For this show, knowing too much before seeing may not be helpful, and may even spoil your viewing experience. Bojan Šarčević is an artist who doesn’t like to wrap his art in too much information. Objects and works are supposed to stand for themselves. At his show at Berlin’s BQ, no item bears a title. Press release and handout, both formats which have become standards of gallery communication, are missing. The spectator is left with what is there, and supposed to figure out what that is for herself. Šarčević’s refusal to give additional information reminds us of the degree to which we as observers have been lured into a position that makes us complicit in a certain game of producing and circulating meaning. Given all the research on art and the observer, I wonder if anyone ever cared to investigate the discursive role of metadata, the format of small texts accompanying works of art, and the paratext around exhibitions.

There was a time, at the peak of modernism, when artworks were meant to create a direct, non-verbal line of communication between the artist and the observer, free of references and full of subjectivity. Back then, artistic autonomy was taken for granted and the artist still figured as a heroic genius. Of course, Šarčević does not intend to switch back to these historically outdated attitudes. Rather, he asks us to engage in a kind of perception that is not or pre-formatted or pre-structured by advance knowledge.

Maybe this position is also due to an experience he had with the first iteration of the show, under the same title, in Genoa at Pinksummer Gallery in autumn 2014, which was nearly the same but with slight variations. At the time, the gallery produced a press release that attempted to do what a press text is supposed to do: to explain everything and to spruce it up with an abundance of links to cultural history, hoping to glean both recognition and importance.

Unfortunately, in my search for information about this current show, I stumbled upon this text, and it gave so much background on the show that now I can no longer look at it unprepared, as the artist intended me to do. Marshall McLuhan made the distinction between hot and cold media: a cold medium deprives the viewer of information, and in doing so engages her in the inventive impulse to compensate for its shortcomings. It produces, paradoxically, more involvement. In this respect, the Italian press release turned the show from a cold to a hot one, mitigating its imaginative power.

But maybe I should have known from the beginning what this show was referring to. Some years ago, I met the artist at Bar 3 in Berlin, and he told me about his hut in the Apennine Mountains. It is supposed to function as a lodge for walkers, but also as an open space and a work of art. Linking the show with this project suggests a clear, and maybe overly simple interpretation. But I have always had the impression that one can straightforwardly access Šarčević’s work by taking it in a very literal, direct sense. Of course, I could also link the title of the show to a novel, the title of a movie, or a song. But the view in the rearview mirror could also be simply the last glimpse back to the construction site before you turn the corner. Did I leave the hut in a proper state? Did I lock up all the tools? Did we get done the work that we wanted to?

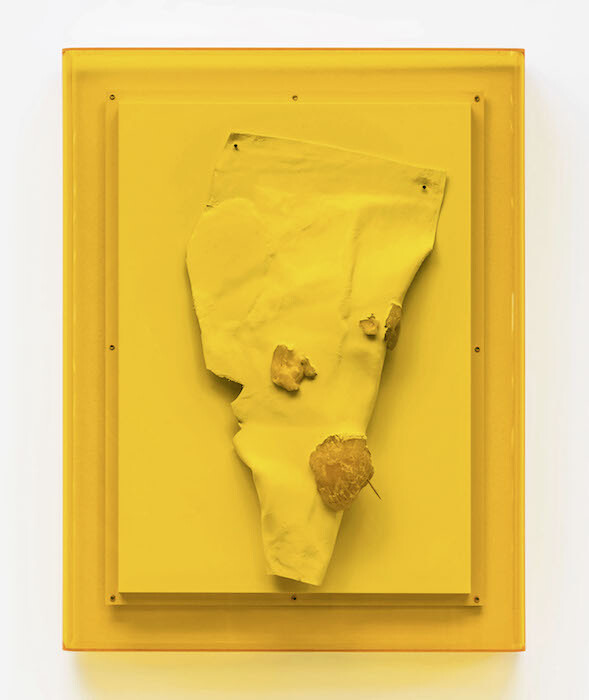

Of all the works in the show, 20 altogether, I want to single out 2. Not the fragile wooden constructions that look like racks or window blinds for mosquito nets, of which the artist produced a urethane reproduction in a second room (both works Untitled, 2014 and 2015, respectively). Not the Arte Povera-like sculpture looking like a miniature hammock (Untitled, 2014). Not the meshworks of textiles and plaster folded into erratic shapes as if the skin of the house and the artificial textile skin of humans were to breed new forms of half-life (Untitled, 2014, and Untitled, 2014/15), and also not the two-meter-tall dark gray Styrofoam model of a wall (Untitled, 2014).

There is a vitrine containing three pieces: a model of the hut, an assemblage of wall elements, and two skin-colored silicone patches placed on a folded piece of light blue cloth. The vitrine seems to indicate that we’re looking at something beyond the view in the rearview mirror, like a distant thought reaching back to the initial planning phase of the mountain lodge. And then, there is the eye-catching photo of the exhibition. It shows a topless, nearly bald guy in jeans. It’s taken from behind, most likely either in the studio, with some of the exhibited works in the background, or in the hut itself. A silicon breast implant is attached to his bare back. This could open the door for all kind of sexual associations and reflections on gender roles. But it may also just be read as a comment on the situation of male workers being up in the mountains for a week, on thoughts and conversations during those days and evenings, showing up as a memory once they have left the place. However, dwelling is a mode of being, and constructing a house is a material process of subjectification, from choosing the location to erecting a shelter into which a human body can enter, and that a human being may call a home. And as such, the show turns the very concrete reference to the building from a hot issue into a cold one that casts new existential questions.