“Return to Noreturn” revisits Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s 2008 exhibition in the Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern. The anterior references and influences that are often implicated in her works are therefore doubled here, incorporating not only the original exhibition, but also the triggers—personal, literary, historical, cultural—that informed it. Add to this the fact that the Turbine Hall exhibition imagined a scenario projected 50 years into the future—its title was “TH 2058”—but that we are now invited to look back at it from the vantage point of 2012, and the complexity has been shifted up a gear: chronology seems to fold in on itself. With a characteristically light-fingered touch, Gonzalez-Foerster indicates this complexity without laboring it. And indeed for those viewers who, like me, had not seen the original exhibition, it has come to exist instead as a kind of dream-like shared memory.

The solipsistic title alone immediately establishes a framework of references for the exhibition, but rather than fixing intransient points, they work through concentrated evocation. A series of considered measures, or perhaps rather “moments” (a word the artist is fond of using), set the atmosphere. On entering the gallery, we are at once separated from the outside by passing through a heavy-duty plastic curtain, like the ones in industrial cold storage, except that here the PVC strips are red and green like the colored lenses of 3D glasses. A structural pillar off-center in the space, usually ignored, is now made prominent through a coating of brilliant red paint. Meanwhile a steady, dripping sound, like rain drops following a storm, can be heard. Through gentle suggestion, the coordinates of an alternative location are proposed. This becomes most apparent when one reads the text on a wall that begins “I dream we are lying down” and goes on to describe a dream-like dormitory situation, which overlaps with a recollection of long-distance air travel. Words are used to create a state of mind, like mental 3D glasses through which one thinks things differently.

Here, too, are metal bunk beds painted blue and yellow with books lying on them. They’re the most obvious links to “TH 2058,” which envisaged the Turbine Hall as a post-catastrophe shelter, a futuristic dormitory for an unknown state of emergency, or the storage space of a monstrous museum for spookily enlarged versions of 20th century sculptural masterpieces including Calder (the same color red as the painted pillar here); a Bourgeois spider; and an animal skeleton by Cattelan. In the Schipper gallery beyond the bunks is a video on a flatscreen, Romilly (2012), which follows a young girl in school uniform larking amongst the bunk beds in the Turbine Hall with a group of friends. We focus on her captivating face, her red hair and rosebud mouth, as she chats with her friends, looks at her hand-held screen, reclines, and sleeps on the bunks. Slow-paced subtitles meanwhile reflect on the role of children in films: what happened to Dorothy when she returned home from Oz? The boundary between reality and fiction, between real time and film time, is hard to determine, just as the present is infiltrated by memories from the past or projections of the future.

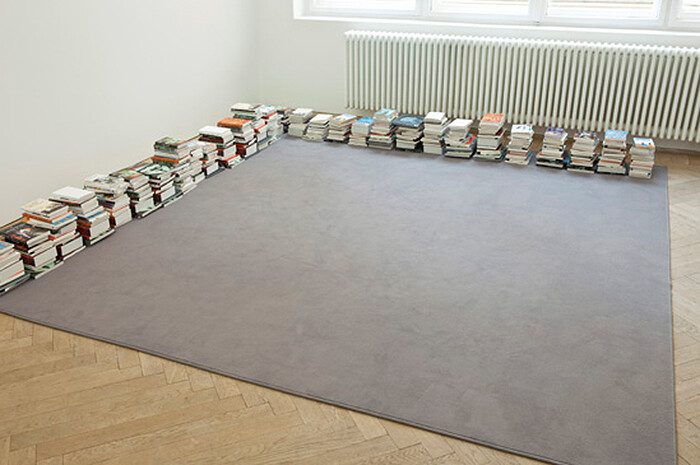

Back through the main room and over a large square grey carpet, framed on two sides by piles of books—Borges, Ballard, Perec, Duras, Le Guin, etc.—and into the final room, we find a large-scale projection of Noreturn (2009), the film Gonzalez-Foerster made at the end of her Turbine Hall exhibition, transforming it into a filmset for a fiction within a fiction. Here again is the rosebud mouthed girl with her school-uniformed friends, playing amongst the giant sculptures, talking, relaxing, daydreaming, to a soundtrack of Arto Lindsay’s wonderfully clashing, ripping, guitar fuzz. Finally they drift off to sleep together on the bunks. The beds, the books, the red leg of the Calder Sculpture, the PVC curtain, the uniformed kids, the girl’s face are all already familiar to us: we have encountered them in the previous rooms. And the subtitles of the film are the very same words we encountered on the wall in the main gallery.

A staged sense of déjà vu occurs, as if these references have been seeded in the viewer’s mind to grow into surrogate memories, indeed, replicants of Gonzalez-Foerster’s own. Regardless of whether we have seen the Turbine Hall show or not, we remember it now, somehow. Having taken in these carefully placed quotations—sonic, visual, textual—when we look at the final film, we see the red-headed girl and think of Dorothy and the cinema; we see the beds and books and think of dreams or air travel; and the monstrous sculptures now conjure an apocalyptic form of shelter, perhaps from the steadily dripping rain. In an exhibition largely about time—cinema time, dream time, traveling time—poised between the past (memory) and the future (imagination), the present exists as an encounter with sound, color, form, text: a moment that becomes a meeting. But perhaps the most poignant encounter takes place with a book on the carpet in one of her “Tapis de Lectures” (2058, 2012). It could be seen as the key work here, and is itself a recurring signature form for Gonzalez-Foerster: a deceptively simple rendering of reference, which joins together literature with space, sculpture, and performance. As the artist says in the catalogue from “TH 2058”: “With time I realized that my obsession with literature and maybe my place in literature is to transfer some aspect of literature into space; there is a possibility of a literature that is beyond print and paper, and probably this is where I hope to be.”