Berlin’s history of internecine violence is visible on its civic surface, a characteristic that holds currency in both mainstream and art tourism; what differentiates these two modes is a style rather than a politics. Who can say what a city means?

Gentrification mistakes lack of capital for lack of life, confuses the unexploited with the uninhabited. Over the course of its 18 years, the history of the Berlin Biennale has paralleled the drastic conversion of its symbolic center—the KW Institute for Contemporary Art and surrounding area on Auguststrasse—from post-GDR bohemia to a neoliberalism fully realized. For this year’s edition of the biennial, the ninth, curators Lauren Boyle, Solomon Chase, Marco Roso, and David Toro (known collectively as DIS) propose to orient audiences differently, moving the exhibition’s main venue to the Akademie der Künste on Pariser Platz, adjacent to the Brandenburg Gate, an area populated mostly by tourists, government officials employed in nearby offices, and police.

The appointment of DIS, best known as the publisher of the eponymous online magazine, exacerbated existing polarities among local artists and producers, where distrust of all that’s mediagenic, internet-literate, or American often barely disguises casual classism, or a nostalgia for the difference the city (and its art scene) once represented. I’m less compelled by DIS’s style than I am by its ability to untether retrograde art-world value judgments from their favored objects—presenting work that can at least identify, if not undo, received ideas around aesthetics, discourse, and power—though that’s not as present in this exhibition as it has been in DIS Magazine; perhaps that critique inevitably becomes less powerful or less attractive as its bearers grow more proximate to the institutional art world.

The biennial’s look is predictable, in a way, as though the curators have scaled up and spatialized the contents of their website: there’s a wealth of HD video, fashion photography, pictures of young people. The atrium of the Akademie der Künste is populated with flat images, many of which are uniform large-scale lightboxes resembling advertising billboards, which constitute a curatorial selection titled “LIT.” Of these, Bjarne Melgaard’s SUPREM(E) (2016) is an apparent collaboration with left-theory publishing house Semiotext(e) and fuckboy streetwear brand Supreme. The top left corner bears the signature white sans serif of the publisher’s Intervention series; a photograph shows a puffy jacket in Supreme’s branded cherry red embroidered with the title of Chris Kraus’s 1997 novel I Love Dick.

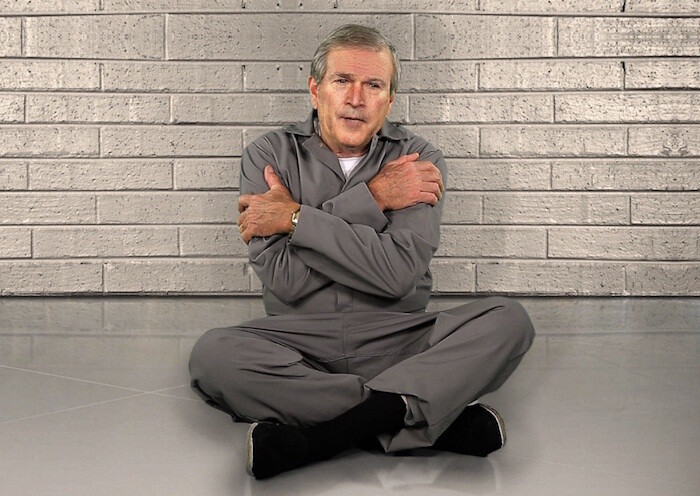

The curators have called on a familiar network of their regular interlocutors to perform familiar tasks, lending formal and conceptual continuity to the exhibition. Also at AdK, Lizzie Fitch and Ryan Trecartin have two videos characteristically featuring groups of young people with modulated voices, Mark Trade and Permission Streak (both 2016), set into custom arenas of the artists’ design. At the European School of Management and Technology, Simon Denny’s large-scale installation Blockchain Visionaries (2016) appropriates the visual vocabulary of the trade fair, proposing three stamp designs (created in collaboration with Berlin-based artist Linda Kantchev), each representing distinct potential directions for the decentralized transaction database technology. At KW, Josh Kline’s video installation Crying Games (2015) uses face substitution software to have actors deliver apologies in character as the warmongers of the 2000s; George Bush, Tony Blair, and Dick Cheney repeat “I’m sorry,” while Condoleezza Rice tells us “some things you just can’t fix.” Though these gestures are all more or less interesting depending on how many times one has seen them before, they effectively crystallize the biennial’s tastes and preoccupations, and work to canonize the curators’ long-standing support of certain post-internet art practices.

Back at AdK, Dress Rehearsal (2016), organized by the Melbourne-based Centre for Style, a fashion curatorial platform run by Matthew Linde, is a happy respite from the biennial’s pervasive shine, and a compelling articulation of what fashion exhibition might look like outside both the parameters of commerce and the high-definition gloss of the post-internet. Roughly conceptualized as a display of post-runway detritus, the installation comprises pieces of clothing, deconstructed chairs, cabinets, and sculpture gathered from various designers, artists, and scrappy Melbourne weirdos. At one end, Susan Cianciolo’s untitled performance (2016) features a woman lying prone, her body mirrored by a life-size doll at her side. Anna-Sophie Berger’s mud coat 1 and 2 and But is that relevant (all 2016), three women’s jackets caked in mud, lie on the floor, a simple and cogent exercise that signals fashion’s meaning-making in the world and apart from the body.

At KW, Amalia Ulman’s installation PRIVILEGE (2016) excerpts the artist’s Instagram feed, presenting short videos across three square screens; next to these is a dance pole and an animatronic taxidermied pigeon named Bob. The videos show Ulman in her Los Angeles office, riding elevators, nursing a pregnant belly, holding Bob while mouthing the words to Fetty Wap’s “Trap Queen.” Further down the same hall, five performers in motion capture suits execute Alexandra Pirici’s Signals (2016) in a darkened room, in which they form both still and moving tableaux of newsfeed content headlines determined through an online algorithm. I watched the group arrange itself into the image of “Woman Protesting Neonazi March in Sweden,” one woman sing an unabridged version of Beyoncé’s “Drunk in Love,” and a group performance of Janelle Monáe’s “Hell You Talmbout.” Live performance of newsfeed content often feels moralistic, like users should be brought to task for absent-mindedly allowing corporations to reorganize the social, but I found something about Pirici’s performing these songs in their entirety convincing, like a deliberate misreading of her own premise, given that social media algorithms are designed for cursory engagement.

Similarly misleading is one of the few pieces not commissioned specifically for the biennial (and made by one of the few artists outside its relatively tight generational frame), Adrian Piper’s Howdy #6 [Second Series] (2015), an image of a prohibitory traffic sign that says “Howdy” projected onto a locked door at the end of two dark hallways at both KW and AdK. Upstairs at AdK, Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff’s installation Untitled (Interiors) (2016) is mounted in what normally functions as a reception room for the academy. Its panoramic windows look out onto a Starbucks from above which snipers regularly survey foreign members of government and their surrounding publics.(1) The same room was used as a fictional American embassy in last year’s season of the television series Homeland, set in Berlin, in which a CIA officer (Claire Danes) restores moral order by killing men of color; the real American embassy is around the corner. Henkel and Pitegoff’s neatly framed photographs of domestic interiors are mounted on walls of mirrored tiles, which reflect and disperse the blush of adjacent orangey lights. The images were taken at the official private residence of the American ambassador, and show potted orchids, French windows, and table dressings at dusk, among other decorative apparatuses of power.

The biennial’s title is “The Present in Drag,” which I at first took to be its curatorial imperative: to overperform aspects of the contemporary in order to produce a kind of queer or camp rendering of that which is misunderstood as politically neutral. Henkel and Pitegoff’s photographs, however, document an already outsized relationship between decorum and violence distinct from any curatorial or artistic exaggeration, seemingly working against the desire to stage the present as spectacle. As a whole, the biennial articulates the sense that disengaging from networks of capital and power is neither effective nor interesting nor possible, instead performing its own complicity.