A heady gallery opening experience last October found a few scattered souls humming to themselves in a series of empty rooms. At that same gallery one month later, a man performed a pantomime of sorts on invisible strings. Standing over a block of wood with a radio antennae sticking out of the top, hands like marionettes, either he controlled or was controlled by the spooky sounds coming through the loudspeakers, providing comic relief for a town otherwise known for its techno. These two independently curious productions—by Olaf Nicolai and Annika Eriksson respectively—were orchestrated by Clara Meister, the curator ringmaster of music experiments in Berlin these days. Through the collaborative project Soundfair, Meister commissions artists to participate in the performance series “Symphony,” held sporadically at VW (VeneKlassen/Werner) over a period of 6 months. “Symphony,” thus, invites artists to step into the skin of a musician and, likewise, musicians to step into the bubble of a gallery space for an evening.

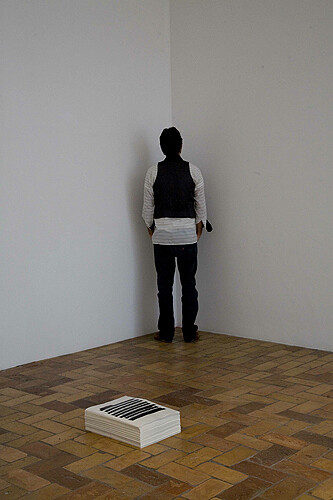

So to better clarify: Olaf Nicolai’s disparate hummers were not your usual repressed neurotic whistling types. They were performing, in all seriousness, Romanticist Robert Schumann’s direction to the musician, in-between the staves of his “Humoresque Op 20,” which reads, “innere Stimme” (inner voice). This is similar to asking the piano player to invoke the powers of his third eye, mid-concert: a silent impression kept secret from the audience. Olaf’s changing cast of performers translated this “inner voice” into their own invented hum and hymnal for the following 30 hours, as they walked freely around the gallery, enacting Schumann’s Augenmusik (eye music) so to speak. Unfortunately, few saw this invisible phenomena made audibly and physically present: imagine an otherwise empty gallery with a single man humming to himself in a corner or a lady circling the room with her melancholic vibes.

Many were familiar with Annika Eriksson’s minimalist tactics, with her film Wir Sind Wieder Da (2010) having only recently been shown locally at the daadgalerie. In this single-take film, a group of punks loiter on a bunch of dirty, outdoor couches, drinking beer in the atmospheric night fog, far from the subversive semiotics of the imagination. It was as if she had just filmed a “found situation.” Ergo, it was in great anticipation of “found-sound” that Eriksson’s surprisingly more classical performance unfolded at VW. The eerie sounds produced were based on a song composed in 1929 by the “Karl Marx of Music” Hanns Eisler (with text by Bertolt Brecht) whose protest hymn “Forwards and Don’t Forget” was re-composed by Eriksson for the theremin, an early electronic instrument played by interfering with its magnetic field by waving one’s hands around it. The clever wordplay of the piece’s title “The Plan Was Sound, the Execution Faulty” didn’t hit until later, when the whole phrase suddenly turned on its head—as if Communism were alive and well despite the regime’s attempts at damnatio memoriae.

Both of these performances could be seen as Solidaritätslieder, forms of “Give me your tired, your poor”: commands to leave the LED screen, or, like John Lennon and Yoko Ono, to get into bed for more than late-night updates on protests in the Middle East. Listen to your “inner voice,” that is, instead of looking for the reaction of the huddled others, alone in their dark rooms, lit up by an electroluminescence and seemingly commanded by its reflected bluish hue.