I was sent into darkness. I couldn’t see a single thing. There was a fuzzy light right behind the gallery door illuminating press releases laid out on a small table, and a gallery staffer equipped with a small flashlight. But she simply pointed into the dark: “That way.” That way was Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s exhibition “QM.15” at Esther Schipper in Berlin. That way felt like a ghost hall.

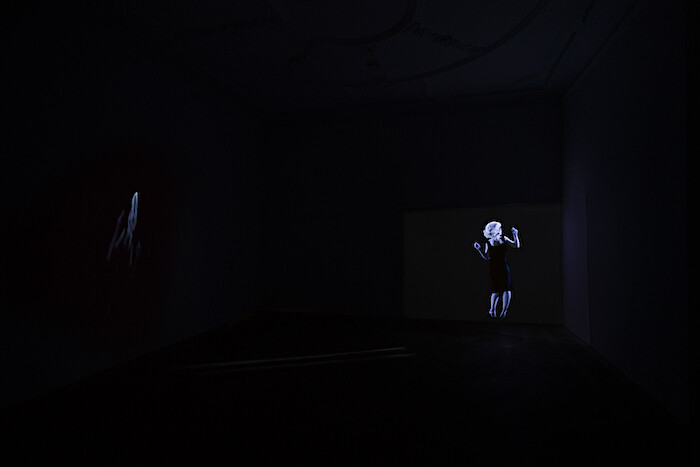

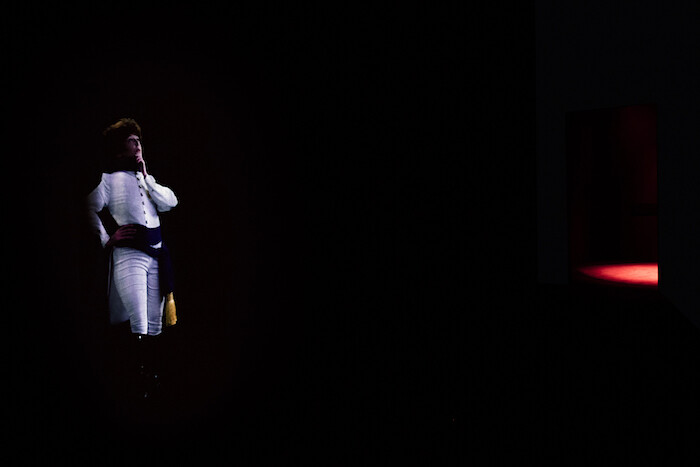

I heard a female voice singing an aria, but I had to pass by a life-sized moving image of a woman in a white uniform, fumbling my way along, before I fell over a rope that prevented me from reaching its source: an apparition of Maria Callas. A holographic illusion, to be more precise, of Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster playing Maria Callas: Opera (QM.15) (2016).

I don’t have a particular passion for being blindfolded. I hate ghosts, and I also hate costumes. A day before Halloween, Berlin’s Schinkel Pavillon organized an event for people who are, I guess, excited about these things: a costume party as part of an exhibition. Produced by the artist in collaboration with the Berlin fashion designers BLESS and design studio Manuel Raeder, “Costumes & Wishes for the 21st Century” could be considered an extension of the Esther Schipper show or vice versa. At Esther Schipper, Gonzalez-Foerster appears in three projections—in addition to the impersonation of Maria Callas, in Teatro (QM.15) (2016) the artist plays Sarah Bernhardt performing the Duke of Reichstadt, son of Napoleon, the lead role in Edmond Rostand’s 1900 drama L’Aiglon. In the third hologram, Cinema (QM.15) (2016), Gonzalez-Foerster dances like Marilyn Monroe in the 1961 film The Misfits, appearing, at least to my memory, alone in the countryside. At the Schinkel Pavillon, the clothes she was wearing for these roles—respectively a red robe, a white uniform, and a black dress—are laid out as art objects.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster first put herself literally in the shoes of such people as Scarlett O’Hara or Edgar Allen Poe in 2012. As part of the “Memory Marathon” at the Serpentine Gallery, she introduced well-known characters from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and engaged them in a discussion about the status of opera in our present times. Subsequent versions of M. 2062 were played out across different locations, of which M. 20162 (The Boy with Green Hair) showed at the Irish Museum of Modern Art of Dublin, in June 2013, and M. 2062 (Edgar Allan Poe) at the Palais de Tokyo, in December of the same year. Costumes from both performances are on display at the Schinkel Pavillon.

In 1998 the Museum of Contemporary Art of Los Angeles presented “Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949–1979,” a whole show dedicated to the presentation of clothes and performance props. At MoCA, as at the Schinkel, the whole spirit of those objects would have been perceived differently if viewers could have touched and used them. In order to allow them to do so, for the Schinkel’s costume party, a new set of clothes was designed.

BLESS came up with “wearable fragments of a silhouette, inspired by the costumes worn by Gonzalez-Foester in her apparitions,” as described in the exhibition text. These garments hung in the gallery’s basement, and visitors could dress up in one-legged-jeans, or tie red robe-rags around themselves with a white pearl belt. If this was meant to present the opportunity to feel the spirit of the artist’s experience as Marilyn Monroe or Edgar Allan Poe—“to incorporate the characters,” the invitation read—it failed. It rather felt like a ride into the local contemporary fashion world that art doesn’t need. The clothes can be purchased, and in that respect, I would even call it a joyful marketing strategy. The lines between private gallery space and non-profit institutions, between commercial and non-commercial zones, are very blurry, and every time an exhibition opens we can engage in this discussion anew, especially when artists themselves emphasize the relationship between market and art and play it out aesthetically.

The artist originally presented the Esther Schipper performances in what she calls a “triple apparition” live in a theater-like space at Centre Pompidou in January—Sarah Bernhardt becoming Marilyn Monroe before turning into Maria Callas. At Esther Schipper, walking among the holograms was like witnessing imitations of moments of artistic glory, even joining a woman struggling with her own destiny. Glory passes, and few remember.

Gonzalez-Foerster is not the only artist to have engaged with the dead. Françoise Sagan was equally fascinated by Sarah Bernhardt, to whose ghost she addressed a letter, which Sagan then answered herself. The correspondence, published in 1988 as Dear Sarah Bernhardt, a sort of epistolary biography, is a journey through Bernhardt’s life from the coffin where she presently lays to the theaters she once lived in, a journey that transforms history into fiction, and fiction into history.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster takes a similar, yet slightly different path. She does not address history outside of fiction. She only addresses the fictional personas of three female artists, isolating the roles performed in the theater, the opera, and on the cinema screen, and animates them in the art space. In this regard, the exhibition is not only an homage to the artists and the arts; it provides them with a safe house in the exhibition space. It is worth protecting that, even when you have to step into the dark in order to do so.