Hamburger Bahnhof—Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart, Berlin

September 9–November 14, 2015

On the occasion of their nomination for the Preis der Nationalgalerie in 2015, Slavs and Tatars’ work can presently be viewed at two locations in Berlin. One is the Hamburger Bahnhof, the institution hosting the prize. There, books by the art collective are offered up for viewing in what looks like a swingers’ club for bookworms. By now, Slavs and Tatars have published ten books, making these the heart of their production. The other exhibition is at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler. Although the gallery show lacks the legs that lure and the dangling swings of the Hamburger Bahnhof presentation, it is far more daring. Together, the two sites unlock the universe of holistic heuristics Slavs and Tatars have been constructing for almost a decade. In this universe, the veils of obscurity that fell over the Eurasian territory, covering it in a neoliberal economy of uniform individualism, are lifted.

Slavs and Tatars are supreme wordsmiths. Hardly another letter in the pool of Slavic languages of Eurasia requires so much artistry in articulation or, for that matter, causes so much transcription trouble in the West as the Dž or Dż [d͡z] in the exhibition’s title. But “Dschinn and Dschuice” does not simply poke fun at the mishaps caused by the German pronunciation of digraphs, like it easily could. Instead, Slavs and Tatars deploy the digraph where it itches the most: inside habits of copious consumption and other capitalist crusades. In synch with the works, this digraph echoes the crossbreed of colonial enterprises, media mercantilism, and policies of tear-gassing the foreign, the disobedient, or simply the cacophonous elements that Slavs and Tatars’ interests tend to turn to. “Dschinn and Dschuice” alludes to the perverse pleasure that the unlearning of culture has produced within the German media landscape.

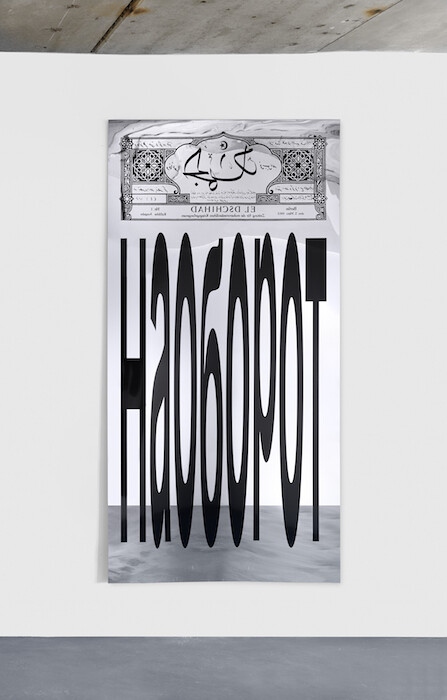

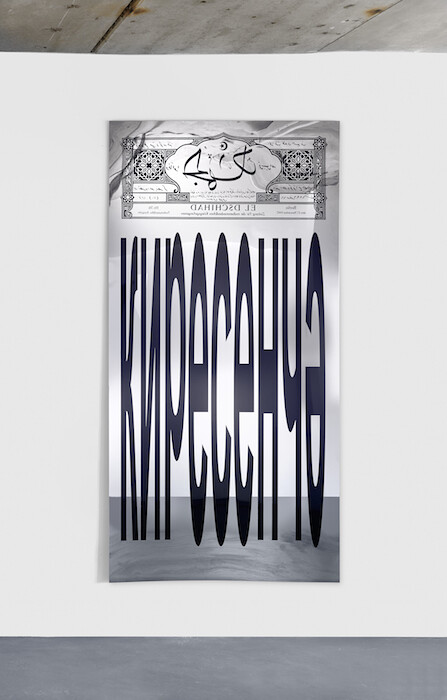

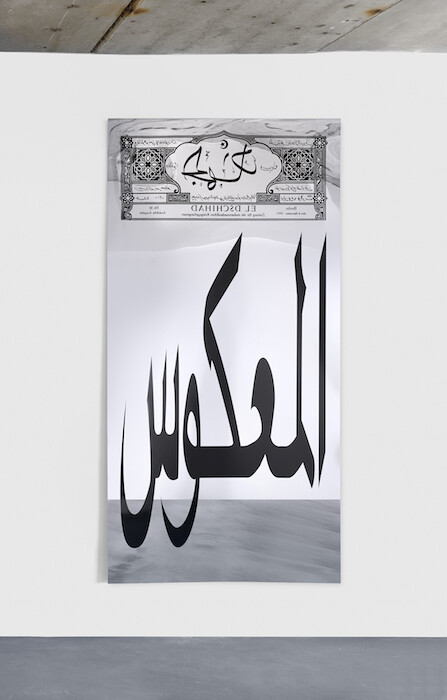

The historical reference point for Reverse Dschihad-Urdu and Reverse Dschihad-Russian (both 2015) is the newspaper El Dschihad, which was published under the auspices of Kaiser Wilhelm II and primarily aimed at Muslim prisoners of war held at a camp outside of Berlin. The Muslim prisoners would be sent back to the front reprogrammed, spreading an anti-imperial message, but fighting for the Germans. In parallel, the exhibition’s accompanying text points to the British reality TV show I’m a Celebrity…Get Me Out of Here! (referred to in Germany as “Dschungelcamp,” [Jungle Camp]), another striking example of Germanized nonsense phonetics. Needless to say, the other jungle—the jungle of Calais—along with the perversity of its humiliating denomination is just an association away. Both the perverse pleasure of unlearning and the perversity of humiliating denominations are significant carriers of the repressive power language bears within the policed borders of Europe today, keeping its uniform individualism unblemished.

Yet, just as it is more than “half gin and half Rose’s lime juice and nothing else” that makes a “real” gimlet, there are more ambivalent elements at play in “Dschinn and Dschuice.” The favored cocktail of Raymond Chandler’s surrogate Terry Lennox from the 1953 novel The Long Goodbye goes further back than a history of dapper drinking in gentlemen’s clubs and its conversations circling around command-and-conquer tactics and erogenous zones. It did tend to get dirty. Gimlet was the scurvy and slackness prophylactic on board the ships of the British Empire taking to the South Seas at the end of the nineteenth century. Similarly, the most emblematic work of “Dschinn and Dschuice,”—Reverse Joy (Kha) (2012)—is an ambiguous fountain of joy. The fluid flowing out of its pump is carmine red. It is the carmine red of lips ready to sweet talk and of tongues able to roll (a recessive phenotype mostly found in the Slavic population of the Balkans). The pigment is fittingly produced out of Armenian and Polish cochineal. Slavs and Tatars’ works ceaselessly point to details such as these. Factually, Reverse Joy (Kha) (2012) commemorates the celebration and parallel mourning of the death of Hussein ibn Ali, grandson of the prophet Muhammed. Yet, the fluid splatters all over glazed white tiles, the material ground of detention cells that keep despots in power worldwide.

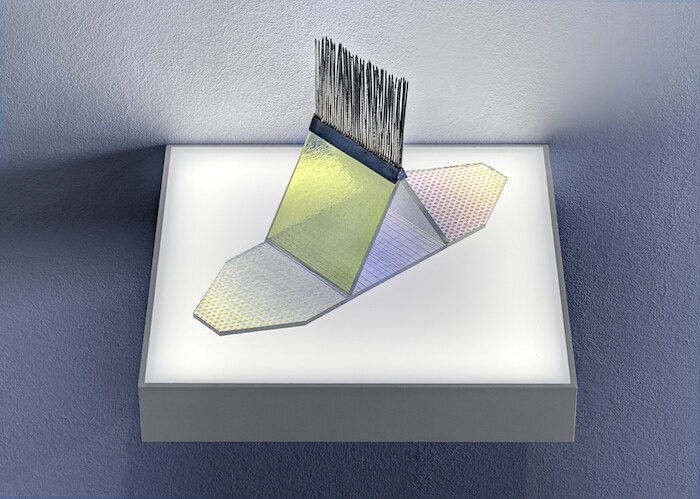

Once, when asked in an interview what is the one piece of art that they could not live without, Slavs and Tatars replied: a rahlé.1 A rahlé is typically a handmade wooden stand for a Qur’an script. The intricacy of its manufacture, the meditative nature of its religious usage, its simple beauty reverberates in Zulf (brunette) (2014), a sculpture in the form of a rahlé with human hair falling down its sides. Two other works, comb-like glass objects—Irokez (2014) and Bazm u Razm (Joint 3) (2015)—could function as grooming agents for its luscious mane. Together they imply the cruelest rule of cultural assimilation today: if you are well-spoken, groomed, and for that reason perceived as not outlandish, you are in. Again and again the razzle-dazzle of Slavs and Tatars’ research releases such undisciplined interdisciplinary creatures upon us. In search of kindred spirits we realize that this just might be the “Gay Science” Friedrich Nietzsche meant when writing: “Sharp and mild, dull and keen, well known and strange, dirty and clean, where both the fool and wise are seen: All this am I, have ever been,—in me a dove, snake and swine convene.”2

“Questionnaire: Slavs and Tatars,” frieze no 174 (May 2012): 248.

Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Proverb Speaks,” Prelude to The Gay Science. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 13.