At times, history is anachronistic. Documentary practices define a film genre that existed before the invention of film. In a sense, the documentary impulse was what made film possible in the first place: workers leaving the factory, the rustling of leaves, a train entering the station, or a street scene can all be described as attempts to mobilize an equality of indifference against the hierarchies of representation. As French philosopher Jacques Rancière put it, only when the anonymous became the subject matter of art could the actualités [actuality films]—the act of recording such subject matter—become an art, instead of say a craft or technique. But though temporarily freed from the obligation to erect monuments to authority, the arts of mechanical reproduction emerged with trappings of their own making.

The non-fictional camera came to represent the conviction that unmediated access to reality was not only possible, but imperative—a conviction which peaked with Direct Cinema’s usage of hand-held cameras and synchronized sound (before the 1960s documentary sound was synced in post-production and relied heavily on Foley artists). Direct Cinema however—and one could add, most of the genre—tacitly ignores the conventions of realism, namely the technical synthesis that upholds its claims to observational truth. Inverting the subordination of sound to image, the Berlin Documentary Forum—now in its third edition—turns the notion of documental film predicated on ocular proof on its head in order to look at documentary practices across media, bypassing realism and, at times, the visual altogether.

Paradoxically, this year’s Forum, organized by its founding artistic director Hila Peleg and held at Haus der Kulturen der Welt, is about narrative modes and practices. Predicated on Rancière’s observation that the real must be fictionalized in order to be understood, the festival strategically circumvents the commonplace antinomy between the logic of facts and the logic of fiction. Rather than opposing myriad micro-narratives to grand, historical ones, or suggesting that history is nothing but a bunch of stories, the Forum claims images are not univocal; they are cultural constructs rather than optical phenomena, creating and frustrating expectations by coupling and decoupling speech and affections, power and depiction.

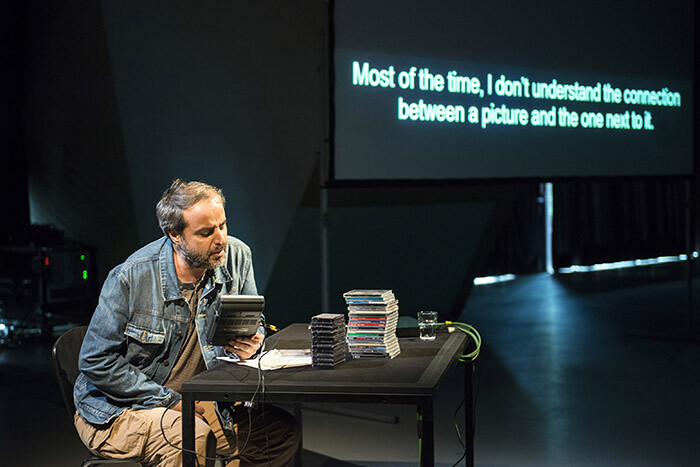

Along with two video installations in situ, the weekend’s events privileged performance and oral presentation, opening with Riding on a Cloud (2014), a touching collaboration between Lebanese artist Rabih Mroué and his brother Yasser, and closing with Roee Rosen’s screening of the fictional works of the ex-Soviet Buried Alive Group and their despondent leader, poet Maxim Komar-Myshkin. Riding on a Cloud’s narrator, Yasser Mroué, is clearly an unreliable one—having been shot by a sniper at seventeen, he was temporarily impaired by aphasia and the inability to recognize images; whilst Rosen conjures myriad fictional characters whose work is discussed by equally fictional commentators. In the experimental films of Parviz Kimiavi, born in Tehran in 1939, real people (re)enact fictionalized versions of their own lives, sketching out surrealist allegories of seclusion and communality. Even in the moments when a semblance of realism remains on view—like in Tōhoku Trilogy (2011–13), a series of filmed interviews by Japanese filmmakers Sakai Ko und Hamaguchi Ryusuke with residents of the area most heavily hit by the 2011 tsunami—the representation of the event emerges from the assembly of disparate voices, at times as cacophony, other times as kinship, yet never autonomous or ontologically stable. Other projects, like the festival’s tour de force “Narco-Capitalism. Mexico on the Brink,” led by cultural theorist Sylvère Lotringer, filmmaker Jesse Lerner, and author Sergio González Rodriguez, foreground interpretation, describing how the import of drugs into the US market fuels the export of weaponry to Mexico in a hellish business cycle that constantly spews out dead bodies, whose widely circulated images obscure rather than elucidate the economic underpinnings and the gendered nature of the violence.

In the installation School (2009–11) by London-based Israeli artist Smadar Dreyfus (on view until July 14, 2014), the recordings of seven different high-school lessons in Tel Aviv are rendered exclusively as Hebrew audio with English subtitling; displayed as a video projection inside of an architectural structure that mimics the structural elements of a school building—classrooms, corridors, and the projection screens suggesting blackboards—the experience is highly immersive, but layered nonetheless. It testifies to the process of socialization and subject formation—clearly a school is an apparatus for the production of citizens—as well as the commotion, turbulence, and confusion of adolescence. As Dreyfus mentions in an interview in the publication accompanying the Forum, it became clear to her upon hearing the recordings that her microphones captured a whole universe of fraught interactions and micro-rebellions that were inaudible to the teachers.

The second installation on display, German filmmaker’s Harun Farocki’s Parallele I-IV [Parallel I-IV] (2012–14), also offers a critique of representation. Taking as its subject matter the computer animations commonly used in videogames, the multichannel work engages in an archaeology of the medium’s visual tropes, from its graphic, and rather humble, beginnings to the current hyperrealist mode. As tempting as it is to trace the genealogy of computer animation back to the invention of perspective in the Renaissance, or to oppose the ubiquity of the subjective camera view with the way it signifies skewed perception in cinema, I couldn’t help thinking that the aesthetics of gaming cannot fully account for its psychology, and that these abstracted environments are more similar to a Skinner box—in the sense of the sequencing of rewards—or to an aquarium—in the sense of a suspended ecology—than to a seventeenth-century Flemish painting.

Parallele I-IV, however, also pointedly addresses the fact that in recent years the visual became wholly mediated; yet the ubiquity of visual technologies introduced a split between image and representation. At present, the global circulation of images goes hand in hand with increasing partitions in the social sphere, segregation, displacement, and inequality. Social media, for example, was hailed as the enabler of the Arab Spring, but the millions who took to the streets achieved no political gains. Could one say that, as artist Hito Steyerl suggests, the gap between the two forms of representation—political on the one hand, cultural on the other—is a constitutive feature of current communication technologies?1 Are the media that enable cultural participation simultaneously generating political exclusion? Current trends in image and visual studies seem wholly inadequate to describe these issues; at the same time, contemporary art lacks the conceptual tools to engage with narrative inflection.

Recognizing the vacuum of tradition it stands upon, the Forum attempted to address these and other issues on a number of experimental registers. Overall the festival was at its best when it indulged in poetic license and flights of fancy, at its worst when it tried to remain on topic. The low point was perhaps “Al Jazeera Replay (Feb 1–4, 2011),” the presentation of Al Jazeera English’s coverage of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. Correspondent Rawya Rageh never broke character, not even when prompted by members of the audience to acknowledge the disingenuousness of the media outlet’s claim to neutrality; clearly, twenty-four hour coverage played a cumulative role in the unfolding of the events. Shuar leader Ampam Karakras, and artists Maria Thereza Alves and Jimmie Durham’s two-part presentation on “Indigenous Activism in the Americas” could have also done with a bit more contextualization; the audience was largely left in the dark about the circumstances surrounding the 1970s compilation of Brazil-based Italian filmmaker Andrea Tonacci’s archive on the Americas. In total, however, this year’s Forum featured an ambitious and thoughtful program, which fully justified the reputation it has already garnered as a cultural reference in Berlin’s often-slight institutional landscape.

Tony Wood, “Reserve Armies of the Imagination,” New Left Review 82 (July–August 2013), https://newleftreview.org/II/82/tony-wood-reserve-armies-of-the-imagination.