This is a silent party. Many guests have come here to celebrate the spring equinox. Spirits and things are freely circulating in the space. This is how it feels when entering Özlem Altin’s exhibition “Cathartic ballet” at CIRCUS. All is still, a perfect silence, yet something is happening.

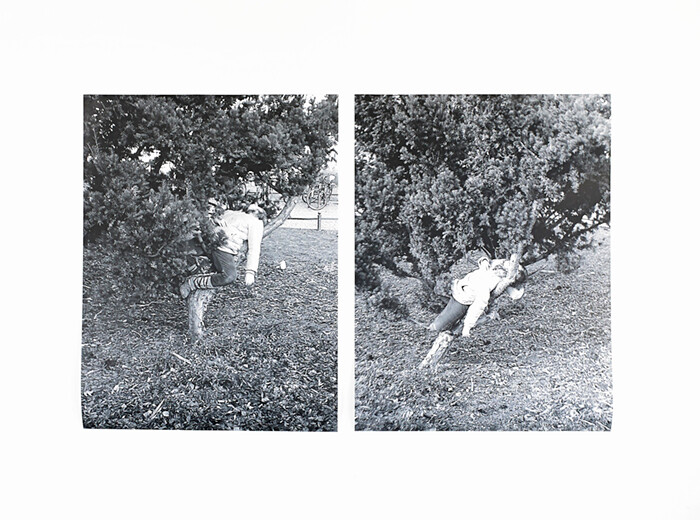

At the entrance, the first “guest” you meet is Untitled (Mädchen im Baum) (2013), two black-and-white photographs of the body of a woman entangled between the branches of a big tree. Her legs clasped around the trunk, the head bent over, the torso stretched out as if in a gymnastic exercise. The images capture the figure from two different angles, two reverse perspectives: front and back. Rest and exhaustion. Comforting and disturbing. In this unnatural pose, hooked onto a tree, the figure looks like an abandoned object, her body torn like that of a broken doll. A doll on a tree like a body as a thing amongst things. It produces a sense of estrangement-empathy.

Altin has transformed the neutral space of the gallery into a place crawling with doll-like humans, human-like gestures, objects-like-poses, and bodies-like-rhythms that respond to each other and perform in synch to set the whole space in motion. Everybody is caught in action here: upon entering the space, you realize that at this party we all become guests and hosts to one another.

Engaged in an ongoing conversation, you find yourself literally and physically in the middle of it; surrounded by familiar faces and abstract presences. Untitled (holding your arm or leg) (2013) is a collage painting of an uncanny figure against a dark background with an egg-shaped body to which the artist has applied human legs or arms. Looking at it, it feels as if those legs/arms are moving in response to an upsetting comment made by the figure opposite, whose familiar face makes you feel that you have been invited into a conversation that has been going on for a while. It’s Untitled (Hannah) (2013), a lithoprint black-and-white portrait of Berlin Dada artist Hannah Höch. Sister spirits. The enigmatic look seems to be part of a triangulation, which also includes Belonging (restless attachment) (2013), an abstract portrait of a figure whose darkened face appears to be literally lost in space (of the canvas, in this case). As the contours of her face fade, a yellow light radiates from the center of the painting, which it is also the center of the face. The portrait of a thoughtful person must look exactly like this, a particular combination of color, space, and rhythm.

The works in the exhibition speak a language that could at times be read as opaque and mysterious. Yet, one can use language to communicate. One can also be in language and fully embrace its moments of opacity. The uncanny figures that populate Altin’s photos, collage paintings, and installations mimic, inhabit, and embody language.

To be in language is also a dirty affair. The collage paintings are made of partial, roughly torn, found images like Staring Back at him (2012), in which a dark, roughly painted figure with two applied mismatched eyes enigmatically stares back at a figure opposite in Whispering hands (2013), a lithoprint of a found image, which shows a man holding his head in a gesture of desperation, exhaustion, or extreme concentration. The juxtaposition of the same image but slightly skewed in the repetition complicates the reading of the man’s gesture. Is he desperate or is he voguing? Certainly, he is passionately engaged in something, perhaps rehearsing his part in the choreography for the ballet.

The collage, paintings, and installations in “Cathartic ballet” are like fragments of an unspoken conversation. Yet the silence of the exhibition is not metaphysical, not one of secrecy. It’s the silence of things that speak.