An autumnal smiley face—made out of two bicycle wheels, some tree twigs, and some dry leaves (freckles from summer?)—is the first thing greeting the viewer of Blake Rayne’s “Shade Subscription.” Once we go behind the wall abutting this work, named after the artist himself, Blake (2011), it seems only appropriate that we should now come upon the hapless bicycle frame, turned upside down: a true downer, a bike going nowhere.

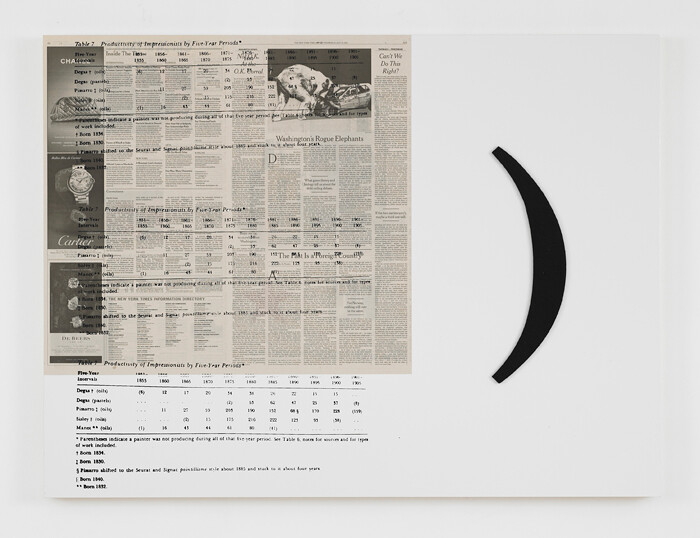

The logic of the readymade dictates as much, as Rayne illustrates with his series of paintings Rest in Shade (2011). There are literally endless issues of the New York Times that could have been used here, a new one being produced every day. But Rayne has chosen to show us only the reverse side of the front page, which has its daily constants: Chanel, for instance, has a monopoly on the upper-left-hand corner of page two. But by superimposing these newspaper pages with a scholarly graph showing us the number of paintings produced each decade by some famous Impressionists, Rayne wants to suggest that the same logic—endless production across a spectrum of variations—was at play in their work. On this point the current show adds an intriguing suggestion. Perhaps there is more in common between the readymade and abstraction than one might surmise at first: they are both interested in the relatively formless space of possibility: the space before reality takes an individualized shape.

The main work in this show, Slöt (2011), could be described as a machine for artistic production. Wedged tightly between two gallery walls, Rayne has aligned thirteen canvases in such a way that only the two outside works can be seen from the ground floor, and one of these outside canvases is wrapped in plastic packaging. From the mezzanine above, the impression is of a gigantic canvas container. The small visible portion of the fifth canvas shows us what looks like an organic shape, part of a plant or bird. Indeed, two of the partially hidden works refer to old themes of the artist, even if the visitor would not necessarily know this. What do they matter, these old ideas? They are now in the past, replaced by the next big thing. While dramatizing the slightly embarrassing concept of an artistic career, this piece is also a reflection on the fall from grace which is an essential part of every artwork. What started as limitless possibility becomes one work among millions, and from this surrender to the world it can never recover. It is not a mechanical process, of course, as Rayne tries to show by including and thus depicting a number of accidents along the way.

Blake Rayne grapples here with important questions, thoughtful questions. He is still, as in previous shows in New York and Bergen, deeply concerned with the status of painting in the age of mechanical reproduction, but he seems to have reconceived what the main challenge to painting really is. Rather than reducing painting to its material medium, Rayne has reduced it to its immaterial beginnings: his work makes explicit and visible the moment when a painting could have become anything. By moving in this direction, Rayne is forced to move further away from painting than he was ever willing to before. He has not abandoned it: his installations are still largely composed around the theme of painting itself. And perhaps possibility is not formless after all—or the artist would not have succeeded in including so many alternatives within a single work, like a garden of forking paths.