It is unusual that a work sums up an artist’s practice and sensibility so acutely and simply as the single piece exhibited in Cerith Wyn Evans’s “Assemblage” at Galerie Neu. Imagine the bling of an enormous Murano glass chandelier, blinking its way through a score of Bataille in Morse code, combined with the flash of a circle of words set in fireworks that blaze and burn out, and filtered through the fleeting gorgeousness of a thought in white neon (“Thoughts unsaid, now forgotten”) and you’ll get a sense of this work.

Wyn Evans is a practiced évocateur, bearing armfuls of weighty intellectual or cultural references (Pasolini, Stein, Debord, Mallarmé) while not shying from the seductive possibilities of their packaging: crystal chandeliers, fireworks, neon, mirrors, music, mobiles. Though the works themselves may appear like ephemeral thoughts suddenly clothed in three dimensions, they embody desire just as much, while revealing the impossibility of capturing either. Light, heat, reflection, sound, air: the qualities Wyn Evans employs to animate his works are themselves transient, determined by the perception of the viewer. In Assemblage, a lack of permanence permeates—and the essentially tragic passage of time, whether the simple fact of our mortality or the compound losses of fallen civilizations, finds a dramatic conclusion.

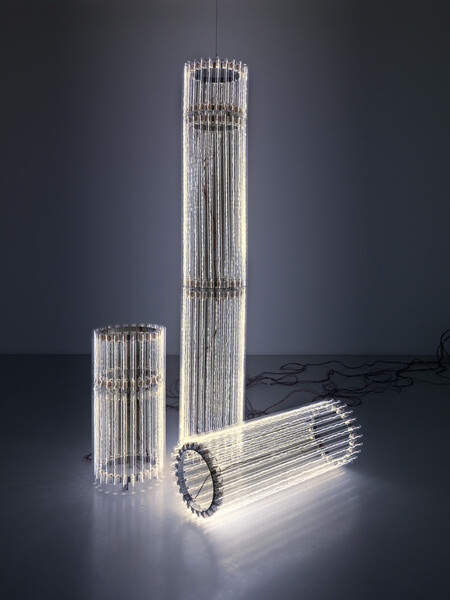

With typical boldness, Wyn Evans takes a hackneyed romantic cliché and combines it with an unexpected material, the potential of which allows him to possess the symbol completely and create a newly vibrant image of our own temporal materiality. Assemblage is composed of three units: an upright column, just over two meters high, composed of three sections; a smaller column about a third of the height standing next to it; and a single column lying, fallen, horizontally on the floor. These Doric columns are made of clear fluorescent tubes, each with a single fine electrical filament which not only blazes a bright line of light, but also emits a palpable, if somewhat alarming, heat. Threatening to burn out at any moment, or even burst their fragile glass encasings, the end—or even disaster —seems immanent, even in these symbols of a collapse that already happened. Do they refer to the ancient past, or to a more recent modernism forged from fluorescent lighting? The ghosts of many artists hover: Dan Flavin, of course, but also Felix Gonzalez Torres, and more recent ghostly presences, like Hilary Lloyd, or Olafur Eliasson, though all of these are in constant competition with the actuality of the work, as felt through its urgent waves of heat. The references are felt rather than spelt out. As the artist himself said in a recent interview: “My work is profoundly concerned with the history of these ideas, but through the ghost of the experience rather than an immediate engagement with it.”

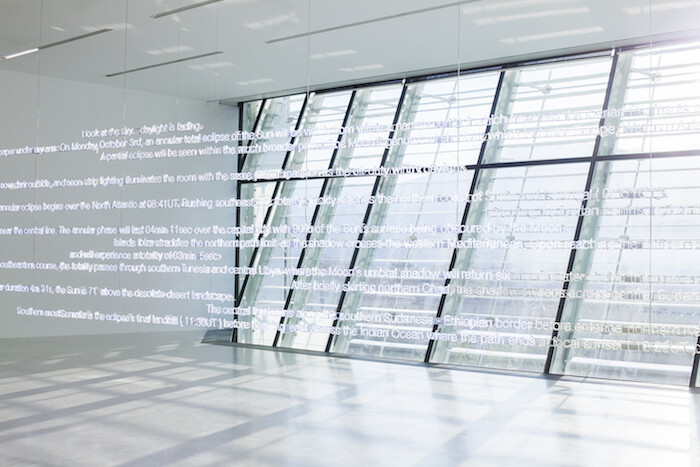

This exhibition at Galerie Neu is pendant to Wyn Evan’s exhibition at the Kunsthalle in Bergen where a work originally shown in London’s White Cube almost a year ago is on display. Entitled S=U=P=E=R=S=T=R=U=C=T=U=R=E (“Trace me back to some loud, shallow, chill, underlying motive’s overspill”) 2010, it is installed in a darkened room: seven classical columns made from fluorescent lighting, each over five meters high, reaching from floor to ceiling and reflected in the floor’s dark, polished surface. A penetrating sound of long drawn-out notes from glass flutes suggests an aural sense of limbo that backs up the material limbo of the ghost architecture. Though this is a fine example of the polyphony and overlapping sensory experiences that often occur in Wyn Evans’s practice, the single broken column, alone and quiet in Neu’s bright gallery, says it all.