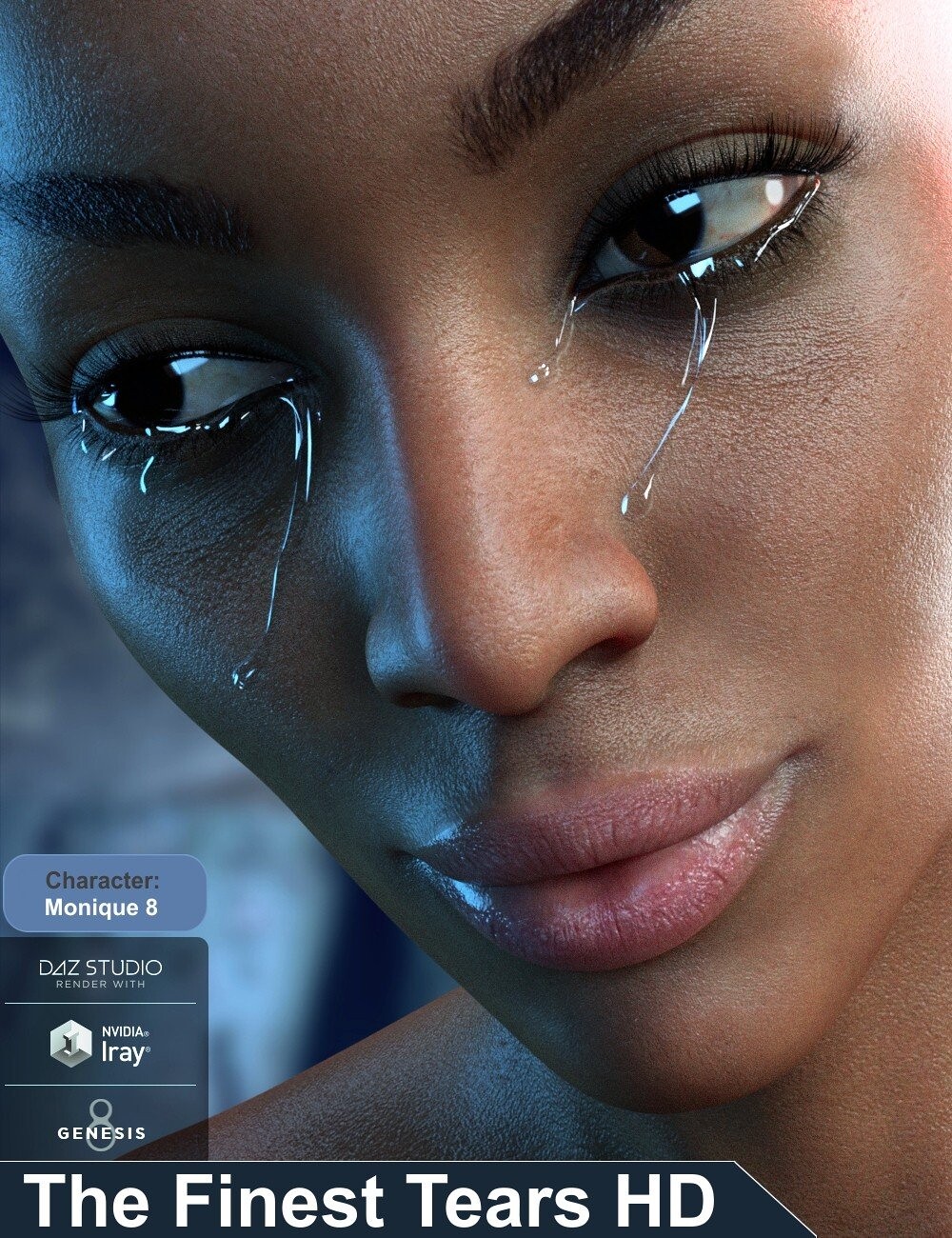

As tactile as its title may be, the new work, Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013), pictures the digitalization of existence from the inside, in all its cold alienating surrogacy. We see the head and taut, muscular torso of a man sitting on a chair in a digital no-space, with a mane of incredibly long straight hair, sometimes combed right over his face to hang down in front of his chest, or else floating in snaky tendrils around him, as if underwater. The image is composed of layers of perfectly simulated textures: synthetic glare, liquid drops, perfectly rendered skin, eyes, smears, splashes, shadows. The hair, with its gravity-defying simulated strands, seems to be there just to demonstrate the heights of digital virtuosity: it looks so real. But just what is it that we are looking at?

Spoken text and written words that appear in strips across the bottom of the screen speak of despair, death, pain, estrangement. A refrain, borrowed from poet Gilberto Sorrentino, beginning “I don’t want to hear any news on the radio about the weather on the weekend,” returns at intervals. “A site of total DEPRIVATION” says the character who, through motion sensor software, replicates the mouth movements originally performed by Atkins himself. “Presence is something we need convincing of,” he (it?) says. “… And all this fucking hair.”

All this fucking hair is thematically omnipresent in the exhibition. In one room, large panels lean against the wall, adorned with enlarged black-and-white photocopies of synthetic hair loops, like the hair-dye color matchers you find at the hairdressers. They make their point, but it’s hard not to see them as unnecessary space fillers (coming soon to an art fair near you?), which do little to bolster the film itself.

The digital realm is like being underwater, a site of total sensory deprivation, Atkins’s film suggests. There are no warm mouths here, nor tactile surfaces. As the avatar raises his index finger towards us, he touches the screen from the inside— the digital divide itself—as if pressing a button on the interface, with a reassuring click and a simulated surface bubble. Only a tiny sliver of reality is needed from which to create all this. The creative possibilities seem inexhaustible, and the gulf between this heroic expansive horizon and the very real limits of our fragile bodies, condemned to mortality, and connected only by a keyboard, seems increasingly unbridgeable. But nevertheless, technology cannot make life. And this is the nub of Atkins’s new film, as well as its predecessor Us Dead Talk Love (2012) from which the new film’s title derives (and both of which are currently on view, at PS1 in New York.) That is to say, the impossibility, as the earlier film describes, “to create something already dead, un-lived, but with the qualities of something that had lived. DIED.” As the technical proficiencies of the digital age advance, we approach an impasse: the so-called “Uncanny Valley” itself, perhaps, whereby simulacra that become too close to human reality are met with revulsion and rejected.

It is through recourse to the spoken or written word that Atkins is able to overcome the revulsion that his imagery elicits. In this exhibition, as in all of his recent shows, a printed booklet is available to take away. This contains a text by Atkins, somewhere between loose script and extended poem that acts as an analog counterpart to the film’s digital imagery. The best way to experience one of Atkins’s works, in fact, (and indeed perhaps the only way, for someone such as myself, on the wrong side of the digital age divide) is as a three-part, time-based experience: first watch the film, then read the text, then watch the film again. Atkins has described his writing as “gratuitous” as opposed to the more reductive, tightly edited films, which reduce information to such a streamlined minimum that comprehension can be haphazard, or elliptical at best. The text restores depth to the surface-rich images. Taken together, they articulate the quandaries of being human in the digital age.

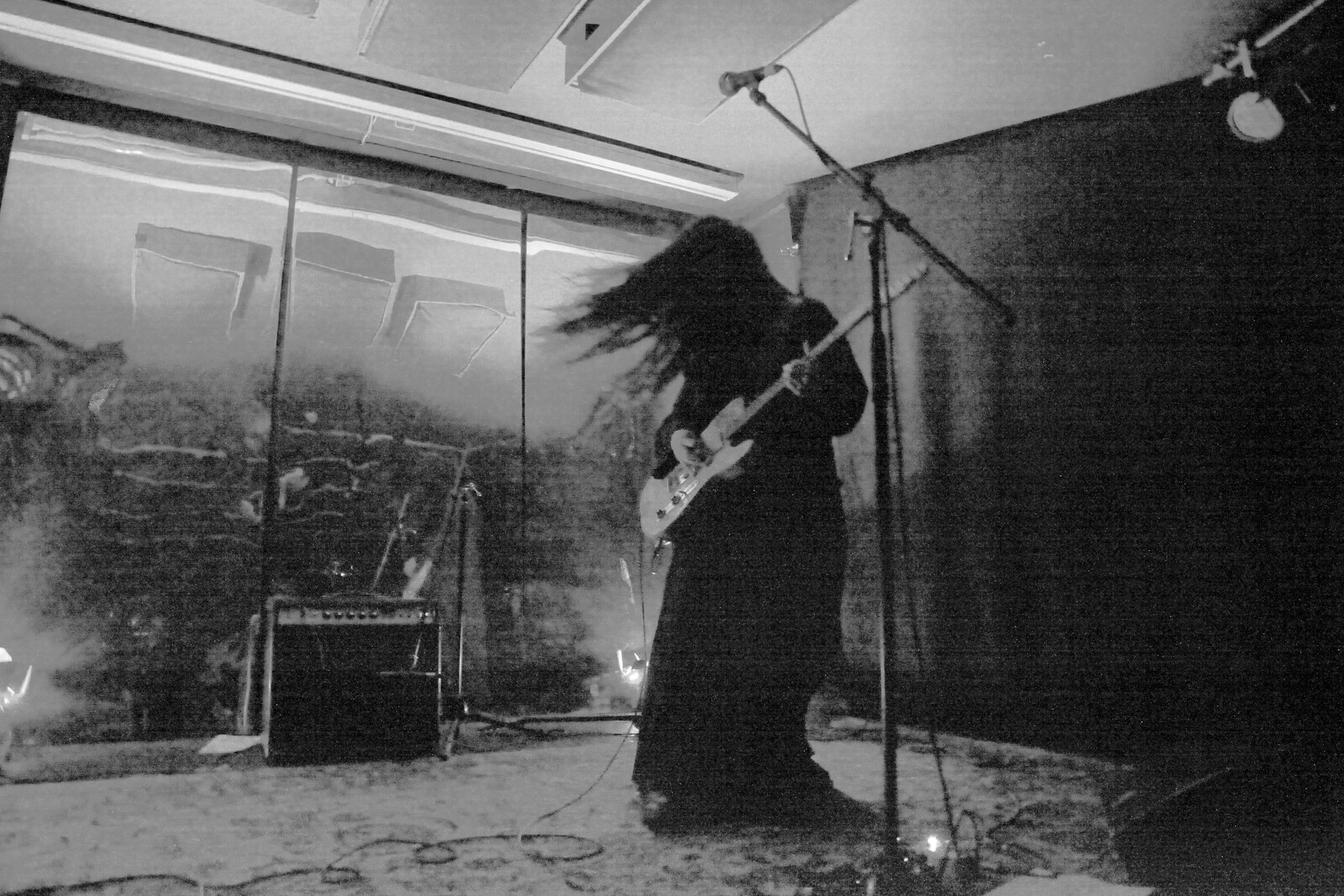

We are not offered the text to the earlier film shown here, Paris Green (2009), however, a nature film of sorts which remains elliptical, if more visually approachable. Footage of a bright green tropical forest, shots of sunlight shining through branches, piles of dead leaves strewn with feathers or close-ups of guitar strings are accompanied by a soundtrack of synthesized choruses, strumming guitar, or dull mechanical clicks as the edit shifts from green screen to moonlight, strobe or fluorescent strip lamps. Light sources and photosynthesis are set in opposition to the zero-backdrop of the digital green screen, while acoustic vibrations pose a counterpoint to synthesized sounds. Here there is still room for maneuver between digital effects and their real world counterparts, unlike the claustrophobic, anxiety-inducing atmosphere of Aktins’s Mouths, consumed by the interface, in which death and its digital doppelgänger attempt to switch places.