Entering the philosophical lexicon during the eighteenth century, the term “aesthetic” is predicated on a double negation: its object is neither an object of knowledge, nor an object of desire.1 By introducing the notion of disinterest, Kant brought the concept of taste into opposition with the concept of morality. At the beginning of his “Critique of Judgment,” he illustrates his reasoning with the example of a palace, in which aesthetic judgment isolates the form alone, disinterested in knowing whether a mass of working poor toiled to build it. The human toll must be ignored in order to aesthetically appreciate an artwork. Art forms, we are told, operate at a remove from social forms. But this remove needs manufacturing. This is the role of the institution and the social technologies it employs. In her video installation Guards (2012), German artist Hito Steyerl shows how this space of Innerlichkeit [inwardness] is built on the backs of those it excludes.

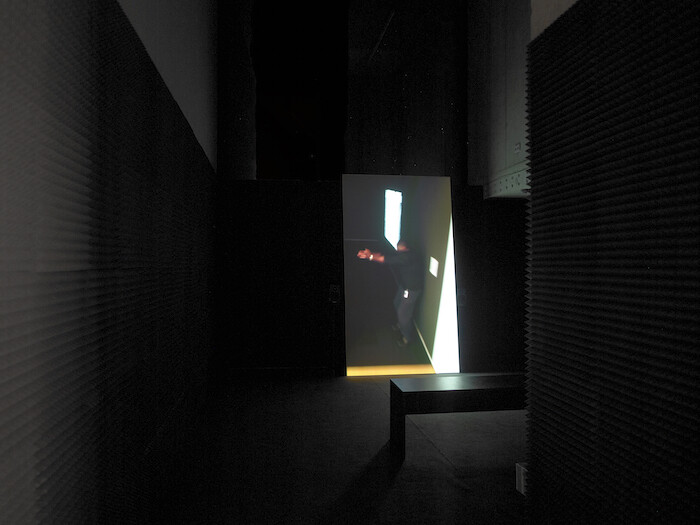

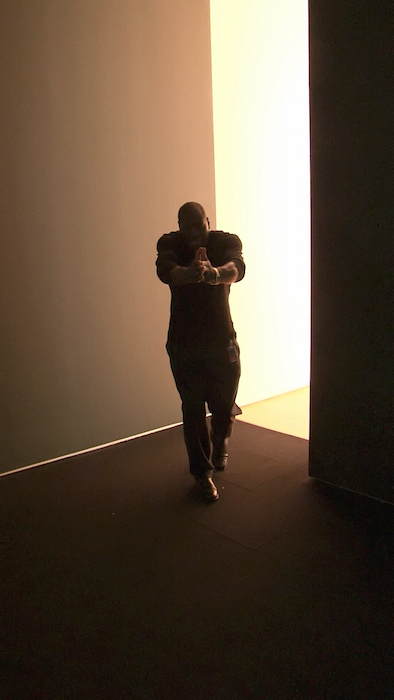

The museum guards who work for the Art Institute of Chicago are all African-American—a makeup indicative of the over-representation of the city’s black minority population in low-wage jobs. From the reports by head of security, Martin Whitfield, and fellow guard Ron Hicks, we can infer most are army or police veterans. Hicks demonstrates his trade and training by engaging in a haunting choreography. “I run my walls,” he repeats like a mantra. He will subsequently tell us the story of a young trooper who, after returning to the U.S. from Afghanistan, barricaded himself in his own apartment and committed suicide upon police arrival. While he speaks, Steyerl’s video quietly turns the museum’s De Koonings, Twomblys, Rothkos, and Richters into news feeds, displaying helicopter chases and combat troops. Much like the zone of privileged reception (the museum), the zone of privileged consumption (the West) requires constant patrolling.

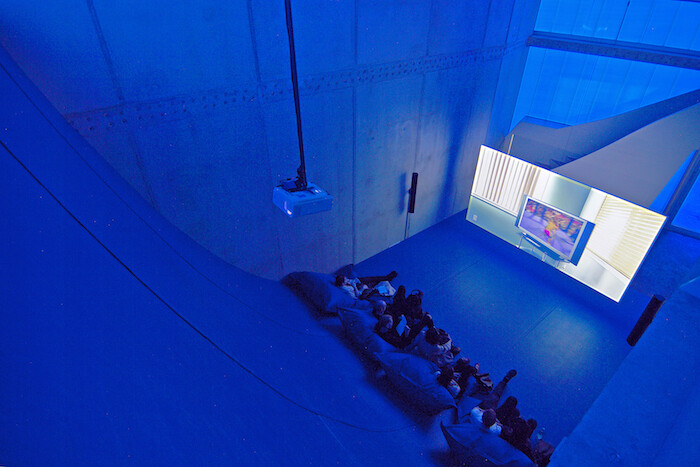

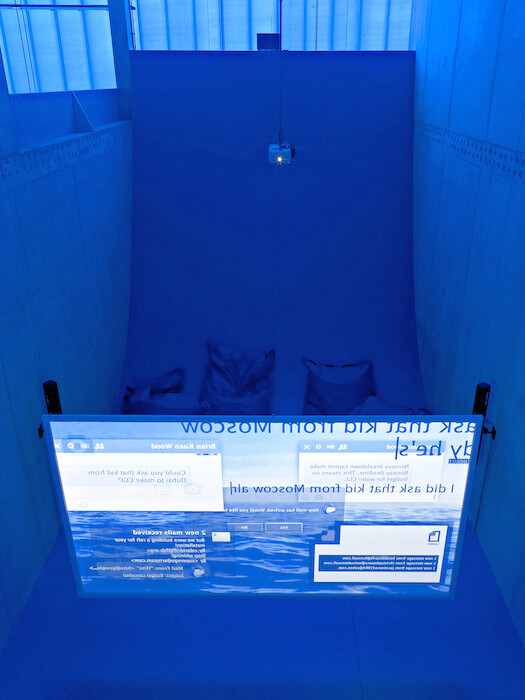

Guards is the oldest work on show at “Left To Our Own Devices”—Steyerl’s first commercial gallery exhibition in Germany—a survey comprising three video-recorded lecture-performances and the video installation Liquidity Inc. (2014), one of Steyerl’s best-known works. The video’s protagonist is Jacob Wood, a Vietnam war orphan brought to the U.S. under President Ford’s Operation Babylift,2 who grew up to become an investment banker. After the collapse of his employer, the investment bank Lehman Brothers, Wood reinvented himself as a wrestling-match host. The video’s title refers to Bruce Lee’s advice turned neoliberal motto “be water, my friend” (from the documentary A Warrior’s Journey, 2000). “You must be shapeless, formless, like water. When you pour water in a cup, it becomes the cup. When you pour water in a bottle, it becomes the bottle. When you pour water in a teapot, it becomes the teapot”—in other words: identity must be pliable to industry. Everything metamorphic can be seen as an analogue for currency. Liquidity, one could say, is the aesthetic ideology of transnational finance—the social form of post-democracy.

The universalization of precarity, which follows labor market flexibility and the modalities of identity this process generates, is also the topic of I Dreamed A Dream: Politics in the Age of Mass Art Production (2013), in which Steyerl recounts the wish expressed by a guerrilla fighter, Comrade X, to write a sequel to Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables against the backdrop of Susan Boyle’s rendition of Les Mis, the musical. Everyone wants to become an artist, not merely because art as a totalization of experience appears as the only possible antidote to labor as an alienation of experience, but also because within an economy of exceptionalism, there’s no other choice but to become exceptional.

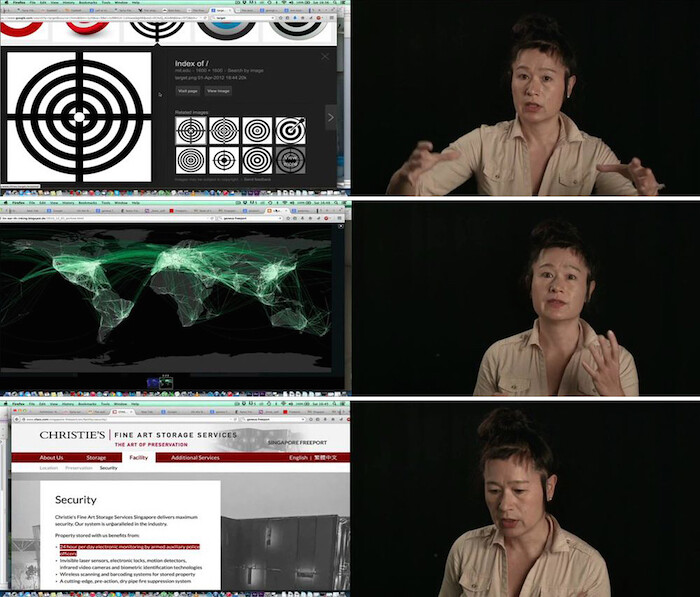

Art, it goes without saying, is exceptional in more ways than one. In Duty Free Art (2014) Steyerl tackles the juridical exceptionalism of artworks stored at the Geneva Freeport, an extraterritorial space, exempt from the jurisdiction of the local laws. For as long as artworks are stored there, they are exempt from import taxes and duties. If sold at the Freeport, they pay no transaction tax either. Their immobility, one could say, is the source of immense financial mobilization. There is also a striking equivalence with certain London apartment blocks, reportedly sold 16 times over before construction was ever finished. Much like real estate—also traditionally seen as an illiquid asset—art managed to become a conveyor belt for liquidity. But contemporary art is not just an asset. Radical aesthetics is often a substitute for political parity, as demonstrated by the Syrian regime’s wish to have a contemporary art museum built by star architect Rem Koolhaas (revealed in documents released by Wikileaks, quoted in the video).

The exhibition’s final work, Is the Museum a Battlefield? (2013), delves further into the entanglement between contemporary art and the arms industry. Andrea Wolf, Steyerl’s friend to whom she dedicated the video November (2004), was killed while fighting for the PKK (Kurdish Workers’ Party) by bullets manufactured by Lockheed Martin, the same company which sponsored the Istanbul Biennial and the Art Institute of Chicago, where Steyerl’s work was recently shown. But it would be unfair to reduce the exhibition to a denouncement of how contemporary art has been captured by capital. The relation between aesthetic and social forms has never been straightforward, but what Steyerl makes manifest is that art is always constituted by a practice, and that every practice constitutes a set of social relations. In other words, we are perhaps beyond the question of whether art can survive in a Post-Fordist world (it can); Steyerl’s quest would be to contribute to the transformation of this world.3

Jacques Rancière, “Thinking between disciplines: an aesthetics of knowledge,” in Parrhesia, vol. 1 (Summer 2006): 1–12.

Operation Babylift was the name given to the mass kidnap and evacuation of children from South Vietnam to the U.S., Australia and Canada on April 3–26, 1975.

The Hegelian question of whether art can survive in a late capitalist world, and the Marxist question of whether art can contribute to the transformation of this world, were famously discussed in Theodor Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory (1970).