In tandem with “Ich kenne kein Weekend: Archive and Collection René Block,” a double-venue exhibition recognizing the work of gallerist, curator, and collector René Block organized in Berlin this autumn, art-agenda presents a three-part feature on Block. Part I and II consist of an interview led by Luca Cerizza, while Part III is an introduction to the current Berlin exhibitions, written by Eva Scharrer. Part I follows, Part II will be published on December 15, and Part III on December 22, 2015.

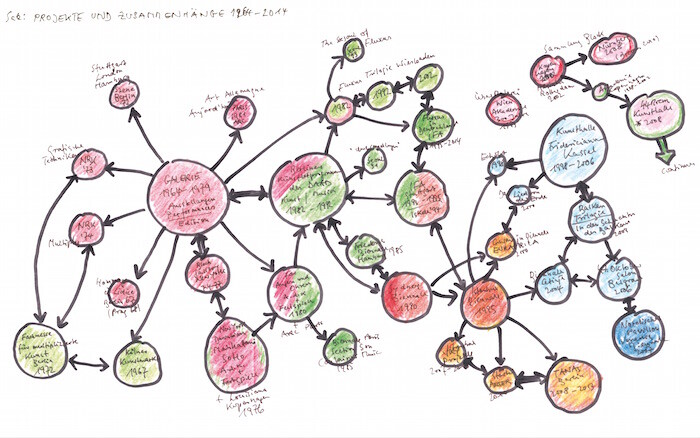

The first time I met René Block with the proposal of writing a profile on his work as a gallerist for art-agenda, he mentioned a forthcoming exhibition and immediately took out a sheet of A4 paper on which he had drawn a colorful map. Composed of a series of circles of different colors connected by arrows, this sketch visualized 50 years of Block’s career, from the opening of Galerie Block in Berlin in 1964 to the planning stages, in 2014, of a double-venue Berlin exhibition on his life’s work. Almost one year later, on September 16, 2015, the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.) and the Berlinische Galerie opened the two-part retrospective “Ich kenne kein Weekend: Archive and Collection René Block,” dedicated to different aspects of his activity, a practice as innovative as it is diverse. Block guided me through the chart, explaining how to read its different colors and connections. A large, pink circle at the center-left represented the work of the Berlin gallery (1964-79). From that point originated a constellation of smaller circles, representing a variety of activities during the 1970s: the New York gallery (1974-77); Block’s involvement with graphics and multiples at n.b.k. (1973-74); and even his role as co-founder of Art Cologne (1967). While reading the chart’s movement forward in time and to the right, almost at its center, I noticed a large circle dominated by a green color, with a small section of pink—on which was written “Berlin artist prog. DAAD Art/Music 1982–1992.” Below this, connected to both the green circle and the initial large, pink one, another circle stated: “Für Augen und Ohren” [For eyes and ears], the title of the key exhibition on the visual and object-oriented character of avant-garde music that Block organized in Berlin and Paris in 1980.

My attention was drawn to the center of the map and, one could say, to the core of Block’s interests: avant-garde music. It was not explicitly written on the area of the map representing Galerie Block but, in fact, experimental music was at the heart of Block’s programming there as well. Considering that “Ich kenne kein Weekend” covers the whole spectrum of Block’s activities—including the directorship of Kunsthalle Fridericianum in Kassel (1997-2006), and the curatorship of biennials in Hamburg (1985), Sydney (1990), and Istanbul (1995) (part of his work towards opening up new possibilities for contemporary art in areas that were previously considered peripheral)—I proposed to focus, in the interview that follows, on the center of the map and its reverberations: Block’s undertakings related to music through the 1960s and ’70s, up until “Für Augen und Ohren.”

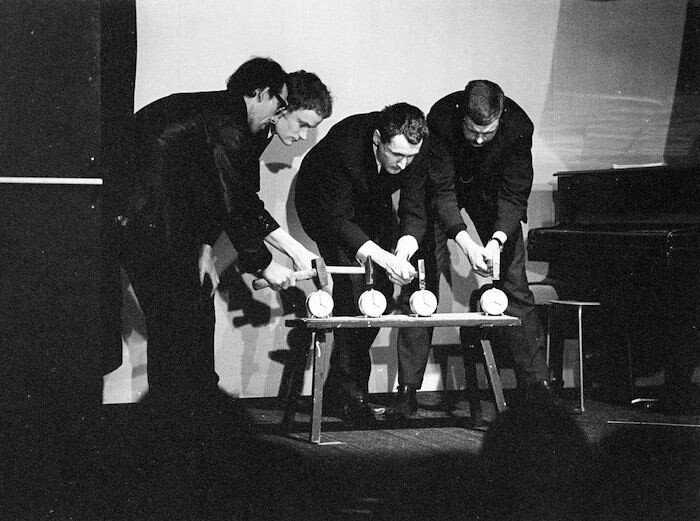

Starting with Galerie Block, and continuing through his position as director of DAAD’s artistic program (1982-9), Block introduced the Berlin cultural scene to a wide spectrum of avant-garde musical expressions which were, especially through the 1960s and ’70s, neglected by its local audience.1 The music championed by Block was marked by an uncompromising opposition to the Western classical music tradition and characterized by elements of performance and installation. While Block “never advocated a truly consistent aesthetic line”2 and his programs featured artists and subjects ranging from John Cage to Tangerine Dream, from La Monte Young to electronic music, from Morton Feldman to Walkmans, it is also true that Fluxus music constituted a crucial part of his activity over the years. If “Fluxus music […] represents no unified musical form or conception, but becomes interesting just because of [its] different, often completely contradictory approaches,”3 certainly music was one of the tools Fluxus used most frequently to attack the fortress of highbrow culture. Many of the artists that were later considered as part of the movement (George Brecht, Al Hansen, Dick Higgins, Robert Filliou) attended the class held by John Cage at the New School for Social Research in New York between 1956 and 1960, and others (like Paik and Beuys) had classical music training.4 Concepts like chance, randomness and non-intention, use of the environment, and a minimalist approach, matured under Cage’s influence, were peppered by a generally humorous attitude and a strong sense of theatricality, and took the stage in different Fluxus festivals in Europe.

Defined by George Maciunas as a “fusion of Spike Jones, Vaudeville, gag, children’s games, and Duchamp,”5 Fluxus performs a violent yet highly sarcastic attack on the conventions of Western classical music—such as its notation and some of its most iconic instruments—whose presentations intentionally puzzle and provoke their audiences. For example, while a performance by Dick Higgins included shooting a rifle at a pre-fabricated music score (1000 Symphonies, 1967), performances by the likes of Nam June Paik, Philip Corner, Joseph Beuys, and George Maciunas used pianos as their material, in a series of physical and symbolic acts against the instrument par excellence of bourgeois musical tradition. In opposition to the transcendent aspirations of highbrow musical culture, Fluxus music celebrated the banality and simplicity of everyday life, resulting in a deadpan humor and advocating the idea of boundless freedom, which was especially relevant in West Berlin during the Cold War. While Fluxus music follows musician and musicologist Alan Licht’s assertion that, historically, “most sound by visual artists isn’t classifiable as sound art—it’s too performance oriented,”6 it is precisely this performative character that makes Fluxus (and other forms of music championed by Block) peculiar in relation to music today.

As is well known, digitalization has radically changed the way we produce, distribute, and listen to music, perhaps exacerbating the state of distraction Walter Benjamin discussed in relation to our experience of it.7 If nowadays music, like visual art, is increasingly accessed through technological mediation, often of low quality, the performing arts (performance art, choreography, storytelling, lecturing, and other time-based expressions) are gaining new interest in contemporary art discourse, perhaps for the uniqueness of a direct, unmediated music and sound live experience. Hence Block’s years of engagement with music, with his emphasis on the performative, physical, and sculptural nature of music and sound, and with the conceptual, absurdist, yet critical, iconoclastic character of his programming, merit being reevaluated in the present day. With this in mind, I asked René Block to recollect and comment on a short selection of images from the several music performances and exhibitions he organized. In doing so I hope to bring back the sense and the value of those moments to the majority of people who never witnessed them—the memory of an experience mediated by an eye and ear witness.

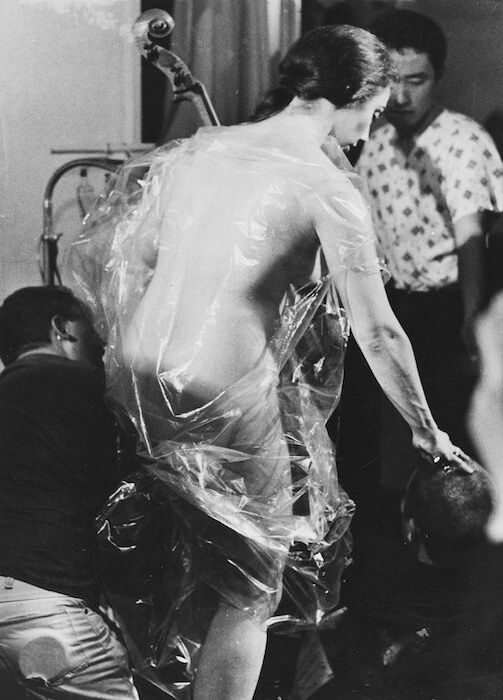

1) Nam June Paik with Charlotte Moorman (May 14–15, 1965, Galerie Block, Berlin)

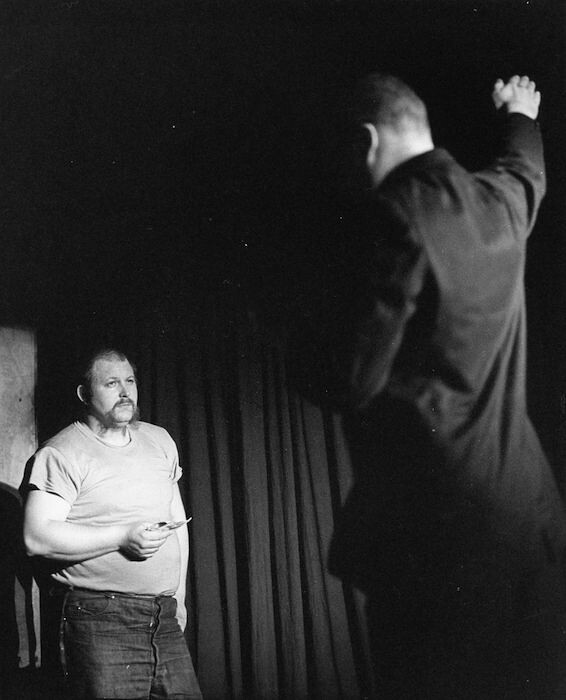

Luca Cerizza: The visual and performative element of much of the music you championed was already evident in the first music performance organized at Galerie Block in Berlin. Like other artists involved with Fluxus, Paik studied music; he wrote a thesis on Arnold Schönberg, and worked in the Electronic Music Studio at Westdeutschen Rundfunk (WDR) in Cologne. After he discovered Cage in Darmstadt, he gave various Cage-inspired piano performances between 1959 and 1963. Paik largely “used” music and sound as part of his performances. In a text on Fluxus, you wrote that Charlotte Moorman brought a sexual element to Paik’s work. How was this element perceptible during the performance? Do you remember the reaction of the audience and, more generally, how your experimental music proposals were received at that time in Berlin?

René Block: It was Paik who brought eroticism and sexuality as a visual element into his music. You could say that he turned Eroica into Erotica. There are these early scores of his that were meant to be played on the piano with an erect penis instead of fingers. His partner and interpreter, Moorman, had to play a number of pieces topless. In 1964, this was still quite scandalous. While this extension of the musical performance was tolerated in Europe, Moorman was arrested in the middle of her performance of Paik’s Opera Sextronique at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in Manhattan in 1967 and charged with indecent exposure. She was jailed for a few weeks.

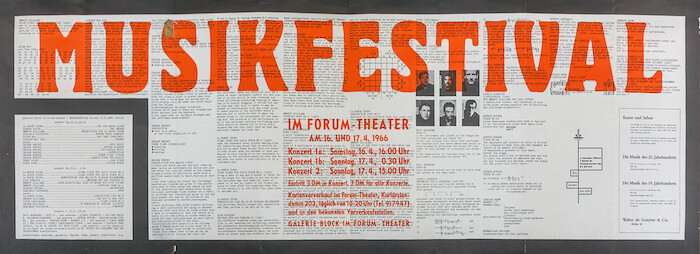

2) “Musikfestival” (April 16–17, 1966, Forum Theater, Berlin)

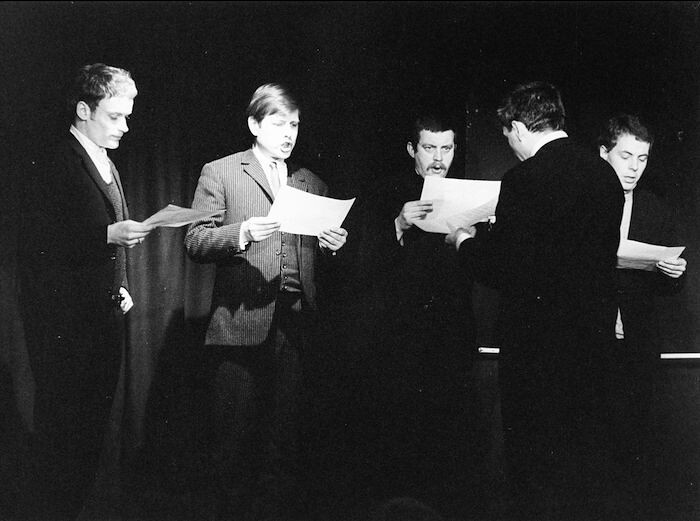

LC: This event consisted of three concerts at the Forum Theater and featured works by George Brecht, Stanley Brouwn, Ludwig Gosewitz, Dick Higgins, La Monte Young, George Maciunas, Jackson Mac Low, Robin Page, Benjamin Patterson, Terry Riley, Dieter Roth (or Diter Rot, as he is credited in the program), Gerhard Rühm, Tomas Schmit, Vangelis Tsakiridis, Emmett Williams. “Musikfestival” was in line with events such as the Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik in Wiesbaden (1962), the first Fluxus presentation in Europe. Yet, in the case of “Musikfestival,” the program included musicians not directly involved with that group, such as minimalists Riley and Young. What was the aim of this festival and how did you manage to use a space outside of your gallery? What kind of possibilities did it allow you?

RB: I didn’t have the opportunity to visit the early Fluxus festivals in Wiesbaden, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, or Düsseldorf. So I tried to bring the artists that had been involved in those events to Berlin for solo performances that we called “Soiréen” (after the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich). Then, with the “Musikfestival,” we wanted to present different aspects of Fluxus music for the first time on a broader scale. We wanted to demonstrate that the works are actually scores which were not meant to be performed by their authors only, but could be played by other interpreters as well. For this, I wanted to leave the gallery and enter the classical theater stage with a space for the audience. Also to demonstrate that Fluxus works were meant to be played in front of an audience, and not, like happenings, with the audience.

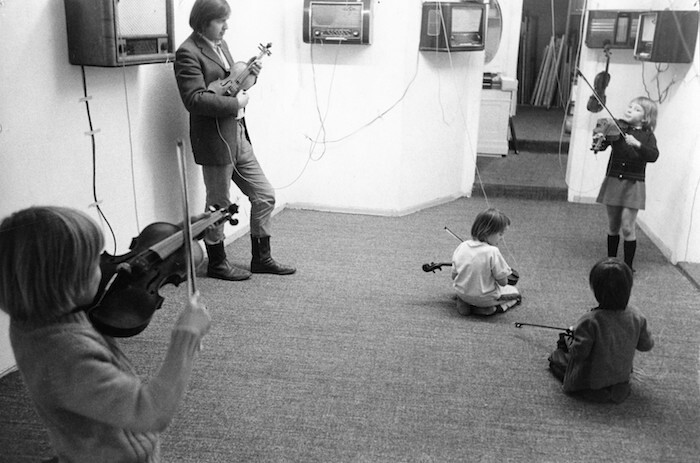

3) Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles, Flux-Konzert (October 4, 1966, Galerie Block, Berlin)

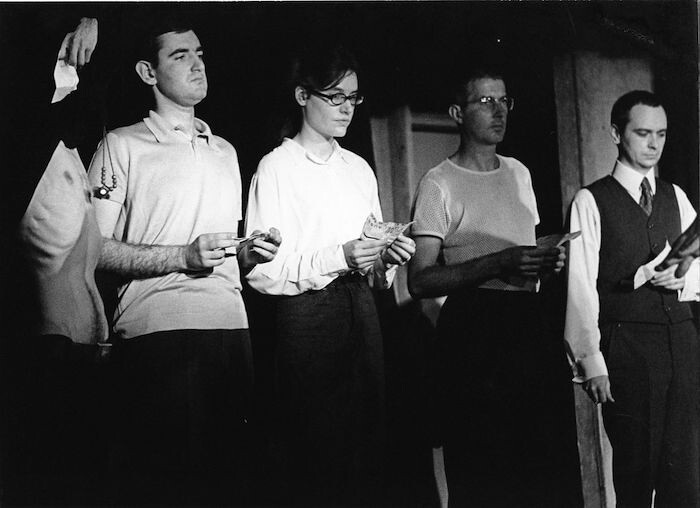

LC: In the photographic documentation of this event, we see various activities, such as performers reading from a strip of paper, Knowles shining her shoes, Higgins pointing a spotlight towards the audience, and the audience blowing into whistles…

RB: In a classical Fluxus concert, sound is created with the simplest of means. The rustling of paper can be very loud, and with different kinds of paper, you create different sounds.

My gratitude and thanks to Eva Scharrer for her generous help in the research phase of this article.

Ursula Block, René Block’s wife, played an important role in connecting the Berlin public to different forms of avant-garde music. For more than 30 years (1981-2014), she ran Gelbe Musik, a record shop devoted to minimal, electronic, world, industrial, and extreme noise music. Located at Schaperstraße 11, in West Berlin, the shop was one of the best of its kind in Europe.

Klaus Ebbeke, “Music at the Block Gallery,” in Mit dem Kopf durch die Wand, Head Through the Wall, Gennem Hovedet Muren, Collection Block,” eds. Elisabeth Delin Hansen and René Block (Copenhagen: Statens Museum for Kunst, 1992), 177.

René Block, “Fluxus Music: an everyday event. A lecture,” in A Long Tale with Many Knots. Fluxus in Germany 1962-1994, eds. René Block and Gabriele Knapstein (Stuttgart: ifa Stuttgart, 1995), 36.

For an account of Cage’s educational influence on the New York art scene, see: Bruce Altshuler, “The Cage Class,” in Heckling Catalogue, ed. Nancy Dwyer (Ghent: Imschoot Uitgevers, 1991), 17-21.

Quoted in Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, Art since 1900 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 458.

Alan Licht, Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories (New York: Rizzoli, 2007), 141.

Namely in his text “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1936).