Brought to you by Kulturprojekte Berlin, the producers of last year’s “based in Berlin” survey, Berlin Art Week is a mayoral initiative funded by the Senate Chancellery for Economics and the Senate Chancellery for Cultural Affairs, which seeks to make up for the loss of the ill-fated Art Forum Berlin by labeling the week around abc (Art Berlin Contemporary) as if some sort of extra cultural activity is actually taking place. Most of the city’s institutions are listed on the Art Week’s website, but for anyone who lives in the city, it feels rather paltry to see announcements featuring shows which opened weeks, even months ago, re-branded to sound brand new. It would seem that pretty much everything else in the city, which is being radically redesigned for the benefit of the leisure classes, is being marketed to the occasional tourist or the potential investor.

But to begin rather with a nuanced comment on the city as a haven for real estate speculation, we recommend seeing how architect Arno Brandlhuber flooded the basement of his own signature building on Brunnenstrasse for the show at KOW, “Im Archipel,” which runs concurrently at n.b.k. (Neuer Berliner Kunstverein), in one of the few de facto institutional partnerships of the Art Week.

If you ask Berliners, on the other hand, they will tell you that the real opening of the season preceded City Hall’s official calendar. The St. Agnes Church—an iconic Brutalist building built in 1967 by Werner Düttmann—was recently acquired by gallerist Johann König (and will undergo a full renovation—by Brandlhuber, no less—before opening next year). In an ad hoc event on August 29, the doors to the chapel were thrown open for artist Michaela Meise, who performed songs—including religious hymns—from her recent album Preis dem Todesüberwinder. And St. Agnes was kept alive throughout Berlin Art Week, functioning under the aegis of the now-defunct artist-run Times Bar as an informal meeting point. Other noteworthy new venues debuting this week were Supportico Lopez’s and Sommer & Kohl’s exhibition spaces. It would seem that the two young galleries have come of age, leaving their more modest original venues to relocate to a new building at Kurfürstenstrasse 13/14, the property of artist Douglas Gordon, in which several artists will also base their studios.

For every distinctive building that gets recovered, however, many others get torn down, and the sale of city landmarks like St. Agnes is symptomatic of a contracting public sphere. Whilst initiatives like the Berlin Art Week seek to ostensibly commodify the city’s cultural scene, the lack of crossover is patent, and though Berlin’s scene remains resilient, its space is increasingly under siege.

But while the music is still playing, check out the haunting images of Carol Rama’s “Spazio Anche Più che Tempo” at Isabella Bortolozzi, and, on a completely different note, the endless torrent of buffoonery in Rodney Graham’s “Canadian Humourist” at Johnen Galerie, or the readymade James Turrell that Mike Nelson excavated for neugerriemschneider in a derelict building on Gartenstrasse 6 for his “Space that Saw (Platform for a Performance in Two Parts)”—which feels like entering the zone of Tarkovsky’s Stalker.

Though not officially part of the Berlin Art Week, the daadgalerie has also just opened the “Agency of Unrealized Projects,” the newest iteration of the project by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Julia Peyton-Jones, Julieta Aranda, and Anton Vidokle which seeks to chart the territory of unrealized artworks. Speaking at the ancillary symposium held last Sunday, Jimmie Durham told the audience about one of his manifold unrealized projects, a series of equine statues the artist sought to install in various world capitals. Realizing that no city would be willing to fund a riderless horse, the artist conceded that he could add some famous people: say, Einstein, he suggested, on horseback for any given square in Berlin.

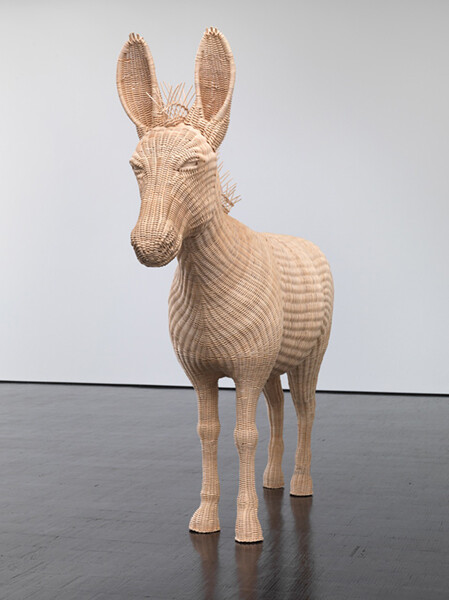

Einstein notwithstanding, there is an unstated gender dimension in equestrian symbology, which dovetails with the thrust to rebuild Kaiser Wilhelm’s palace on the site of the former East German Palast der Republik in Berlin-Mitte. In heroic societies, the public space is thoroughly defined by the male. Whereas horses are everywhere, women and workers are rendered invisible. If instead of stallions you are fond of donkeys—the animal with whom, by no accident, the latter are associated—you will have to visit Mai-Thu Perret’s “Beasts of Burden” at Galerie Barbara Weiss.

Besides Balthazar (2012), a rattan ass whose name evokes the eponymous film by Robert Bresson, Au Hazard Balthazar (1966)—in which the humiliation and sufferance of the animal is paralleled with that of the young woman who named him—“Beasts of Burden” comprises a wide array of works, revolving around the blind spots of the modern.

Throughout western history, the ontology of art has never been settled. As a consequence, art has been divided into two: the manifold crafts one calls fine arts, on the one hand, and the latent promise of a unified universal, on the other. Hegel’s “end of art” is not the end of art as such, but the end of one of its aspects: art as the pedestrian activity of the artisan or the craftsman. Whereas modernism challenged the divide between industrial objects and artworks, it stopped short of erasing the age-old distinction between those who toil in manual labor and those who pursue artistic endeavors. In every artwork one can thus still find this fundamental, unresolved tension between art and work.

The series of pieces of twisted cloth glazed onto ceramic tiles that form the focus of Perret’s show sits squarely at the crux of the matter. Revolving around the silent travails of chambermaids, janitresses, or cleaning women, Beasts of Burden (2012) stands midway between the suggestion of the lines of force imprinted by the laborer’s hand and the uncanny allure of mummified drapery. But these objects—like Nikki I (2012), a variation on the recurring trope of the mannequin and an avatar for the artist qua voodoo doll—can be also seen as part of a wider narrative. In her open-ended project The Crystal Frontier (1999–present), Perret began chronicling the lives of the women in a fictional New Mexico hippie commune, whose tokens of self-expression are neither utilitarian nor decorative, and remain an inconvenient reminder of modernism’s failure to mend the strained relation between artistic autonomy and social emancipation. Crisscrossing references from what came to be known as the lingua franca of modernism with Indian Tantric Painting or folkloric traditions, Perret’s objects maintain a troublesome double nature as both craft and claim, a testimony to the lasting tension between subject matter and formal expression, and to how art is and has always been a Janus-faced activity comprising contradictory motives.

Against the background of the Berlin Art Week, Beasts of Burden can also be seen as an effort to render visible the sort of plights that are usually confined to domestic quarters and barred from the public sphere. Despite not having much else in common, the concerns of both Perret and Brandlhuber—for whom Berlin’s inner city appears as an island of wealth amidst a ring of exclusion—stand at the vanishing point of a common horizon of shared social utopias and political ideals. The future might belong to the urban loft, but while the last launderette still stands, a life not yet stripped down to the core of its economic function can perhaps still be lived.