There is a problem facing the history of media: that time can not be represented independently of the technologies of information. We cannot simply write a historical account of technical inventions, because these inventions themselves structure the temporality of events and processes in our world. This is, at least, according to the adherents of media archeology, which, recently, with the appearance of English translations of the work of the media theorist Wolfgang Ernst, has gained some popularity.1 Using a combination of Foucault’s early writing and media theory, media archeology strives to literally excavate rusted and scrapped parts of computers, radios, or other gadgets—though not from the soil, but from dusty archives and collections of old machinery. Very much like real archeology, media archeology comes with a type of mysticism that positions the archaeologist as an adventurous time traveler. The expression Gleichursprünglichkeit [simultaneous originality] points to the idea that the origins of a technology are inscribed and remain present in it, as if the moment of invention would forever exert its structuring force.

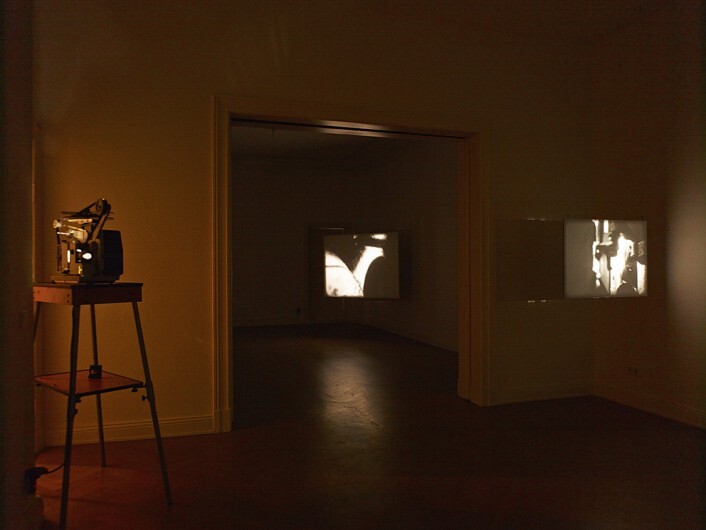

“Let The Body Be Electric, Let There Be Whistleblowers,” curated by Heidi Ballet and Anselm Franke, gets as close to the mysticism of media archeology as can be. As one enters the gallery space, one hears a familiar sound: the rattling of the film projectors which have, in the cinema’s post-celluloid age, returned for a second life in contemporary art. Throughout modernism, the art world fancied the re-appropriation of outdated technologies—at times nostalgic, at times market-driven. The cinematic apparatus is just one of very many examples of that which has been re-appropriated, starting with painting itself.

Recently, artist Hito Steyerl expressed her resentment towards useless cinematic gadgets in gallery spaces: “Next time I see another 16mm film projector rattling away in a gallery I will personally kidnap it and take the poor thing to a pensioners home. There is usually no intrinsic reason whatsoever for the use of 16mm film nowadays except for making moving images look pretentious, expensive and vaguely modernist, all prepackaged with a whiff of WASPish art history.”2 Some artists’ use of noisy projectors is intrinsic to their practice, like Rosa Barba making it a characteristic feature of much of her work, or Simon Starling in his piece Wilhelm Noack oHG (2006), that lets the film strip run through a sculptural spiral structure whose fabrication is documented in the images. But even this inherently well reasoned noise tends to look like a fashionable display of a nostalgic admiration for old media.

Three 16mm projections by Joachim Koester across two rooms produce most of the exhibition’s noise. The film HOWE (2013) shows close-ups of a sewing machine in motion. Its title refers to the first machine of its kind invented by Elias Howe, which was patented in 1846. Of Spirits and Empty Spaces (2012) deals with a weird account of a spiritual machine constructed by a former priest of the Universalist church. In 1853, John Murray Spears retreated from his church service, engaged in spiritual exercises, and claimed that messages would lead him to the construction of a machine called “The New Motor.” In 1861, Spears organized a series of spiritual séances that were supposed to make the participants part of an imaginary machine. The film animates a written dialogue of the worker’s meeting in their different roles, as the integralist, the implementer, the needlist, and so on. Some historical accounts claimed that the real machine was built and worked, albeit feebly. Others say it never really made a move, but was beautifully constructed.

The 16mm rattling is not the only loud sound in the gallery. Ken Jacobs’s video Let There Be Whistleblowers (2005) is soundtracked by a rather speedy performance of Steve Reich’s piece for two drummers Drumming (1970–71). The video presents a short sequence of movie stock from the early twentieth century: it shows trains arriving and departing. Since the Lumière brothers’ L’arrivée d’un train à La Ciotat from 1895, there has been no other more emblematic image for the beginnings of cinema. Trains and cameras were symbiotic technologies. Images of trains kept reappearing during early cinema to a degree that they formed own sub-genres of short movies. Jacobs’s work manipulates the footage of the coming and going trains, guiding the viewers’ gaze from the train’s interrupted movements to the gestures of single bystanders, maybe blowing a whistle, to visual shutter effects, metaphorical of rapid rotation.

Meanwhile, Alison Gibbs’s 16mm projection How to wash your hands in molten metal (2014) shows a sequence of hand gestures corresponding to a numerical code that dates back to the Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli (1445–1517), and was used in early bookkeeping. Green and yellow fingernails appearing from opposite sides apparently refer to the transactions of the artist’s bank account.

Finally, in Body Electric (2014) Koester delivers the urgently necessary reason for the rattling. The images of the silent film strongly resemble HOWE, almost as if based on the same footage. But instead of a sewing machine, we see close-ups of a 16mm film projector in operation, a perfect example of applied media archeology. This point closes a circuit that turns the whole show into consistent display of a technicality at work, with all its mystical ramifications.

Wolfgang Ernst, Digital Memory and the Archive (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Daniel Rourke, “Artifacts: A Conversation between Hito Steyerl and Daniel Rourke,” Rhizome (March 28, 2013), http://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/mar/28/artifacts/.