“At present,” everything is at steak [sic].

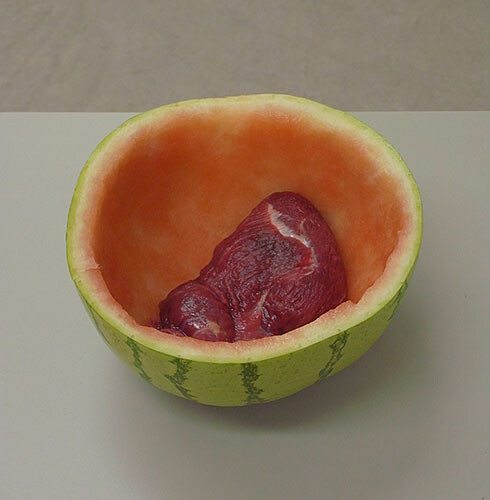

“One must dance until the music stops,” to quote the sentence made famous by a Citigroup manager in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008. The music, however, had long since stopped when he said it. There is a similar after-party feeling to Bojan Sarcevic’s “At Present” show at BQ gallery, Berlin. In an otherwise empty room, one finds a slab of steak inside a hollowed-out watermelon, like the leftovers of any given barbecue, hallowed atop a minimal plinth; and a photograph of a white Daihatsu Charade parked on a snowy street, with a PALESTINE decal in the rear window.

Are these downtrodden objects meant to symbolize a downtrodden people? Is the piece of meat an allusion to the “bare life” of the stateless Palestinians? Maybe. But the small Daihatsu Charade is not the only riddle in the room, and the divested state of the objects on display stands in stark contrast with the dynamism of the artist statement, which one finds near the entrance in lieu of a press release. With a series of open-ended questions, Bojan Sarcevic asks if we live in the most conformist phase of modern history, whether there can be any protest, which is not readily co-opted, and why is it that conflict is vanishing even though exploitation is rampant. The statement is displayed underneath a poster whose image is composed of a repetitive pattern, namely, that of the returned-to-sender postcards bearing the stamp of the Palestinian Authority: the invites to the show, sent out on 20 August 2011 from a post office in Ramallah, that never reached their addressees.

Incongruous as it all may seem, Sarcevic’s work has always oscillated between autonomy and contingency. In former films and installations, the artist has shown stray dogs wandering inside a picturesque Dutch church (It Seems that an Animal Is in the World as Water in the Water, 1999); Designer clothes worn out by car mechanics with all the signs of wear and tear (Worker’s Favourite Clothes Worn while S/He Worked, 1999-2000); collages in which images of architectural interiors are cut-out into star polygons and polyhedra—little mathematic marvels—subsequently glued back on to the original pictures as disruptive whirls (“1954,” 2004); or wondrous animations made out of such trivial everyday objects, such as scrunched paper and tree branches (in the film series, “Only After Dark,” 2007).

“I see these pieces as actors,” Sarcevic is quoted as saying in a Frieze article about his tree branches and scrunched up paper, and one can certainly recall the steak that starred in one of his previous film productions (“Only After Dark”). Yet the miniature sculpture park in these phenakistoscopic-like images never exists outside the flickering domain of film, and its conflicting motifs—geometrical and ornamental, repetition and uniqueness—unravel in a flurry of shadowy effects. In “At Present,” the motion that animated previous works comes to a grinding halt. The luminous, phantasmic, space of the film becomes the geopolitical axis West Bank/Gaza-Berlin. Its actors—steak, watermelon, photograph of a car, and postcard poster—acquire the fixed, mum, quality of stage props.

The dilemma of “At Present,” how to find one’s own position, becomes the dilemma of its viewer. Meaning demands closure. Faced with the threat of dissociation one struggles to find a cognitive synthesis. The ancillary text is ripe with expressions of frustration with the lack of historical movements, yet the show’s open-ended approach might hint at a fundamental stasis in the epistemology of the twentieth century: the semantics of modernity crucially depend on the kinematics of modernity. Capital and labor, labor and leisure, welfare and profit, sovereignty and occupation, left and right, social democracy and financial markets, debt and credit can only subsist while the music plays on—yet we are all running out of spare change for the jukebox.