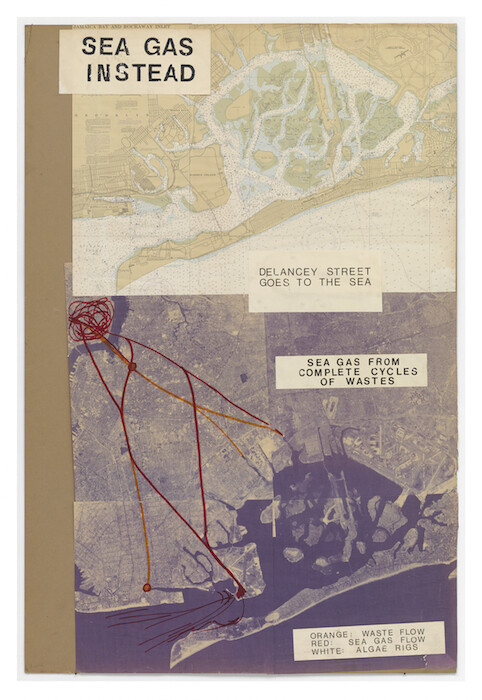

At first I had the feeling I was missing something when I encountered the documentation of unbuilt works by Peter Fend at his show “to be built” at Galerie Barbara Weiss, organized in collaboration with the project space Oracle. The drawings, prints, collages, and documents on display, mostly from the first 20 years of Fend’s practice, are billed as projects meant “to be built,” but if they’re really instructions, they’re hard to follow. For example, Delancey Street goes to the Sea, II, III, and IV, a series of quite beautiful collages from 1979, declares “CON ED / NO MAJOR GAS LINES DOWNTOWN,” with text overlaid on an aerial shot of lower Manhattan, followed by “SEA GAS INSTEAD,” the proposed solution. Red and orange lines drawn over the image demonstrate how waste pipes could be extended from Delancey Street across Brooklyn and into Jamaica Bay, and sea gas could be sent back again. Sounds like a good idea. But how, exactly, would sea gas get made from the waste? Could you really lay a pipeline in a straight shot across an entire borough? Who would finance the project? Wait, what’s sea gas again?

Fend is probably best known for his founding role in the Ocean Earth Development Corporation, a collaborative initiative established and legally incorporated as a company in 1980 with Colen Fitzgibbon, Jenny Holzer, Peter Nadin, Richard Prince, and Robin Winters. The title of the group refers to the ocean both as an abundant natural resource and as a metaphor for fluid ownership and de-territorialization. Ocean Earth’s starting concept was to push Land Art earthworks beyond aesthetic engagement with the landscape towards actual intervention in ecological systems.1 Long before the Anthropocene became common parlance in the culture industry, and long before “speculative design” became a somewhat recognizable field, Fend was devising highly creative, collaborative, vast-scale ideas for ways to address impending ecological crisis.

The energy, if not the specifics, of those early ideas comes across in “to be built.” The show is like a retrospective-lite; neither exhaustive nor tightly focused, it presents the main themes and formal vocabulary that have persisted with surprising continuity in Fend’s work until today, with an emphasis on the way the work has been (self-)historicized. In this framework, it’s possible to recognize the profound influence Fend has had on a generation of younger artists engaged with similar topics, from Tomás Saraceno and Tue Greenfort to Simon Denny and Daniel Keller.

A plexiglass panel hangs in front of the first wall that the viewer encounters, museologically displaying documents: a typewritten essay from 1976 by Fend entitled “Agriculture Ends, Art Takes Over;” a mysterious pencil diagram of waste cycles; news clippings and press releases detailing Ocean Earth’s activities; and a selection of Fend’s now-well-known “word stacks”—sparse, concrete-poetry-like arrangements of text on paper. Linguistically evocative, the word stacks may be the most effective standalone pieces in the show. While they are provocations for action, they are also self-supporting aesthetic constructions that don’t rely on a forecasted external action to take effect in the exhibition context.

Some of the most recent works presented belong to the RAPID project, which Fend and collaborators began in 1999 under the group name “Rapid Response.” They proposed a “post-petroleum” gas station that would serve alternative fuels like methane at the pump. The five-letter RAPID logo is displayed on a lightbox on the gallery’s entrance facade (RAPID Logo, 2000), successfully branding the exhibition in an act of corporate mimicry; inside the gallery is a light-up object resembling a gas pump (RAPID Methane Gas Station, 2000).

Also on display is an Art in America review of an exhibition by the group at American Fine Arts, New York, in 2000, in which Cathy Lebowitz wrote: “Whether or not Rapid Response is able to build artist-designed alternative-fuel stations, the exhibition was successful in presenting an imaginative and in-depth look at concerns that affect everyone.” When I met Fend coincidentally at the exhibition, he said that, to him, this is precisely what qualifies his unbuilt projects as failures. RAPID wasn’t just meant to provoke thoughts. It was meant to become a functioning gas station.

Fend’s longstanding ambivalence about means and ends, compounded by his ambivalence in relation to the art world apparatus that manufactures things like career retrospectives, in this case may have disallowed him from diving headlong into the aesthetic challenge of displaying objects in space, so resistant does he seem to the imperative to do so at all. In this context the art(ifact) itself is left in an odd position: is it illustration? Advertisement? Mere byproduct? And then if the “real” plans are never implemented, doesn’t the artwork revert to being the real work by default?

While Fend’s designation between art world and real world is meant to imply that art can intervene in the structures of power in which it is already entangled rather than recirculating in a hermetic field, it also effectively places art that occurs solely inside the confines of the space of display futile, perpetually on the other side of the “real” divide. Rather than art only gaining political power when it reaches beyond its field, can artworks shown as a means to their own ends not likewise have some kind of agency? I’m inclined to say yes for today, but, thinking back to Ocean Earth, I’m not sure about tomorrow. As Fend continues to remind us: that question itself might become null when we’re knee-deep in melted polar ice caps.

Peter Fend has called this strategy “Applied Land Art.” He wrote in 2001: “Ocean Earth was specifically conceived as an instrument for implementing the goals of the environmental art movement, building upon the ideas of artists such as Robert Smithson, Dennis Oppenheim and Gordon Matta-Clark.” Peter Fend, “H2Earth,” Mute vol. 1 no. 22 (December 2001), http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/h2earth.