- #150 December 2024

- #149 November 2024

- #148 October 2024

- #147 September 2024

- #146 June 2024

- #145 May 2024

- #144 April 2024

- #143 March 2024

- #142 February 2024

- #141 December 2023

- #140 November 2023

- #139 October 2023

- #138 September 2023

- #137 June 2023

- #136 May 2023

- #135 April 2023

- #134 March 2023

- #133 February 2023

- #132 December 2022

- #131 November 2022

- #130 October 2022

- #129 September 2022

- #128 June 2022

- #127 May 2022

- #126 April 2022

- #125 March 2022

- #124 February 2022

- #123 December 2021

- #122 November 2021

- #121 October 2021

- #120 September 2021

- #119 June 2021

- #118 May 2021

- #117 April 2021

- #116 March 2021

- #115 February 2021

- #114 December 2020

- #113 November 2020

- #112 October 2020

- #111 September 2020

- #110 June 2020

- #109 May 2020

- #108 April 2020

- #107 March 2020

- #106 February 2020

- #105 December 2019

- #104 November 2019

- #103 October 2019

- #102 September 2019

- #101 June 2019

- #100 May 2019

- #99 April 2019

- #98 March 2019

- #97 February 2019

- #96 January 2019

- #95 November 2018

- #94 October 2018

- #93 September 2018

- #92 June 2018

- #91 May 2018

- #90 April 2018

- #89 March 2018

- #88 February 2018

- #87 December 2017

- #86 November 2017

- #85 October 2017

- #84 September 2017

- #83 June 2017

- #82 May 2017

- #81 April 2017

- #80 March 2017

- #79 February 2017

- #78 December 2016

- #77 November 2016

- #76 October 2016

- #75 September 2016

- #74 June 2016

- #73 May 2016

- #72 April 2016

- #71 March 2016

- #70 February 2016

- #69 January 2016

- #68 December 2015

- #67 November 2015

- #66 October 2015

- #65 May 2015

- #64 April 2015

- #63 March 2015

- #62 February 2015

- #61 January 2015

- #60 December 2014

- #59 November 2014

- #58 October 2014

- #57 September 2014

- #56 June 2014

- #55 May 2014

- #54 April 2014

- #53 March 2014

- #52 February 2014

- #51 January 2014

- #50 December 2013

- #49 November 2013

- #48 October 2013

- #47 September 2013

- #46 June 2013

- #45 May 2013

- #44 April 2013

- #43 March 2013

- #42 February 2013

- #41 January 2013

- #40 December 2012

- #39 November 2012

- #38 October 2012

- #37 September 2012

- #36 July 2012

- #35 May 2012

- #34 April 2012

- #33 March 2012

- #32 February 2012

- #31 January 2012

- #30 December 2011

- #29 November 2011

- #28 October 2011

- #27 September 2011

- #26 June 2011

- #25 May 2011

- #24 April 2011

- #23 March 2011

- #22 January 2011

- #21 December 2010

- #20 November 2010

- #19 October 2010

- #18 September 2010

- #17 June 2010

- #16 May 2010

- #15 April 2010

- #14 March 2010

- #13 February 2010

- #12 January 2010

- #11 December 2009

- #10 November 2009

- #09 October 2009

- #08 September 2009

- #07 June 2009

- #06 May 2009

- #05 April 2009

- #04 March 2009

- #03 February 2009

- #02 January 2009

- #01 December 2008

- #00 November 2008

- Collectivism

- Care

- Gamification

- Exhaustion

- Desert

- Resurrection

- Ghosts

- World-Making

- Fermentation

- Exception

- Grief

- Adrift

- Plastic

- Promiscuity

- Industry Queer

- Coolness

- Support Bubble

- Techno-body

- True Fake

- Loot and Looting

- Strike

- Withdrawal

- Togetherness

- Studentship

- Weather

- Trust

- Violence

- Breathe

- Dispersal

- Home

- Untimeliness

- Humus

- Synchronicity

- Love

- Desire

- Compulsion

- Dizziness

- Marbles

- Re-Membering

- Magic

- Rebirth

- Rest

- Autonomy

- Contamination

- Utopia

- Online

- Vulnerability

- Deception

- Energy

- Death

- Resilience

- Language

- RentStrike

- Healing

- Work

- Silence

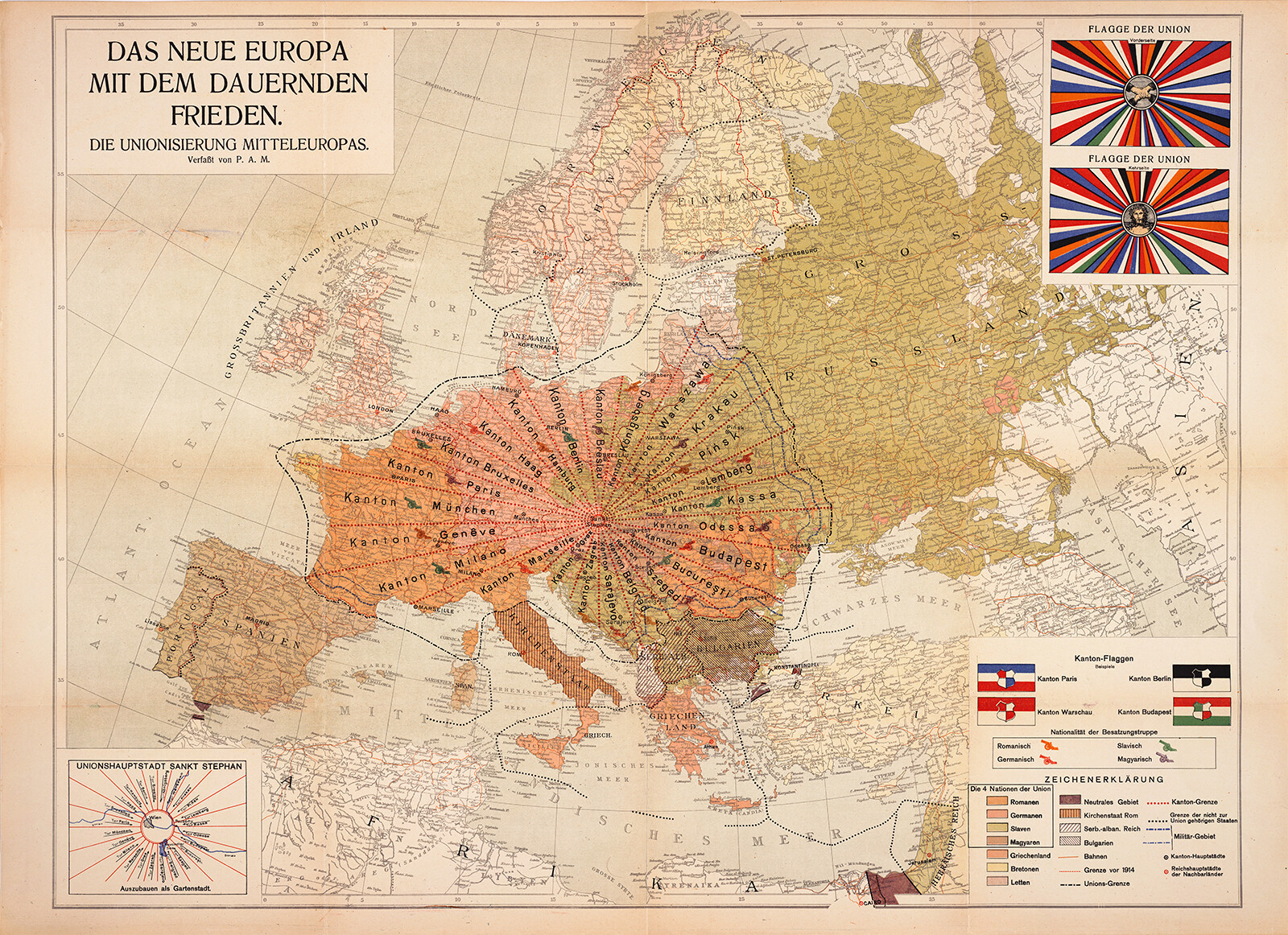

- Borders

- Closeness

- Contagion

- Volumetrics

- End

- Pathologies

- Tomorrow

- Absence

- Touch

- Crisis

- Apocalypse

- BloodBlooms

- Movement

- Corporeality

- Hospitality

- “Performativity”

- Masks

- Unlearning

- Ruins

- Time

- Contactless

- Shadow-Time

- Immunity

- Human Rights

In past centuries, almost every philosopher was addressed according to nationality, and a new school of thought was often prefixed with a nationality. A thinker can only go beyond the nation-state by becoming heimatlos, that is to say, by looking at the world from the standpoint of not being at home. This doesn’t mean that one must refrain from talking or thinking about a particular place or a culture; on the contrary, one must confront it and access it from the perspective of a planetary future.

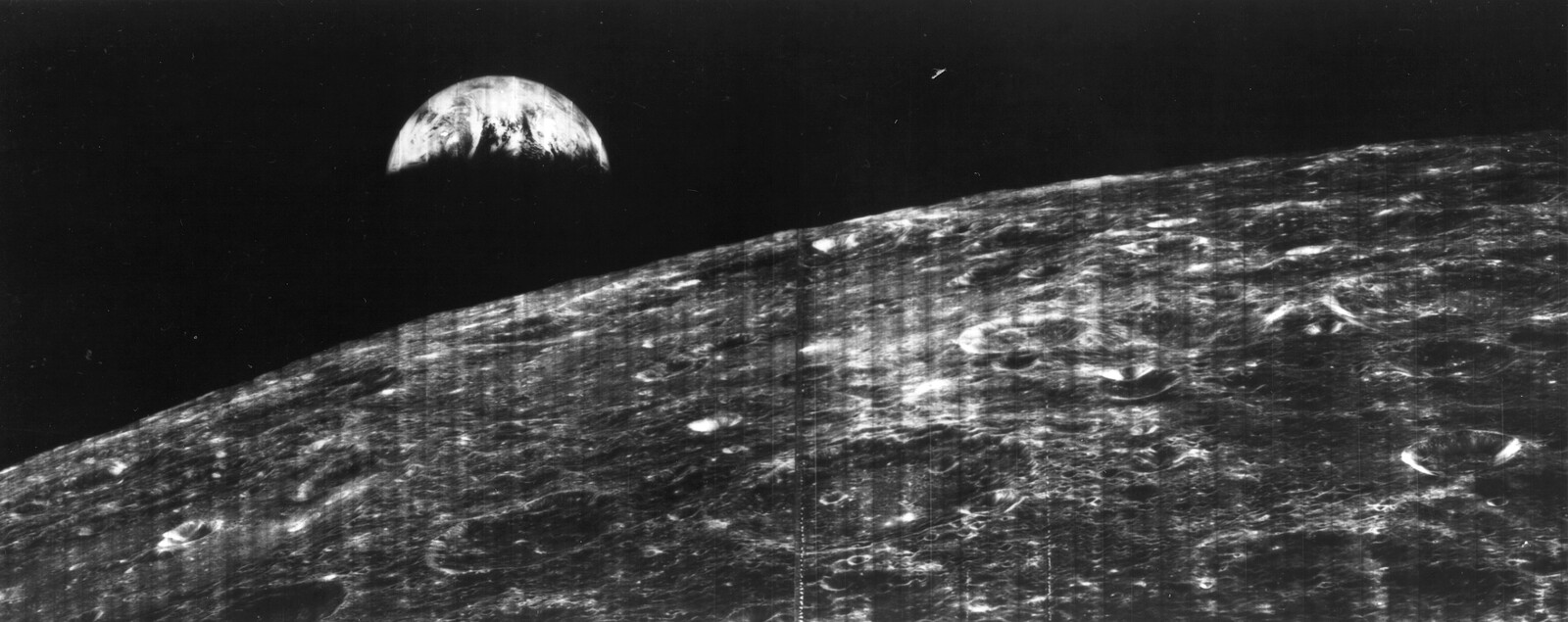

In the twenty-first century, we can easily sense that this process of destruction and recreation is only accelerating rather than slowing down. The longing for Heimat will only be intensified instead of being diminished; the dilemma of homecoming can only become more pathological. In fact, two opposed movements are taking place at the same time: planetarization and homecoming. Capital and techno-science, with their assumed universality, have a tendency toward escalation and self-propagation, while the specificity of territory and customs have a tendency to resist what is foreign.

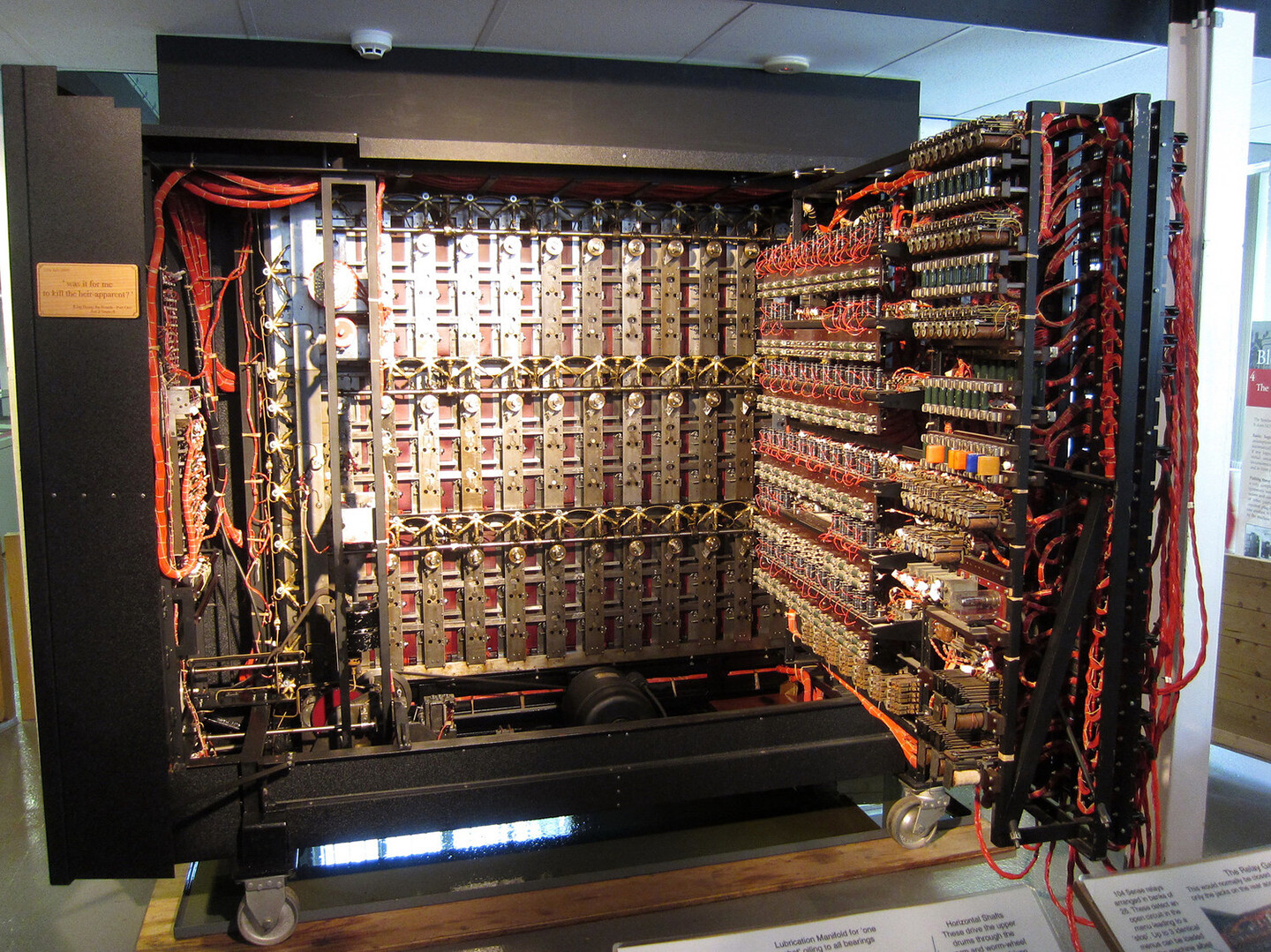

Today’s humans fail to dream. If the dream of flight led to the invention of the airplane, now we have intensifying nightmares of machines. Ultimately, both techno-optimism (in the form of transhumanism) and cultural pessimism meet in their projection of an apocalyptic end.

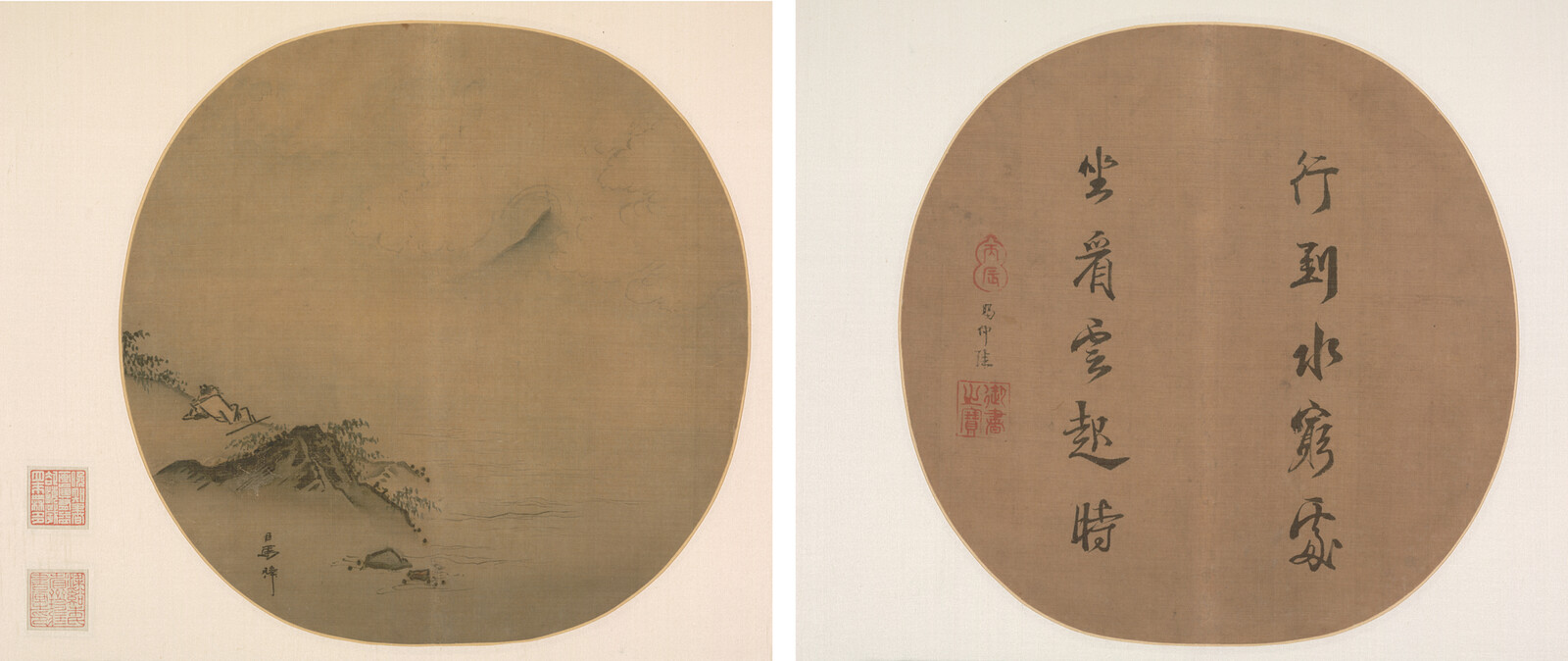

Cybernetic logic is always about the pursuit of a telos. So if you ask artificial intelligence to write a poem, it is always determined by an end, and this end is calculable. But in what I call tragist logic or shanshui logic we find a similar recursive movement, yet the end is something incalculable. So how can we relate back the question of the incalculable to our discussion of the use of artificial intelligence?

Maybe there are other ways of overcoming modernity that remain important for us today. War is not the most desirable thing, though it is always a possibility as long as the sovereign state remains the only reality of international politics, since sovereignty presupposes the possibility of war.

If, since Walter Benjamin—or even since the avant-garde before Benjamin—we have been trying to ask how technology changes the concept of art, as you find in Duchamp, can we now turn the question around and ask how art can transform technology? I think this is an important question not only in a conceptual sense, but also in a diplomatic one. If you were to talk to an engineer about an art project, how would you talk to them? Do you simply want to import this or that technology to create some kind of a new experience? Or do you want to influence how technology is made, how technology is conceived, how technology ought to be developed? I think we can also turn the question around further by asking: How can art contribute to the imagination of technological development?

Sense-making (Besinnung) cannot be restored through the negation of planetarization. Rather, thinking has to overcome this condition. This is a matter of life and death. We may want to call this kind of thinking, which is already taking form but has yet to be formulated, “planetary thinking.”

How can I believe that Bernard has already left us? It is true that he has left, but I don’t believe it and I will not believe it. Since I woke up on August 7 and read about the death of Bernard Stiegler, I have listened to his voice on the radio and felt Bernard’s presence, his generosity, his warm greetings and smiles. I haven’t been able to stop my tears. I was on the phone with Bernard just a week ago, talking about an event in Arles at the end of August and our future projects. Bernard’s voice was weaker than usual, but he was positive. He complained that his mobile didn’t work and his printer was broken, and he wasn’t able to buy new ones online because he needed a verification code sent to his mobile. Yet he continued to write. On August 6, I felt unusually weak myself. My belly was aching. This happened to me two years ago when my friend and copyeditor committed suicide. I dragged my body to the post office to send Bernard some Korean ginseng I had promised him a while ago, but the post office was closed due to COVID-19. When I got home, I thought to send him a message telling him that two special journal issues I edited, and that he took part in, were about to come out. I now regret that I didn’t manage to tell him, since I no longer have the chance to talk to him anymore.

For Jacques Derrida (whose widow, Marguerite Derrida, recently died of coronavirus), the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center marked the manifestation of an autoimmune crisis, dissolving the techno-political power structure stabilized for decades: a Boeing 767 was used as a weapon against the country that invented it, like a mutated cell or virus from within. The term “autoimmune” is only a biological metaphor when used in the political context: globalization is the creation of a world system whose stability depends on techno-scientific and economic hegemony. Consequently, 9/11 came to be seen as a rupture which ended the political configuration willed by the Christian West since the Enlightenment, calling forth an immunological response expressed as a permanent state of exception—wars upon wars. The coronavirus now collapses this metaphor: the biological and the political become one. Attempts to contain the virus don’t only involve disinfectant and medicine, but also military mobilizations and lockdowns of countries, borders, international flights, and trains.

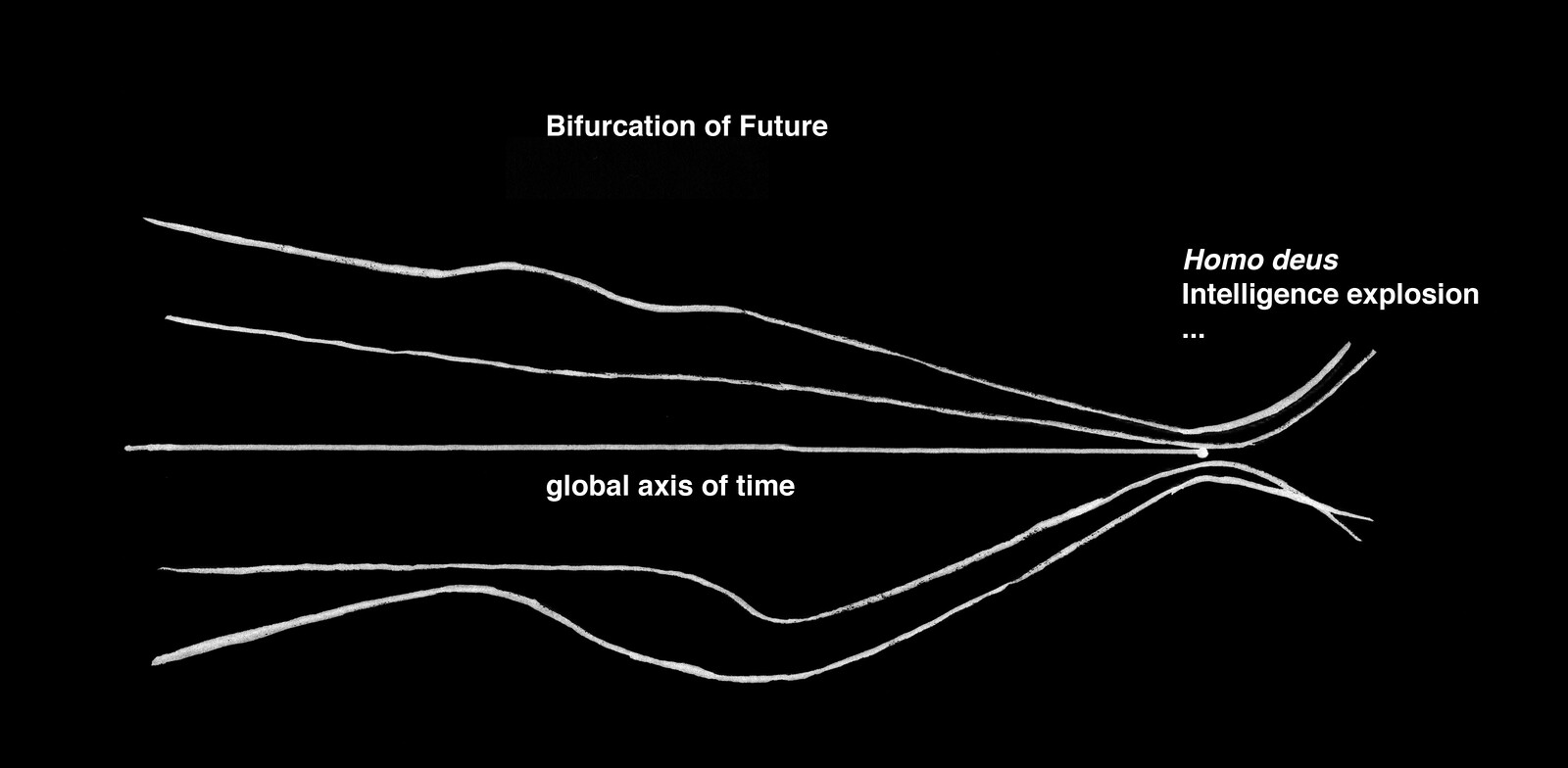

On the other hand, we may understand Kissinger’s end-of-Enlightenment claim as marking the full realization of a single global axis of time in which all historical times converge into the synchronizing metric of European modernity. It is the moment of disorientation—a loss of direction as well as of the Orient in relation to the Occident. The unhappy consciousness of fascism and xenophobia arises from this inability to orient: as a response, it offers an easy identity politics and an aestheticized politics of technology. More broadly, such a disorientation can be seen as a desirable and necessary deterritorialization of contemporary capitalism, which facilitates accumulation beyond temporal and spatial constraints. War is the technique of disruption par excellence, vastly more effective than Uber and Airbnb.

Dao is not a thing. It is not a concept. It is not the différance. In the Cixi of YiZhuan (易傳‧繫辭), Dao is simply said to be “above forms,” while Qi is what is “below forms.” We should notice here that xin er shang xue (the study of what is above forms) is the word used to translate “metaphysics” (one of the equivalences that must be undone). Qi is something that takes space, as we can see from the character and also read in an etymological dictionary—it has four mouths or containers and in the middle there is a dog guarding the utensils. There are multiple meanings of Qi in different doctrines; for example, in classic Confucianism there is Li Qi (禮器), in which Qi is crucial for Li (a rite), which is not merely a ceremony but rather a search for unification between the heavens and the human. For our purposes, it will suffice to simply say that Dao belongs to the noumenon according to the Kantian distinction, while Qi belongs to the phenomenon. But it is possible to infinitize Qi so as to infinitize the self and enter into the noumenon—this is the question of art.

Regardless of which Christian sect we ascribe it to, universalism remains a Western intellectual product. In reality there has been no universalism (at least not yet), only universalization (or synchronization)—a modernization process rendered possible by globalization and colonization. This creates problems for the right as well as the left, making it extremely difficult to reduce politics to the traditional dichotomy. The reflexive modernization described by prominent sociologists in the twentieth century as a shift from the early modernity of the nation-state to a second modernity characterized by reflexivity seems to be questionable from the outset.