Kader Attia’s current exhibition, “Scarification, Self Skin’s Architecture” at Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin, is the latest iteration of a project the French-Algerian artist initiated with his installation The Repair from Occident to Extra-Occidental Cultures, presented at Documenta 13 in 2012. That first iteration could perhaps be described as an essay in comparative aesthetics written from the vantage point of the wretched of the West. Juxtaposing the disfigured faces of World War I soldiers against broken fetishes, fractured African masks, or stitched-up pieces of loincloth, the project described a narrative arc from the practical notion of repair—redefined as the practice through which colonized cultures appropriate the symbols of the colonizing powers into their own cultural idioms—to the juridical realm of “reparation,” as in the replenishment of a previously inflicted loss.

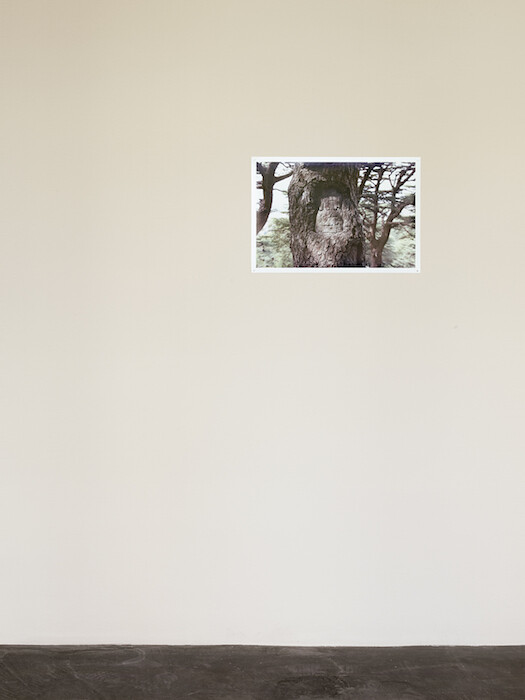

In “Scarification, Self Skin’s Architecture,” Attia returns to this dialectics of destruction and healing, this time through an inquiry into the at-times-material, at-times-metaphoric meaning of injury. The exhibition is staged upon and around a table, Self Skin’s Architecture (2015), surveyed by a wooden sculpture made by the Mahafaly (an ethnic group from Madagascar), severely scarred by horizontal splits. On the table, several photographs of African women with ritual scarifications on their torsos are aligned side by side with fragments of plates formerly used for illustrations in the Le petit journal, a French newspaper which was widely read in the late nineteenth century; a linoleum etching made in the DDR in 1966 that the artist found in a flea market; manifold hand-carved wooden printing blocks for textiles stemming from Bombay and Kashmir; photographs of relief elements in the architecture of Djenné in Mali; and a photographic detail of the bundles of rodier palm sticks embedded in the walls of its great mud mosque. On the adjacent wall is a small photograph of a tree trunk into which a message is carved, titled Scars have the strange power to remind us that our past is real (2015). The picture was taken by the artist near the site of the September 9, 1983 massacre at Maasser el-Chouf in which, during the Lebanese civil war, the Druze community targeted the Christian one. The message is clearly written in Arabic, yet the text is impossible to decipher.

Other than the play on the formal trope of negative versus positive, the assembled objects and images function as both a cipher for trauma and an allegory for colonial hierarchies. The title of the exhibition refers to French psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu’s concept of the “Skin-Ego.” According to Anzieu, both the Ego and identity are mapped onto the skin: the Ego provides the psyche with a protective envelope whose function is assimilated to that of a skin—part metaphor, part psychoanalytic concept—a force field of sorts, produced by the combination of olfactory, aural, oral, and other sensory factors. For Anzieu, the ego is an armor. In most traditional cultures, however, such as the African ethnic groups Attia depicts, the self is not autonomous but social, and it cannot be constituted without recourse to hetero-affective elements. The traumatic incisions produced by scarification turn the body into a human sign, fit to enter society and culture. But this reversal of inwardness and outwardness is not only a psychoanalytical play, it’s a political one.

In his 2002 book The Open: Man and Animal, Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben coined the term “anthropological machine” in order to describe the sorting machine that separates the “human” from the “nonhuman.”1 The anthropological machine is not, strictly speaking, a technical apparatus but an institutional one whose operations were set in motion by the racial theories of nineteenth-century armchair scholars, according to whom extra-occidental people are strangers to politics and history, living a life which is not fully qualified as “human” but belongs instead to stasis and nature. As the Cameroonian historian Achille Mbembe notes, “Africa” designates not only a continent, but the negative of “our” world, the opposite of everything civilized, orderly, and human: the very opposite of life.2 Africans are assimilated to bodies void of subjectivity, bodies that do not belong to culture but to geology, mapped onto mud or clay and marked with the same motifs and reliefs found in the vegetable and the mineral.

From this perspective, Attia’s syncretic collection, displayed in the guise of an ethnographic gallery, could be construed as a metaphor for who gets to sit at the dinner table, in which the operations of the anthropological machine are mapped onto German reunification or the Lebanese Civil War, pointing to how the policies that lead to the dismantling of state structures are always tied to the narrative of “failed states.”3 However, the rarefied atmosphere of a white-cube gallery—with the added difficulty of its function as a vast storefront—mutes the violence the exhibition alludes to, emphasizing the formal continuities between the disparate elements rather than the theoretical threads the artist conjures. But though it might lack the pathos of former presentations, “Scarification, Self Skin’s Architecture” is rather an iteration of an ongoing tour de force than a fully closed project.

Giorgio Agamben, The Open: Man and Animal (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004).

Achille Mbembe, Critique de la raison nègre (Paris: Éditions de la Découverte, 2013).

Ibid.