In tandem with “Ich kenne kein Weekend. Archive and Collection René Block,” a double-venue exhibition recognizing the work of gallerist, curator, and collector René Block organized in Berlin this autumn, art-agenda presents a three-part feature on Block. Parts I and II (available here and here) consist of an interview led by Luca Cerizza, while Part III, an introduction to the current Berlin exhibitions, written by Eva Scharrer, follows.

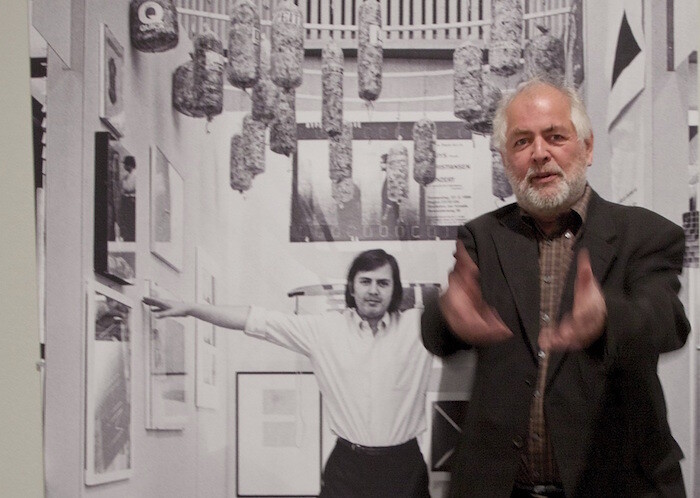

On September 15, 1964, René Block opened his gallery in West Berlin—thus opening a new chapter in art history. Fifty-one years later to the day, “Ich kenne kein Weekend. Archive and Collection René Block” is presented across two Berlin institutions: the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein and the Berlinische Galerie. Likely the first-ever retrospective of a curator, it looks back at more than five decades of exhibition-making between the art market and cultural politics. A publisher, dealer, facilitator, networker, pioneer of artists’ multiples, and curator, Block has organized more than 200 exhibitions and at least as many events, always shifting public perspective from the center to the margins.

Entering each exhibition, one first encounters an enlarged drawing, a mind map consisting of a series of big and small circles, connected by various single or reciprocal arrows. Together they represent the various chapters in Block’s career as exhibition-maker, and illustrate how everything is connected. In addition to the circles standing in for Block’s gallery in Berlin and later New York (1964–79), the central stations of this constellation are the German Academic Exchange Service DAAD (1982–92), where Block was responsible for the art and music sections, the Kunsthalle Fridericianum in Kassel (1997–2006), and several international biennials since the 1980s.

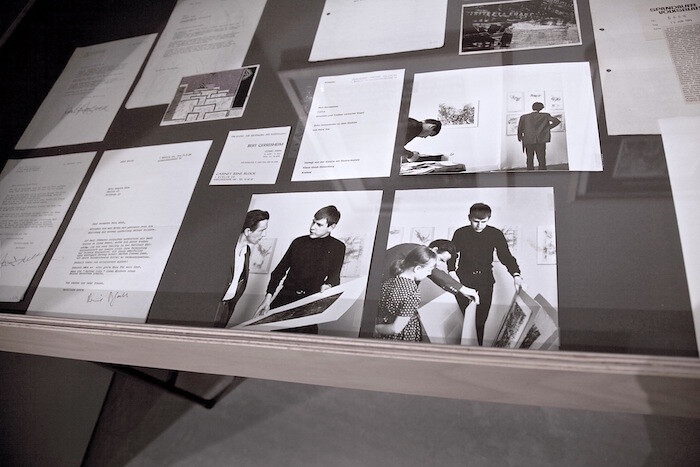

At the Berlinische Galerie, Block’s life’s work, or, as he likes to refer to it, his “curatorial building,” is reconstructed from archive material—correspondences with artists, invitation cards, posters, programs, price lists, publications, photographs, and videos—as well as selected artworks and editions that played a significant role in his career. The presentation is dense; however, it provides only a glimpse of the materials that have been produced and collected over the course of Block’s practice.

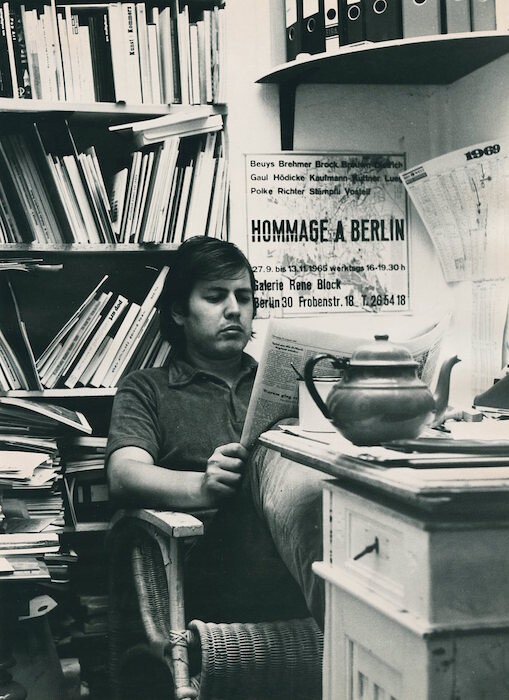

The story that is told here begins in Berlin-Schöneberg, where the 22-year old Block, who had just come to Berlin from his native Lower Rhine region to continue his art studies, had rented a humble basement apartment to open a programmatic “Kampf- und Programmgalerie”1—a corrective tool within the context of state-subsidized, mostly abstract art production fashionable in West Berlin at that time. With Block Galerie’s first exhibition, entitled “Neodada, Pop, Decollage, Kapitalistischer Realismus,” Block scored a coup. He brought a still unknown group of young artists, including Gerhard Richter and Konrad Lueg (the latter also subsequently known as gallerist Konrad Fischer), who had just announced Capitalist Realism as an answer to both American Pop Art and the Socialist Realism of the GDR, from Düsseldorf to the island-city of Berlin, alongside the already more established Joseph Beuys and Wolf Vostell. At “Ich kenne kein Weekend,” the creative origins of the gallery can be read in Block’s letters related to this first exhibition. For instance, the moment when Richter happily accepts Block’s invitation to a “demonstrative exhibition” in June 1964, promptly taking the chance to also recommend Sigmar Polke, at that time still a student, to Block—as he was, in Richter’s words, “a Pop Artist like Lueg and me.” In the same vitrine, one also discovers letters from the same year that Block wrote to Dada veterans Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch, inviting them to his gallery. While Hausmann responds, “Why show Neodada when the Dadaists are still alive?”, Höch excuses herself with a beautifully drawn postcard.

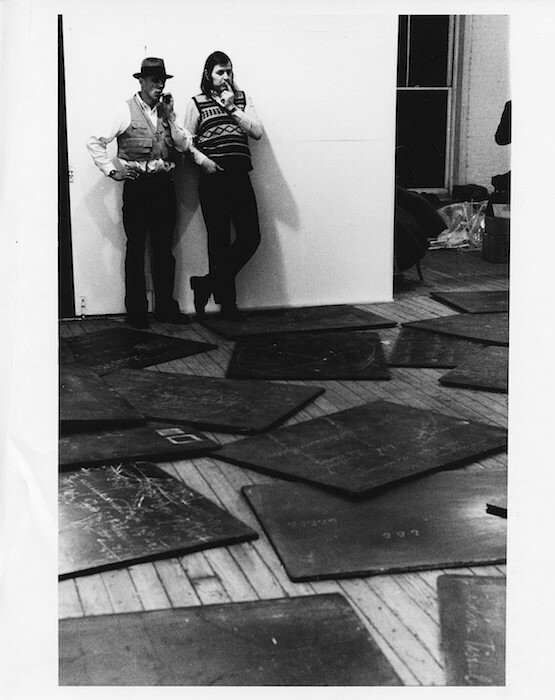

Observing the carefully designed early printed matter and catalogues published by Block leaves little doubt that they were meant to be part of a larger oeuvre from the beginning, a legacy that might end up a museum. And here it is. From piece to piece, the aforementioned curatorial building enfolds, with Beuys, Fluxus, and music as cornerstones. There is rarely seen documentation of the many soirées, performances, happenings, and Fluxus concerts that played a major role in Block’s intermedial gallery program—among them Wolf Vostell’s first happening in Berlin at a car dump (Phänomene, 1964), or Allan Kaprow’s Sweet Wall, which he erected with a handful of participants in November 1970 on an empty lot near the actual Berlin Wall using bricks, bread, and marmalade. Less known are the first institutional exhibitions that Block organized in the 1970s: “The Berlin Scene 72” in Stuttgart, London, and Hannover; two thematic shows about graphic techniques and multiples (his personal interests as a producer and dealer) at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein; and one at Berlin’s Akademie der Künste in 1976 about New York’s emerging artists’ quarter in SoHo. Two years previous, Block had opened a satellite of his own gallery in SoHo with Beuys’s legendary performance I like America and America likes Me (1974), in which the artist, having been driven from the airport to the gallery in an ambulance and wrapped in felt, spent days locked in a cage with a coyote, before leaving the US the same way he came. On September 15, 1979—at which point many of the artists with whom Block worked were commercially successful—Block closed the gallery. Under the laconic exhibition title “Ja, jetzt brechen wir hier den Scheiß ab” [Yeah, let’s end this shit now], Beuys hammered the plaster off the walls. Block, who was, after all, the co-initiator of the first art fair in Cologne in 1967 (Kunstmarkt Köln, now Art Cologne), and organizer of the 3rd and 4th Internationale Berliner Frühjahrsmesse (International Berlin Spring Fair), left the market just before the big commercial boom, and moved into new fields of activity.

Significantly, the first big institutional show that Block organized as an “independent” curator was under the framework of the Berliner Festwochen at the Akademie der Künste in 1980, and explored the intersections of visual art and music. “Für Augen und Ohren” [For Eyes and Ears] brought a range of musical “outsiders” to Berlin to perform concerts—one of them, the Paris-based Russian composer Ivan Wyschnegradsky, who occupies (along with Beuys, Polke, and Vostell) an entire vitrine in the exhibition. Among the other projects represented are “Art Allemagne aujourdhui” (1980) at the Musee d’art moderne de la ville de Paris, the first-ever dedicated presentation of contemporary German art in France, and a trilogy of Fluxus retrospectives (1982, 1992, 2002) in Wiesbaden.2 Subsequently, with biennials in Sydney (1990), Istanbul (1995), and Gwangju (2000), Block established himself as one of the first global curators (though he’d always prefer the term “exhibition-maker”), and at the beginning of the new millennium, after having meanwhile become artistic director of the Kunsthalle Fridericianum, he departed once again into new territories with the extensive “Balkan-Trilogy” of exhibitions and programs devoted to contemporary art in and from the Balkans.3, 2003, at Kunsthalle Fridericianum, followed by “In den Städten des Balkan” [In the Cities of the Balkans], 2003-04, a dense program of exhibitions and conferences in Istanbul and various Eastern European cities, and the Cetinje Biennial V, “Love It or Leave It,” 2004.] Back in Berlin he opened a project space, Tanas – Space for Contemporary Turkish Art (2006-13), as well as a new gallery in which to showcase artists’ multiples: Edition Block, which still exists today. Among the many editions produced by Block is Weekend (1971/72): a suitcase with prints by, among others, KP Brehmer, K.H. Hödicke, Arthur Koepcke, and Sigmar Polke, so that the art-loving frequent traveller could always carry his or her favorite pieces anywhere. When Block asked him to participate, Beuys reportedly answered, “Ich kenne kein Weekend” [I know no weekend], before contributing a ready-made Maggi-brand spice bottle with an edition of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason from German publisher Reclam—the line named both the work and this retrospective.

At Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, the exhibition’s second venue, Block presents a very personal selection of his very own favorite pieces. Starting with leftovers from the gallery—“good art never sells well,” he states4—Block built a collection over the years based on close relationships with artists, with Fluxus at its heart. Among the treasures are scores, drawings, and conceptual collages by John Cage, Stanley Brouwn, Jarosław Kozłowski, and Sigmar Polke; “I am still alive” telegrams by On Kawara; annotated Life magazines by Nam June Paik; a small painting by Richter; a vitrine featuring a dust-drawing and the remains of a potato harvest Joseph Beuys made in the front garden of Galerie René Block in 1977; and delicate arrangements by Robert Filliou and Claus Böhmler. In their present installation, these works enter a dialogue with those of younger generations, namely women artists from Turkey and Eastern Europe, like Nevin Aladağ, Aydan Murtezaoğlu, Sanja Iveković, or Alicja Kwade. “Ich kenne kein Weekend” may summarize the work of fifty years, but it certainly doesn’t put an end point on it.

“Kampf- und Programmgalerie” was Block’s term, which translates literally as “fight and program gallery.”

“1962 Wiesbaden Fluxus 1982” at Museum Wiesbaden, Nassauischer Kunstverein, and Harlekin Art, Wiesbaden; “Fluxus da Capo,” across nine different venues in Wiesbaden in 1992; and “40 Jahre: Fluxus und die Folgen,” at Karstadt, Projektbüro Stadtmusseum, Nassauischer Kunstverein, and other venues in Wiesbaden in 2002.

This trilogy consisted of the exhibition “In den Schluchten des Balkan. Eine Reportage” [In the Gorges of the Balkans: A Report

From a press conference marking the exhibition’s opening.