When the 7 percent value-added-tax rate on fine art went up to 19 percent in January 2014, it spelled to many the end of the Berlin art world. Proclamations followed that the market would dry up, and collectors would scatter to more cosmopolitan locales with less pricey export taxes. Without patrons or a steady stream of capital, how could Berlin’s artists thrive? The sheer volume of the jam-packed 2016 edition of Gallery Weekend Berlin suggests that the German capital’s art market is healthy as ever in its upper echelons, especially given the pricey 7,000-7,500 euro gallery participation fee, though younger galleries, perhaps hit hardest by the VAT rate update and who have largely figured these new expenses into the prices of their offerings, have seemingly responded with conservatism.

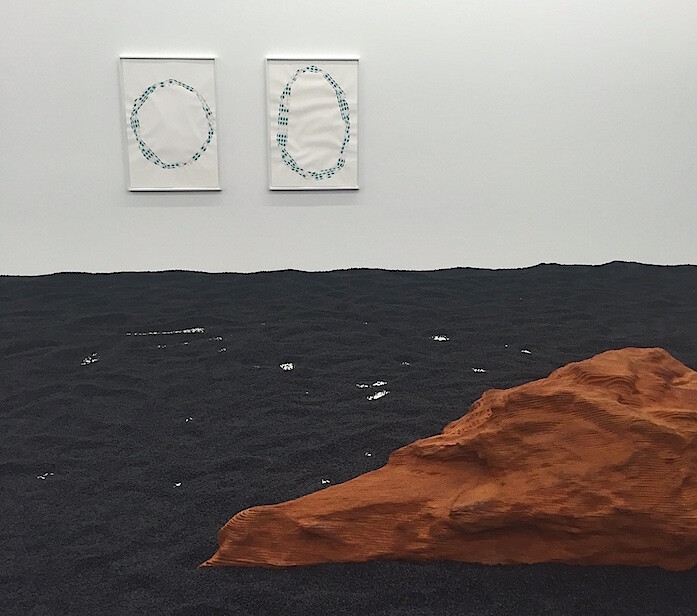

Two outliers to this trend are Aleksandra Domanović’s “Bull Without Horns” at Tanya Leighton and Alice Channer’s “Early Man” at Konrad Fischer. Domanović’s exhibition fills both of Leighton’s galleries, and includes her now-iconic sculptures featuring the Belgrade hand. Most unique in this exhibition are her new portraits of bulls that have been genetically modified to prevent them from growing horns. The large-scale, documentary-style photographs come off as earnestly tacky in a way that, somewhat paradoxically, knowingly rejects any aesthetic associations with the dominant artistic discourse in Berlin, to which Domanović’s practice has been integral. Alice Channer’s “Early Man” at Konrad Fischer dumps two tons of black polystyrene granulate microbeads (technical term “nurdles”) on the gallery floor, creating a black alien landscape which is dotted with rust-colored 3D-printed rocks. As the black nurdle sand is incredibly slippery, viewers become hyperconscious of their bodies navigating the gallery. Channer refers to this work, titled Burial, as a sculptural object rather than an installation, and thinks of her rusty Martian boulders as ciphers for a body. The body presented here is a horizontal one—perhaps an animal, or a human that is buried, as the title suggests. Channer’s use of nurdles, which are found in organic beach sand as unfilterable ocean trash, further suggest a poetic reconsideration of the delimitation of bodies, as the porousness of skin constantly absorbs its environment.

In the same Kreuzberg building, Żak | Branicka presents work unearthed from the KwieKulik archive—one of Gallery Weekend’s two outstanding historical presentations of underappreciated artists, the other at Exile, featuring Verena Pfisterer. The title work at Żak | Branicka is KwieKulik’s “Monument Without a Passport,” a series of photographs mounted to the wall in cinematic fashion. They tell the story of the artist duo declining an exhibition invitation outside of Poland amidst the country’s communist rule and closed borders, and the performance Kwiek and Kulik made in response. While the work could be read as exceedingly specific to its historical moment, the notions of artistic freedom and mobility seem like incredibly timeless and prescient subjects. An eponymous 2011 documentary on KwieKulik screened nearby at fsk-Kino as a complement to the exhibition at Żak | Branicka. The film provided an enticing look into the daily lives of Przemysław Kwiek and Zofia Kulik, who, living in separate houses on the same lot, bicker in an endearing way only longtime artistic and life partners could, and who have in recent years recommitted to working through and presenting the KwieKulik archive since disbanding in 1987.

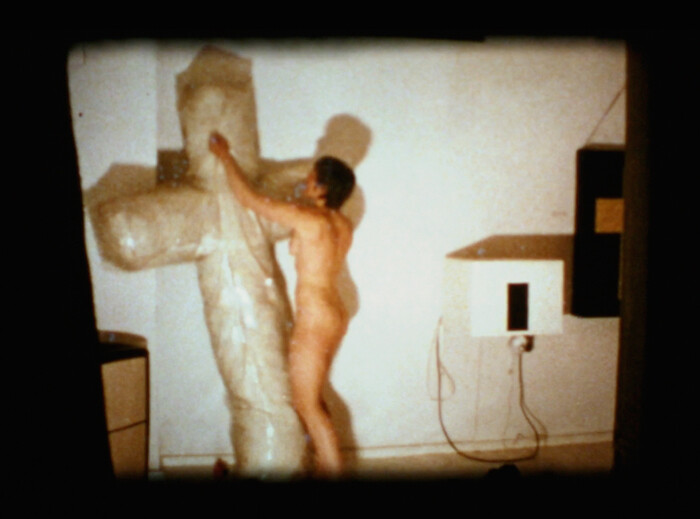

Verena Pfisterer’s installation at Exile, titled “Aktionen an Arbeiten von Verena Pfisterer,” was a surprisingly engrossing introduction to the work of this largely forgotten and incredibly idiosyncratic artist. Deceased since 2013, Pfisterer grew up in the small conservative town of Fulda, in central Germany, and attended the Städelschule, in Frankfurt. Though she worked in proximity to many artists who were brought to the market via Art Cologne, Pfisterer, like many women artists of that era, was erstwhile not successful with sales. She focused rather on creating ritualistic works using religious imagery that must be enacted by a viewer. On view at the gallery are both her static sculptural objects and the Super 8 documentation of their enactment transferred to 16mm by the artist. In one action (Rosa Kasten mit Stoffkreuzen, 1970), she stuffs colorful handmade plush toy crosses into the cross-shaped opening of a vaginal red plush box, appearing akin to a perverse children’s game. In another (Schlappi-Kreuz, 1967), she undresses and unhooks a body-size crucifix made out of what appears to be a mattress from being attached to the wall, and wraps her body around it as in embrace. It seems as if Exile is almost singlehandedly reviving the work of this sadly underknown artist.

Elsewhere, blue-chip artists were doing great things, not necessarily in blue-chip spaces: Rachel Harrison installed a homemade gym and a series of vibrantly colored, fitness-inspired sculptures in Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler’s office-building gallery space as well as in an adjacent conference room. FCHEM (2016) installs in the gallery’s main space a homemade gym festooned with gymnastic rings. Nearby sits a fitness ball slathered with brightly colored orange cement. Across the hall finds smaller works sat on a large conference room table surrounded by chairs. These playful works, such as a box filled with fresh white towels like those you’d see at the gym (Towels, 2016), bring to mind the strange proclivity of fitness companies to brand and sell intangibles like endurance and performance. Considering that Harrison is inarguably one of the most important sculptors of her generation, it comes off as winning and kind of punk that she would present such a confident yet playful show with an increasingly relevant young gallery such as Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, whose roster of artists borrow from Harrison’s aesthetic innovations that frequently feature mass-produced objects.

At Buchholz, Wolfgang Tillmans’s exhibition of photographs of beautiful young bohemians, sublime empty post-industrial spaces, and poignantly lit plants that manage to survive despite not being nurtured, were breathtakingly beautiful as is par for Tillmans’s course. Perhaps a more momentous effort from Tillmans is the recent change in programming at his project space Between Bridges. Since April 14, the space has been host to “Meeting Place,” a project founded in response to feelings of futility regarding the refugee crisis, which “wants to be a forum, however small; a platform, however powerless, to discuss and organize activity from within the art community.” The current exhibition, “Tour of Syria” is a series of photographs of Syria before and after the rise of ISIS, which have been largely printed out from the internet as a thought experiment by Syrian refugee and museum tour guide Bachar Al Mohamad Al Chahin, who studied archaeology in Damascus.

Maria Eichhorn, who has been in the news for shutting down London’s Chisenhale Gallery and giving its employees paid leave as her exhibition “5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours,” is also showing in Berlin at Barbara Weiss. Her Film Lexicon of Sexual Practices (1999/2005/2008/2014/2015) documents various sex acts on 16mm film, each lasting approximately 2 minutes and 40 seconds. A projector is installed in an otherwise empty and fully lit gallery, and viewers are prompted by a wall text to choose which sex act they’d like to see. It is refreshingly weird to ask to ask a humorless gallery assistant to see “cunnilingus.” The sex acts are sterilely depicted on a white background: in the aforementioned cunnilingus, there’s no sense of urgency, but rather a polite flicking of the tongue. The lightness of the room refuses the theatrical quality of watching porn on 16mm, and aggressively wrests cinema and pornography’s tendency to invite the viewer to project their fantasies onto the motion picture’s subject.

Lastly, Maria Nordman’s “Street Project” performance at Konrad Fischer was not a performance, as the artist attests, but rather an action, “just a little thing.” When I arrived, the artist was standing on the street explaining some of her past projects and her thoughts relating to time, memory, place, and sculpture, as she was surrounded by a bevy of entirely disarmed art professionals holding the books and items she had used in her presentation. She pressed her hand up to mine and said, “This is the closest I can get without touching you. But there are so many other distances at which we could be away from each other. In this way, this is the largest work on earth, as we could be an entire world apart.” At the end of her “action,” she asked everyone what they wanted to do. “Are you thirsty? Do you want coffee? Let’s take a vote, shall we make a performance at the park across the street or go to the café?” Nordman’s refusal to refer to the work as performance seems apt: it’s rather a refusal of professional pressure, of superficial social drive-bys, of the bizarre exhausting violence of the “gallery dinner.” Nordman’s medium is memory, and as such, she politely requested that I not use the iPhone photos I impulsively took during her performance. She would rather I feel the weight of her first monograph in my hands, and the texture of the raw linen that encases it.

Nordman reminds me that art isn’t just a medium for taxes and capital, but also always an experience or memory, whether embodied by action or object. To me, this is not a regression to the heyday of postmodern immateriality myths, but rather something perennial, or even new: that art, when relieved of expectation, can be emancipatory.