Like the images of empty streets of his hometown Düsseldorf, and the cities he visited and photographed as a young artist in the late 70s and early 80s—New York, Rome, Paris, Brussels—Thomas Struth’s recent group of photographs depict the landscapes of technological infrastructures in which the makers of these structures (i.e., human beings) are largely absent. With some of his largest works to date, this exhibition included fifteen exquisitely rendered documents from the artist’s travels to places like Geoje Island in South Korea or Cape Canaveral, Florida, as he visited research centers, laboratories, and construction sites dedicated to the development of new technologies but largely invisible to the collective imaginary.

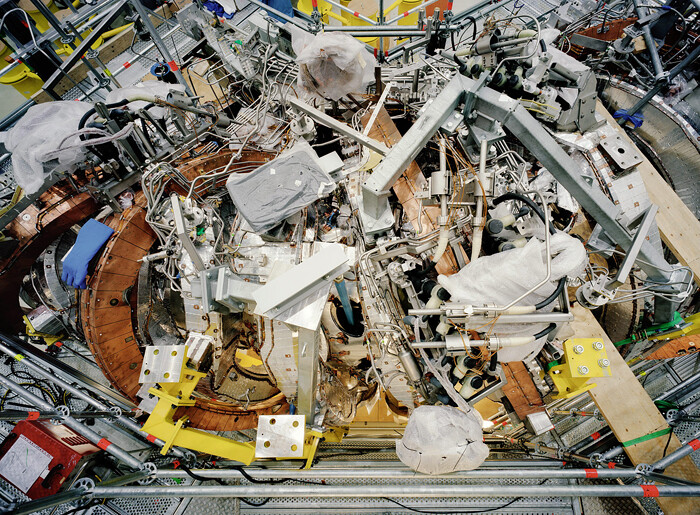

Tangles of brightly colored cables and tubes, i.e., the innards of machines, have been shot from a proximity that inhibits a central perspective, making it impossible for any layperson to identify what they are seeing (or comprehend even after reading about them on the Internet) in works like Stellarator Wendelstein 7-X, Detail, Max Planck IPP, Greifswald or Tokamak Asdex Upgrade Periphery, Max Planck IPP, Garching (both 2009). The result is an experience of visual and conceptual vertigo, seductive in its dizzying capacity to make the viewer feel small and insignificant—an operation akin to that curious wedding of confusion and reverie present in the artist’s more overt engagement with the sublime, for example, in his “Paradise” series (1998-). Similarly, in Space Shuttle 1, Kennedy Space Center, Cape Canaveral (2008) a miniscule pair of wheels is barely discernible in the extreme background of the photograph. Were it not for the title, they would have been lost in the maze of scaffolds wedged under the massive underbelly of a spacecraft meant to be seen vertically, as it points to the sky illustrating the pathos of conquest.

Metonyms of the absent subject appear casually here and there, like fissures in a machine (or system) that, no matter how perfect, is still prone to human error (or greed, as the case may be)—a single glove discarded among the contents of the said stellarator or the graffiti of a bored technician who has scrawled the words “J’ai mal au nez” (I have a sore nose) on a glass panel behind which noxious gas-filled red and yellow balloons playfully hover (Chemistry Fume Cabinet, The University of Edinburgh, 2010). And then there are the two tiny shipyard workers in Semi Submersible Rig, DSME Shipyard, Geoje Island (2007) tinkering with their bicycles in the shadow of a gargantuan offshore platform (not unlike the one that exploded in the Gulf of Mexico three years after this photograph was taken).

With their monumental proportions and technical precision, these works seem to embody the hubris of technology while laying bare excruciatingly banal details with a dispassionate objectivity. But Struth’s photographs harbor empathy toward what they alternately show, suggest or conceal. Traces of this suppressed subjectivity are sometimes visible but usually relegated to a conceptual frame beyond the two-dimensional.