Born in Vietnam but raised in Denmark, Danh Vo is a “man without qualities.” “What he thinks of anything will always depend on some possible context – nothing is, to him, what it is; everything is subject to change, in flux, part of a whole, of an infinite number of wholes presumably adding up to a super whole that, however, he knows nothing about.” (Robert Musil). Or, as Vo himself put it, someone who sees the use of things when he can’t find the meaning in them.

Vo became known through a number of maverick projects. For his solo show “Not a Drop but the Fall” (2005) in gallery Klosterfelde, Vo duped both the Danish Art Council and his former boyfriend Michael Elmgreen into unwittingly supporting a fake application. Under the name of the famous art-duo Elmgreen & Dragset, he received funding to travel to Marfa, Texas, and document the opening of their Prada shop project, which he later showed together with the scam’s paper trail. In the ongoing project Vo Rocasco Rasmussen (2003-) Vo married and divorced several people in order to accumulate a succession of last names intended to bewilder customs’ officers.

For his graduate exhibition, Vo asked his family to actually “do” the show for him. Common to all of the above is a certain form of deceit, in view of what ought to be the “proper” way to proceed, along with a savvy subversiveness. The school’s staging of authorship crumbles under the comic cliché of the Asian family as a working unit; institutionalized tolerance gets flipped into control.

In the staged clash between bureaucracy and biography, the dismaying outcome is not that bureaucracy might impair biography but that biography is an effect of bureaucracy. Though it is true that a marriage marks a relationship between two people and the state apparatus, it remains nonetheless so that “marriage” provides the mold for all other monogamous, i.e., committed, love affairs, whose rules obviously include not duping your partner into signing fake papers, so you can follow him to Marfa. Danh Vo doesn’t believe in personal history though. All identity is a matter of cultural artifice, and being Vietnamese, gay or a refugee, have no intrinsic meaning. Which is not to say they are of no use: the artist’s sleight of hand is in finding the added value in the cheeky use of it all, be it family, gender orientation or ethnicity.

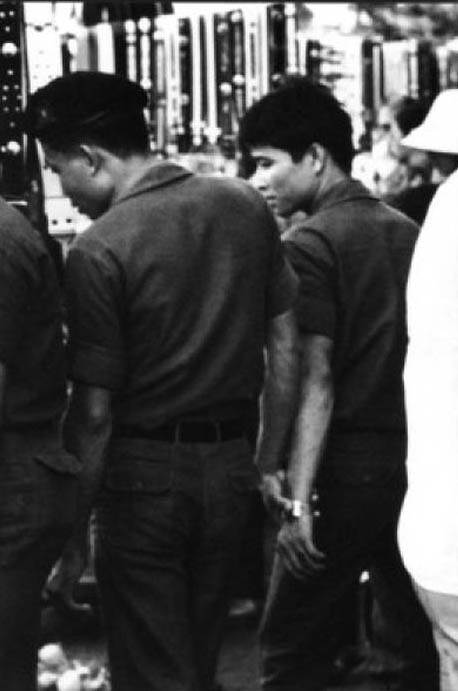

Charmingly light-hearted, as all of these early projects might have been, Vo has, however, found his way into darker places. Out of a serendipitous encounter with an elder American named Joseph M. Carrier, Vo came into the possession of an assortment of items – diaries, documents from the RAND Corporation, love letters detailing encounters between American soldiers and Vietnamese boys, and heaps of photographs – from which, since “fiction is often the best fact,” he fancied as his own biographical narrative. In “Good Life” (1966/2007) Vo exhibited a collection of photos of young men holding hands: a trivial act which only acquires an erotic connotation when seen through the lens of Western rules of public displays of affection. For the Stedelijk Museum’s show “Package Tour” (2008) Vo displayed his late grandmother’s grave marker together with his father’s Rolex watch, Dupont lighter, and signet ring. In the last Berlin Biennial the same objects were shown along the last letter the missionary Théophane Vénard – later canonized by Pope John Paul II – wrote his father, before being decapitated. In his own open-house studio the public could contemplate Vo’s floral bathroom tiles, printed out of the botanical drawings of Jean-André Soulié, who was tortured and executed in Tibet in 1905. Nostalgia is a modern disease, and under the pressure of deterritorialization the loss of a topographical belonging gets projected onto a temporal void, embodied by objects of times past. Whether its Vo’s disease or ours he won’t disclose.

For the current show at Isabella Bortolozzi, “All your deeds shall in water be writ, but this in marble,” we re-encounter Vénard’s letter hand-copied by Vo’s own father, along with the information that the title and numbering of existing copies will remain undetermined until the death of the calligrapher Phung Vo. In the otherwise vacant gallery space – whose somber atmosphere the show appropriates – Vo installed a black marble tombstone with carved golden text reading, “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.” The sentence is taken from the poet John Keats’s tombstone, which Keats himself is thought to have taken from Beaumont and Fletcher’s early 17th century play Philaster (“All your better deeds/ Shall be in water writ”). The tombstone is intended to mark the grave of Phung Vo, upon whose death it will be moved to Copenhagen, though remaining in the possession of whomever chooses to buy it. Ancillary to the show, Vo engraved a brass plate with the floor plan and works on display.

To extend a claim of authorship to the domain of the immaterial has long been the strategy of contemporary art, from Bruce Nauman’s gestures to Tino Sehgal’s talks, Vo, however, exceeds in formal closure. He extends the domain of property –transcendental property but property nonetheless – to such unfathomable reigns as bereavement and loss. To say that his elegant, detached objects are cold-blooded falls short of understanding their meaning. To say they are poetic is nothing but a platitude. The nonplussed feeling that arises in his work partakes in what we might call the intuition of something supra-personal, though, to paraphrase Musil, “the affinity and kinship of the things that meet inside one’s head is in reality only something non-personal.”