Pasiphae, the protagonist of Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s film series “The Minotaur Trilogy” (2013–15), was the queen of Crete, married to king Minos, the son of Zeus and Europa. Her story is a tale of offence and punishment, but not a straightforward one. Minos, who had just ascended to the throne, asked the god Poseidon for support. Poseidon sent him a white bull, which in Minoan mythology was no bull but the god himself in his pre-Olympian form. The bull was supposed to be sacrificed to Poseidon but Minos deviated from due observance and kept it instead. As a punishment, the god cursed the queen with the most unnatural lust: a sexual urge to mate with the nonhuman other, which was god and animal at once. In order to copulate with the bull, Pasiphae made Daedalus build her a casket in the form of a cow, with which she could arouse the bull’s libido. Mistaking it for a mate, the bull coupled with the man/machine contraption, impregnating the queen inside. Unfortunately for all involved, the materialization of Pasiphae’s monstrous desire was bound to be a monster: the Minotaur.

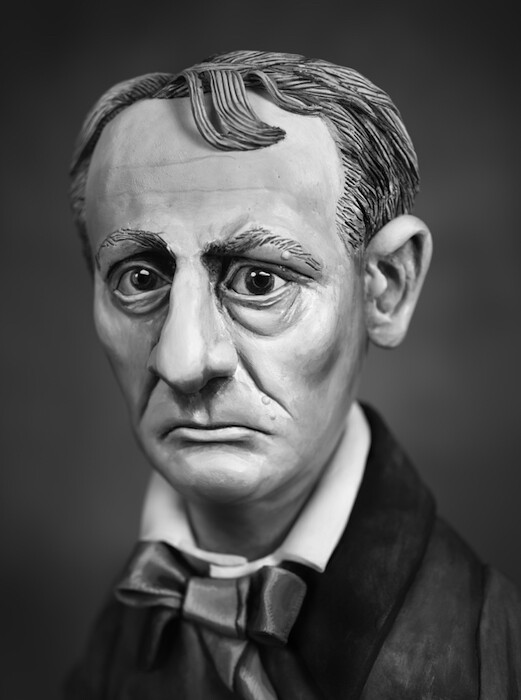

Mary Reid Kelley’s queen was inspired by, and partially adapted from “Pasiphae,” a poem penned by the poet and playwright Algernon Charles Swinburne, himself no stranger to paraphilia. Published only after Swinburne’s death in 1909, due to its licentious nature, “Pasiphae” was styled as a dialogue between the queen and her engineer, Daedalus. The two characters are contrasting, yet symmetrical. Both deviate from nature, albeit in different ways: Pasiphae by bearing a human-animal hybrid, Daedalus by enhancing his anatomy artificially, with the aid of techne. Together they represent the Victorian obsession with mankind’s ability to generate a progeny radically dissimilar from its progenitors, either god-like or beast-like. For the Decadent movement Swinburne was affiliated with, as for the Symbolists and Pre-Raphaelites (the so-called anti-modern movements), the transmogrified or theriomorphic form became a cipher for devolution. Half-man, half-bull, the Minotaur found a second life in nineteenth-century painting and poetry.

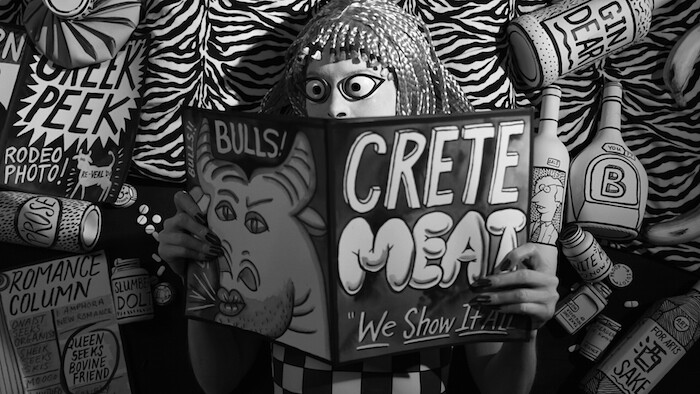

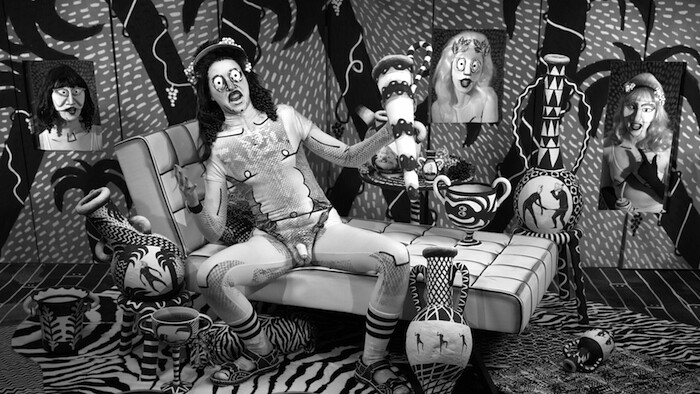

In “The Minotaur Trilogy,” Swinburne’s Pasiphae wears a checkered leotard and Daedalus, dungarees; all characters have cartoonish ball-like eyes, whose deranged gaze seems to pop out of their faces. The queen sports blond Bo Derek-style cornrows, painted cleavage, armpit hair, and bad teeth. Daedalus’ workshop looks like a garden shed; while he saws and hammers, she lies restlessly popping pills and flipping through bovine porn, her ample pubes sprouting out of her bikini line. At Arratia Beer, the space of the gallery is turned into a black box, but for the back room in which a series of ancillary photographs is on display. The trilogy is composed of three separate videos, shown in sequence: Priapus Agonistes (2013), Swinburne’s Pasiphae (2014), and The Thong of Dionysus (2015) with Mary Reid Kelley playing all characters. Reminiscent of German Expressionism, the monochromatic film sets are painted on canvas, in a syncretic blend of camp and queer. The attention to detail is staggering, and all the props have a psychology—they are, in a way, characters, animated by scorn and hysteria. The Minotaur’s father appears as the Osborne Bull, Goddess Venus is a bitch (literally), and the discarded Ariadne, finding “no raisins to live,” attempts suicide with a rubber knife.

The Minotaur preexists her own conception (for this Minotaur is female): she is already there, wandering in the corridors of her graffitied labyrinth, before she even came into being. Because there is no natural food source for an unnatural creature, the Minotaur eats people. Every year the members of the volleyball teams who lose the Baptist church tournaments are sacrificed to the beast. But the Minotaur is not a fiendish creature; she is a confused conflation of god worshipped in animal form, animal mask, real animal, and consecrated animal destined for sacrifice. Rejected by her kin, she lives companionless amidst the bones of her victims. Unlike frat-boy Theseus she is unable to “believe [her] little brain voices” who whisper, “I am in charge of my life; I am the sum of my choices.” For the Minotaur, sanctioned self-improvement is meaningless: her destiny is her morphology. Tired of roaming around her barren dwelling, she ends up crawling into a fetal position and cries herself to death. When Theseus finally finds the beast he is meant to kill, he is overtaken with lust for her listless corpse, curling up besides her. It is fitting that a series that opens with one perversion (zoophilia) would close with another (necrophilia), which also hinges upon the desire for a partner who neither retorts nor rejects. But “The Minotaur Trilogy” is not simply a tale about sexual deviancy and aberrant behavior, it is also an inquiry into what qualifies as deviance—artistically, as well as sexually. The return of the Minotaur is in this sense the return of the repressed, the return of a psyche which is not volitional and whose appetites cannot be disciplined; the return of the transmogrified form, commonly assimilated to the aliens and mutants produced by mass culture and thus marked as “degraded,” or, perhaps most importantly, the return of that which hardly ever finds cultural expression: female sexual desire, so often displaced and misrepresented as the desire to be looked at.