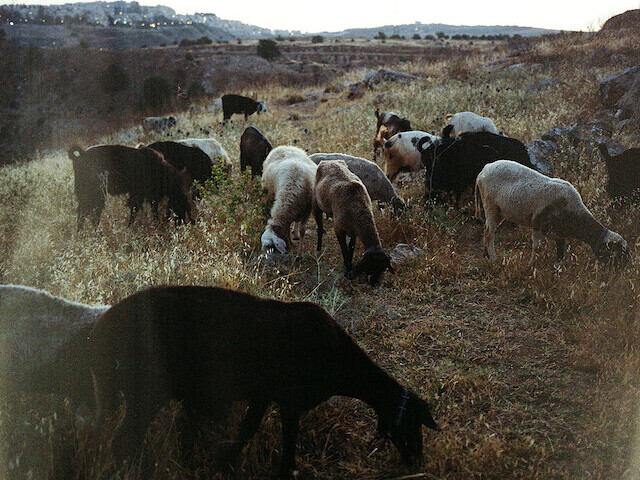

Za’atar, the most widely used herb in any Palestinian (or Levantine) kitchen, was the first edible plant to be red-listed in Israeli law books. It was 1977 when Israel’s then minister of agriculture, Ariel Sharon, declared it a protected species, effectively placing a total ban on the tradition of collection, punishable by hefty fines and up to three years in prison. There were no official scientific studies published to legitimize the ban; rather, it was presented as a “gut” decision. Rumor has it that Sharon caught onto the symbolic value of za’atar after the 1976 siege of Tel al-Za’atar, Arabic for “thyme hill.” This Palestinian refugee camp, established north of Beirut in 1948, suffered one of the worst massacres of the Lebanese Civil War in a battle fought between the armed factions of the PLO and the Christian Lebanese Militia—the very same phalangist militia with whom Sharon would form an alliance in the 1982 massacre of Sabra and Shatila.

Wars have evolved to many more frames per second in the years since the war on Iraq began (and have indeed accelerated because of that war), and we continue to participate in them no matter how undecided, baffled, or distant we are towards them—and no matter who “we” are (just yet). We participate in war because we consume its cruel images, and often at a mediated distance. The Lebanese writer and translator Lina Mounzer profoundly wrote in 2015: “I have buried seven husbands, three fiancés, fifteen sons, and a two-week-old daughter … I have watched my city, Maarrat al-Numan, burn, I have watched my city, Raqqa, burn, I have fled Aleppo … All this I have watched from my living room in Beirut.”

Joana Hadjithomas films from her plane landing in İzmir to show a clear aerial image of its urban spaces and its seashore, a reflection of the imaginary cartography of the place shown to her as a child. The camera often returns to the sea and waves that connect Etel’s living room to Joana’s first visit to the city. The gaze panning the horizon and the seashore reflects the catastrophe that prompted their estrangement from the place. ISMYRNA often depicts the landscape of İzmir as well as several old and current maps. As film subjects, the mountains, the sea, the seashore, and even the urbanization of İzmir seem like such innocent bystanders.

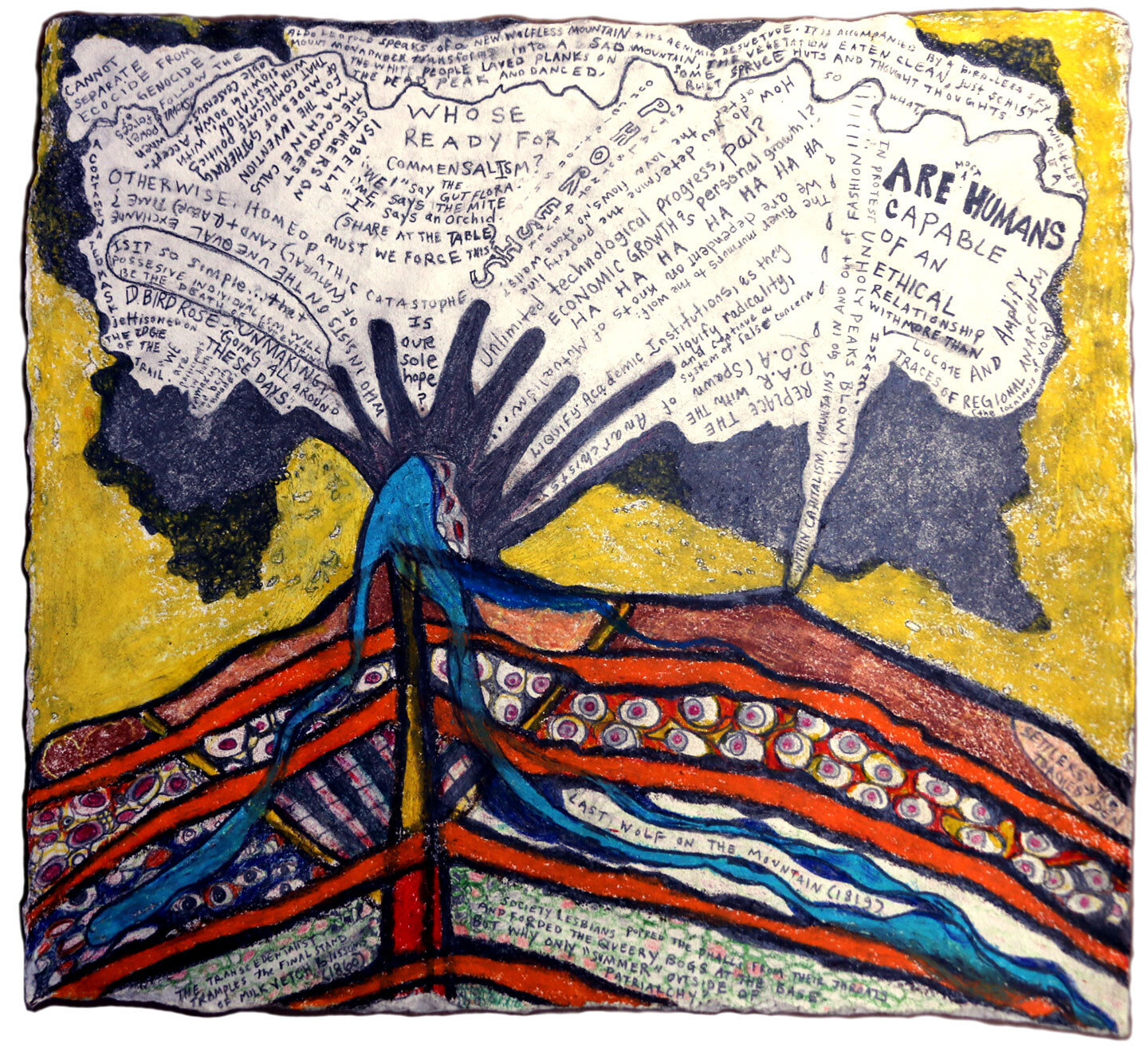

Supposedly, one of the many “functions” of art is to heal the ruptures of history, and to “puncture” a whole in the membrane of the future, so as to render its advent felt in the present. In other words, artworking is to invent the sense of a shared time, across geographical expanses and ideological divides. How come today’s art, or philosophy, doesn’t achieve this? The underlying question is: How come “art” or “philosophy” doesn’t prevent violence? Ultimately, artists and philosophers are reproaching each other for the failure in solving problems that belong to the fields of medicine, education, political science, architecture, history, design, engineering, psychology, anthropology, genocide studies, etc. Is it only art or philosophy that fails in the face of the Rwandan genocide? Haven’t politics, technology, science, journalism, and the list is endless, also relapsed? What aspect of living doesn’t face its limit under such marks of death? I have no illusions that mere philosophers, or artists, are able to save the world! Why reproach the inadequacies of entire societies solely upon the ethics and the aesthetics of two cultural bodies?

Good Hindus, emboldened by Karma and the theory of reincarnation, get more than one chance at the game of life. Death may be inevitable, but for the Holinesses, such as the eminence of the Juna Akhada, it is not irreversible. You may die today, but the Karmic debt you incur by voting for Narendra Modi will certainly bring you back tomorrow. So why not, if you want it stronger, dip a little longer in the Kumbh cauldron? You live, you die, you live, you pass on an infection, you kill some more, you die, you live, you die, and so on.

Those who make it possible to really live as a trans woman are rarely those who are our representatives to the other, and still less those who appoint themselves among us as the police of our supposed collective identity. Those who make it possible are artists. Not fine artists necessarily, nor writers of “fine writing.” They might work in minor, vernacular forms. They might just be artists of trans life itself. They might be undetectable outside of our little covens of care. They make up stories or images or gestures that elude the limits of what they, and we, were handed. Making it up as they go.

These days, “fem” has come to be used as a synonym for conventional femininity, and “queer” has come to mean “lesbian, gay, and bisexual” in a spicier tone of voice. This draining of political meaning from words we’ve called home has affected trans worlds less deeply than cis ones up to this point, but it is underway among us as well.

Somewhere on the west coast, the third neighbor over doesn’t care about Maroon history… / and you’ve gone and forced his hand. This whole city started with an arranged strata / matrimony. Middleclass-ness, if the sky were to belong in a poem. The seat next to me is a place / of panic.

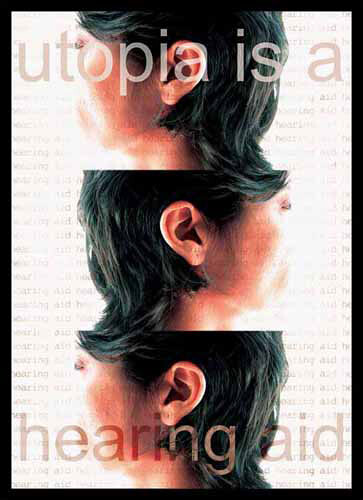

A photo hides more than it shows, which is merely the physical and reflective light of the world: bodies in a place, scars on skin, a wall in a landscape, a person holding a book, fireworks at night, trees, four people hugging each other in a joyful moment, a boy looking at his drawing, a policeman shooting at demonstrators. We have seen all of that, we have photographed it, but what about the unphotographable violence that goes through the image without leaving a trace in it, the systematic violence that is normalized within life itself, the pain of the forest, the law that doesn’t allow your child to get a birth certificate, the fear of being profiled, of not being allowed to travel, and the bureaucracy of everyday life?

Diasporic existence is a refusal, the refusal to choose between two worlds. This refusal assumes a singular form when the two worlds are in conflict. It summons a whole vital economy that contests a geopolitics founded on the logic of predator and victim.

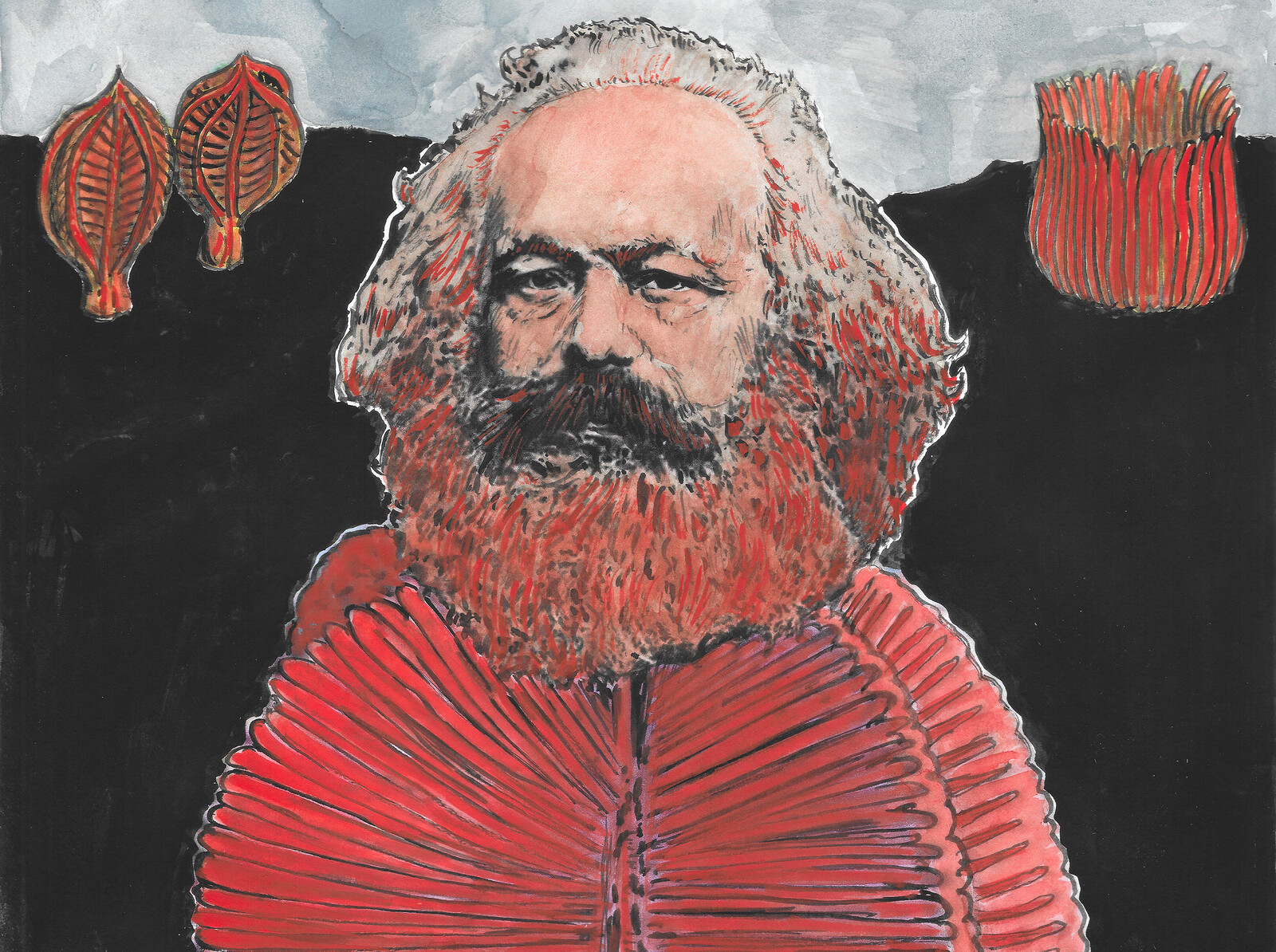

Decades of capitalist propaganda has reduced the notion of collectivization to Stalinist terror. This flattening of the term dismisses the breadth of forms that collectivization can take: from nationalizing communal resources and production, to other-than-human redistribution efforts to establish comradely ecologies. It is therefore essential to explore the collectivized imaginaries and practices—collectivizations, in the plural—that make egalitarian forms of life imaginable and actionable.

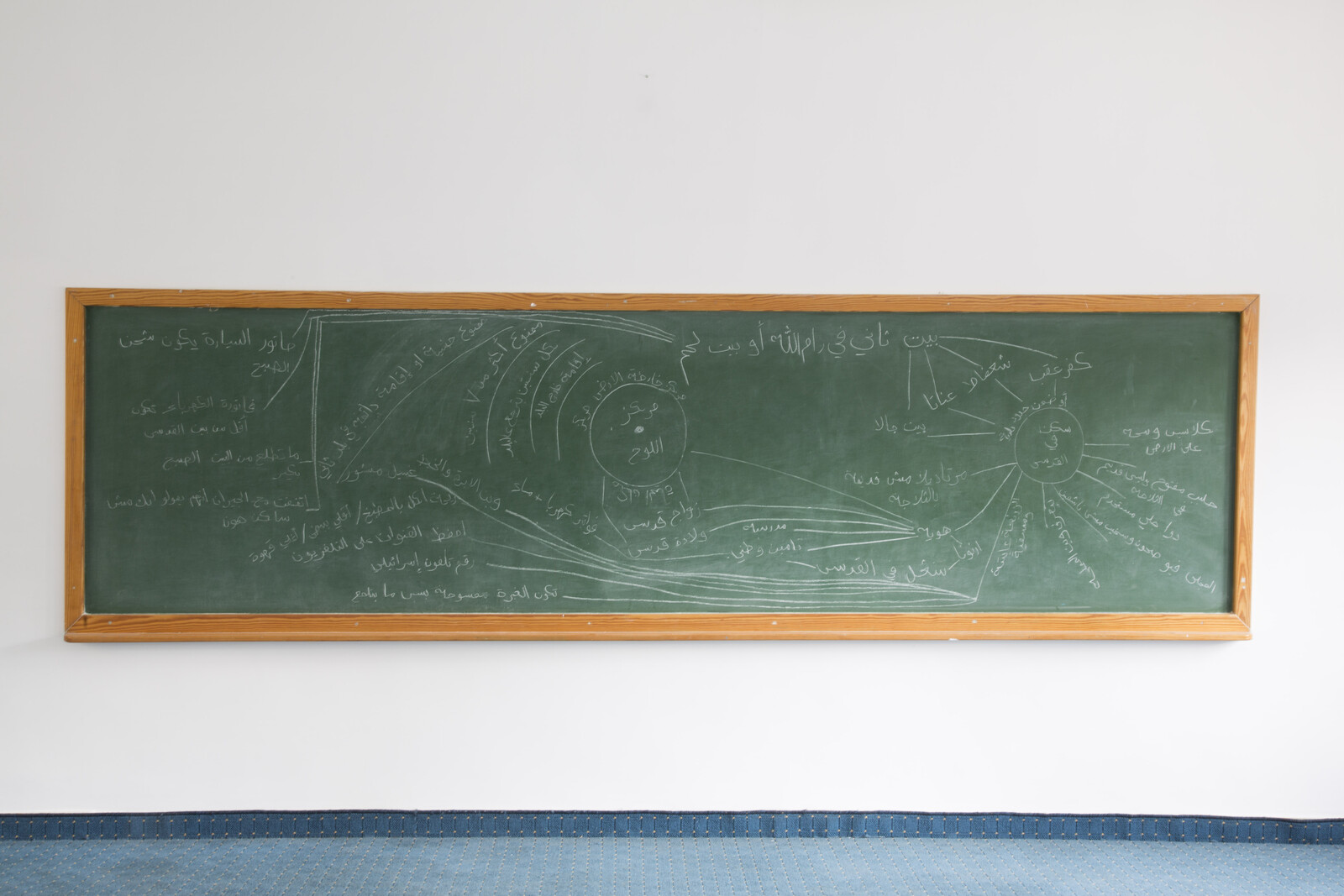

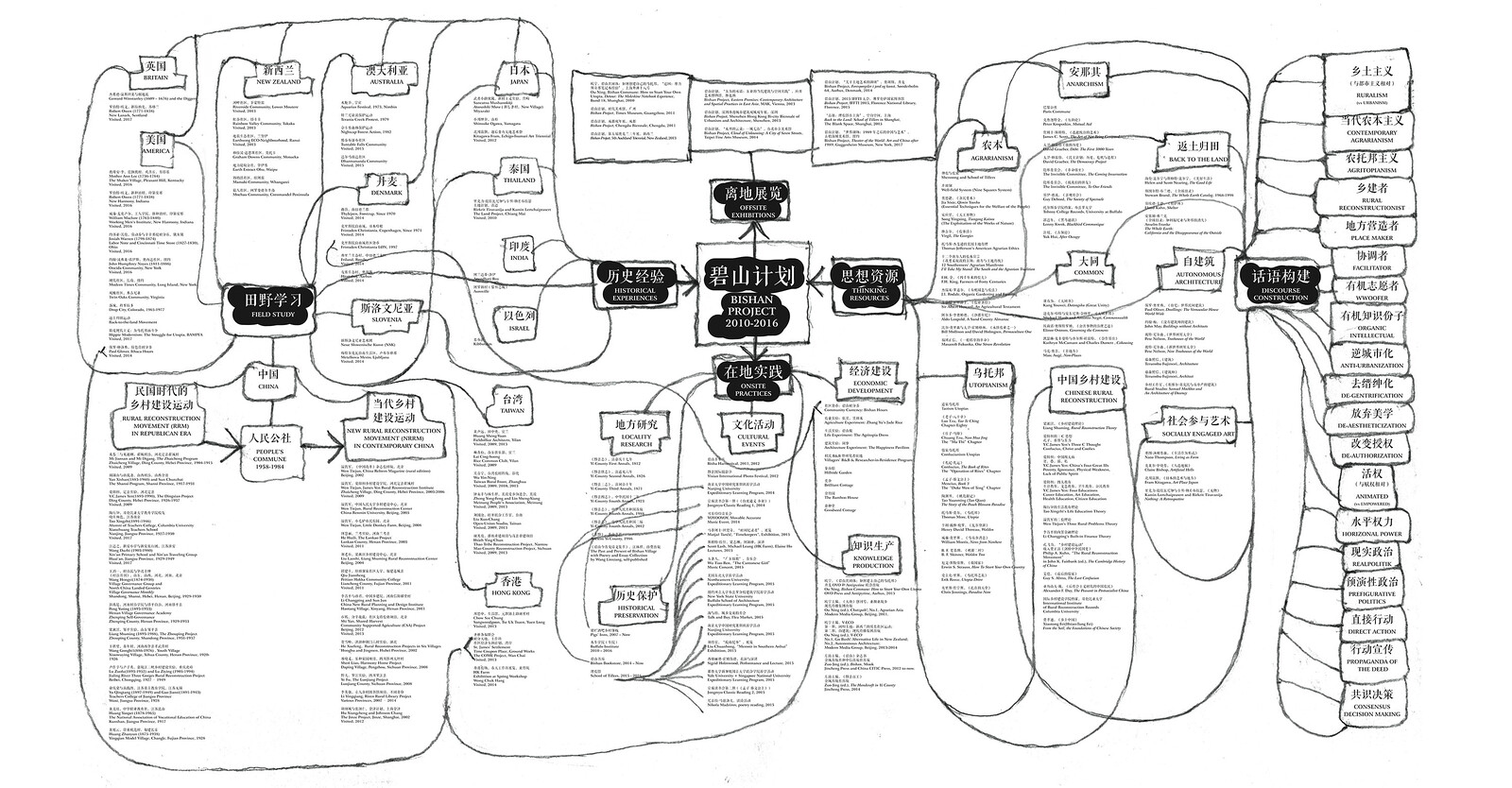

Farmers are not “human waste” eliminated by the modernization process, as many people think. Their “cunning” wisdom is often unexpected. Their “brain mine” (to use James Yen’s term) is rich, but ignored. The problem of contemporary Chinese farmers is that they live at the bottom of an “authority-driven” society where state power permeates in a totalizing way. These farmers can neither return to the “autonomy of the landed gentry” of the era of monarchy, in which “imperial power extended down only to the county level,” nor can they speak through the electoral system like American farmers. The space to realize their potential is very limited. As an outsider with neither power nor capital, all I can do in the countryside is use my own cultural resources to improve farmers and villagers’ visibility in society, broaden their contact with the outside world, and build platforms within my ability to let them give full play to their intelligence. Under limited, realistic conditions, so-called “empowerment” and “moralization” are all extravagant to me, and they are also part of an elite rhetoric that I oppose. I prefer the words “mutual aid,” “mutual learning,” and “communal life.”

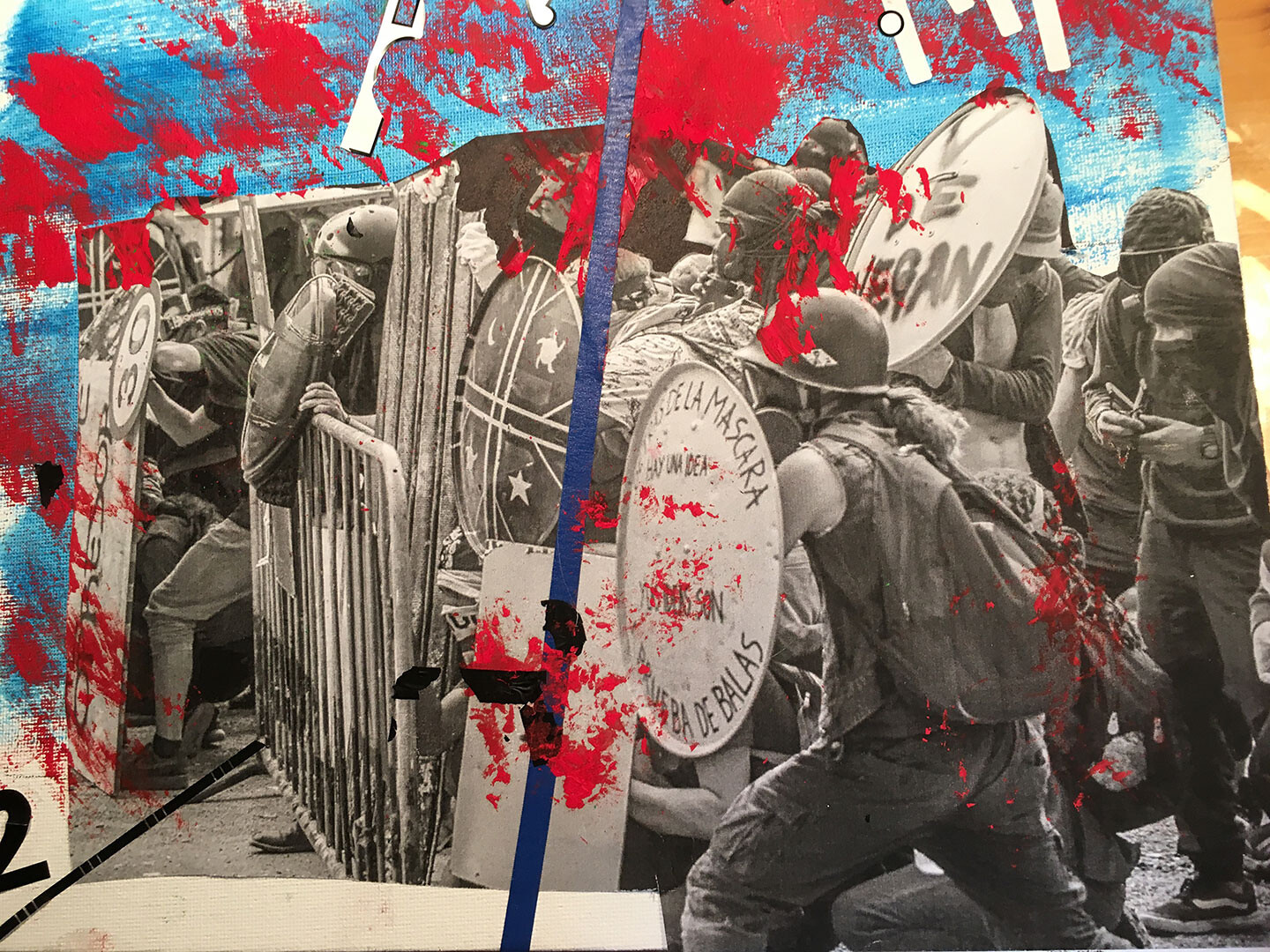

How can we avoid amplifying our failures at the expense of what we achieve? The question is not only tactical, but also interpretive. When we evaluate our collective actions for their concrete material effects—for the damage they do at the human scale—we are immediately confronted with our powerlessness in the face of our enemy. This enemy not only holds the monopoly on legitimate violence (and is not afraid to use it), but also knows how to weather the storm. Capitalists build pushback into their budgets. They take out insurance policies to cover broken windows, arson, and lost profits. In advance of scandal, they contract public relations firms to protect their brands. Faced with the cunning and brute power of the capitalist state, how are we to see our uprisings as anything but futile tantrums—proof of our incapacity to move from rebellion to revolutionary change? The answer is in recognizing the ways that our concrete actions in the material world contribute to the language in common, through which we build and express our difference.

There is said to be a universal hum. An imperceptible vibration producing a sound ten thousand times lower than can be registered by the human ear. It can be measured on the ocean’s floor, but its source is not exactly known: perhaps the hush of oceanic waves, perhaps the turbulence in the atmosphere, or the far bluster of planetary storms.

The world is divided, as Bruno Latour puts it, not only in relation to environmental politics but also, and even more sharply, in relation to sexual and reproductive politics. A new hot war divides the world into two blocs: on one side, the techno-patriarchal empire and, on the other, the territory where it is still possible to negotiate gestational sovereignty.

Now, in strata 2020, after the cytokine squall—both national and personal—parts of my brain seem to have floated away from one another … and I am suspended in an immensity that is something distinctly different from “being Someone.” Could this be a backdoor through and out of capitalism? For all whites to cease being Someone? I paw at the ground. The exit should be a trapdoor. A chute with no return.

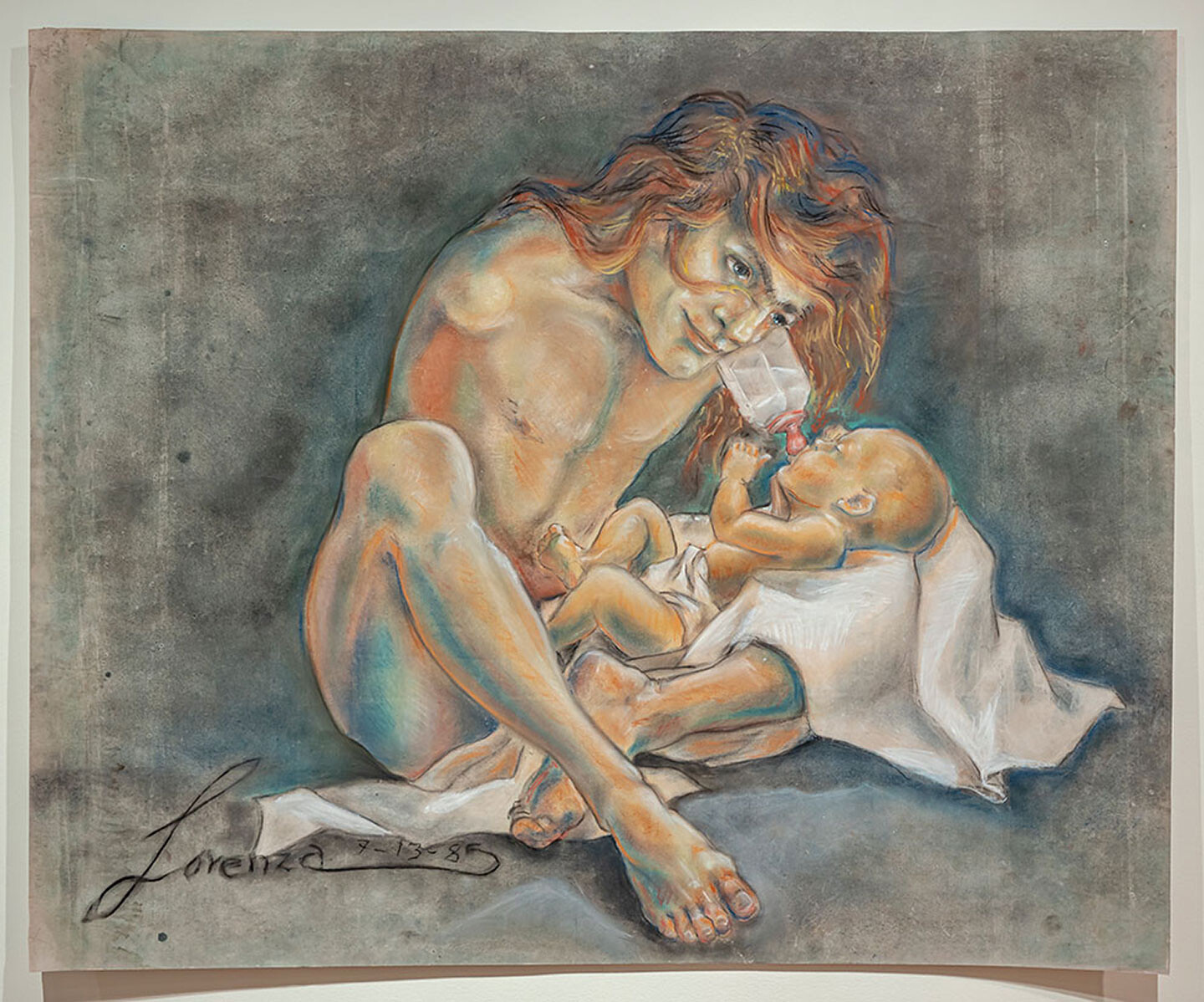

“The everyday “miracle” that transpires in pregnancy, the production of that number more than one and less than two, receives more idealizing lip-service than it does respect. Certainly, the creation of new proto-personhood in the uterus is a marvel artists have engaged for millennia (and psychoanalytic philosophers for almost a century). Most of us need no reminding that we are, each of us, the blinking, thinking, pulsating products of gestational work and its equally laborious aftermaths. Yet in 2017 a reader and thinker as compendious as Maggie Nelson can still state, semi-incredulously but with a strong case behind her, that philosophical writing about actually doing gestation constitutes an absence in culture.

If we begin with the understanding that police protect property and their owners, we can expect this to be its primary consequence: those who have very little property in a community are bound to experience a frequency of bad encounters with law enforcement that is much higher than those who have a lot of property. And so it is. What we find in the US, the world’s top ownership society for the past hundred years, is a vast jail, prison, and parole system filled with men and women who do not own much of anything. From this fact, which links poverty to the business of policing, we also find an explanation for the overrepresentation of black Americans (who make up about 13 percent of the general population) in the US’s state prisons (they make up 40 percent of the penal population).

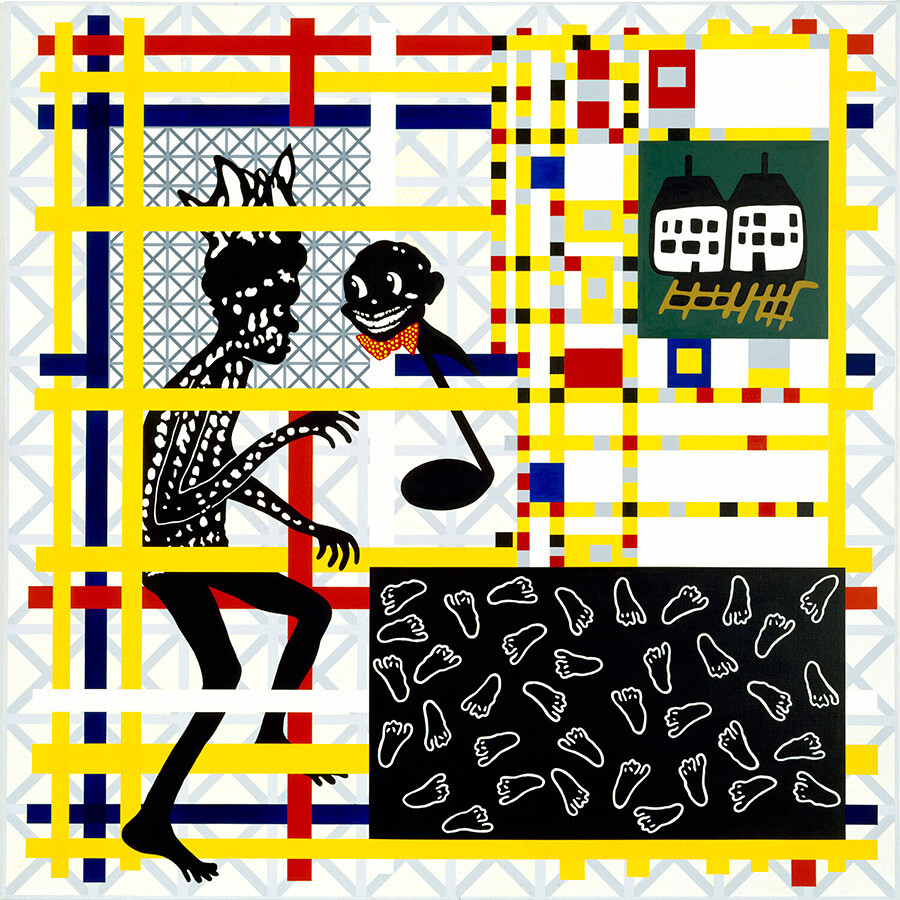

As a settler-colonist, it’s important to consume—to develop … consummate taste … a taste for the other, for the unknown, for the new. It’s important to consume Art … Art, especially the kind conjuring nostalgic memories, can relax you, can lubricate your voyage back toward a primal confidence, to your intuition, to your privilege, to your influence, to be influenced.

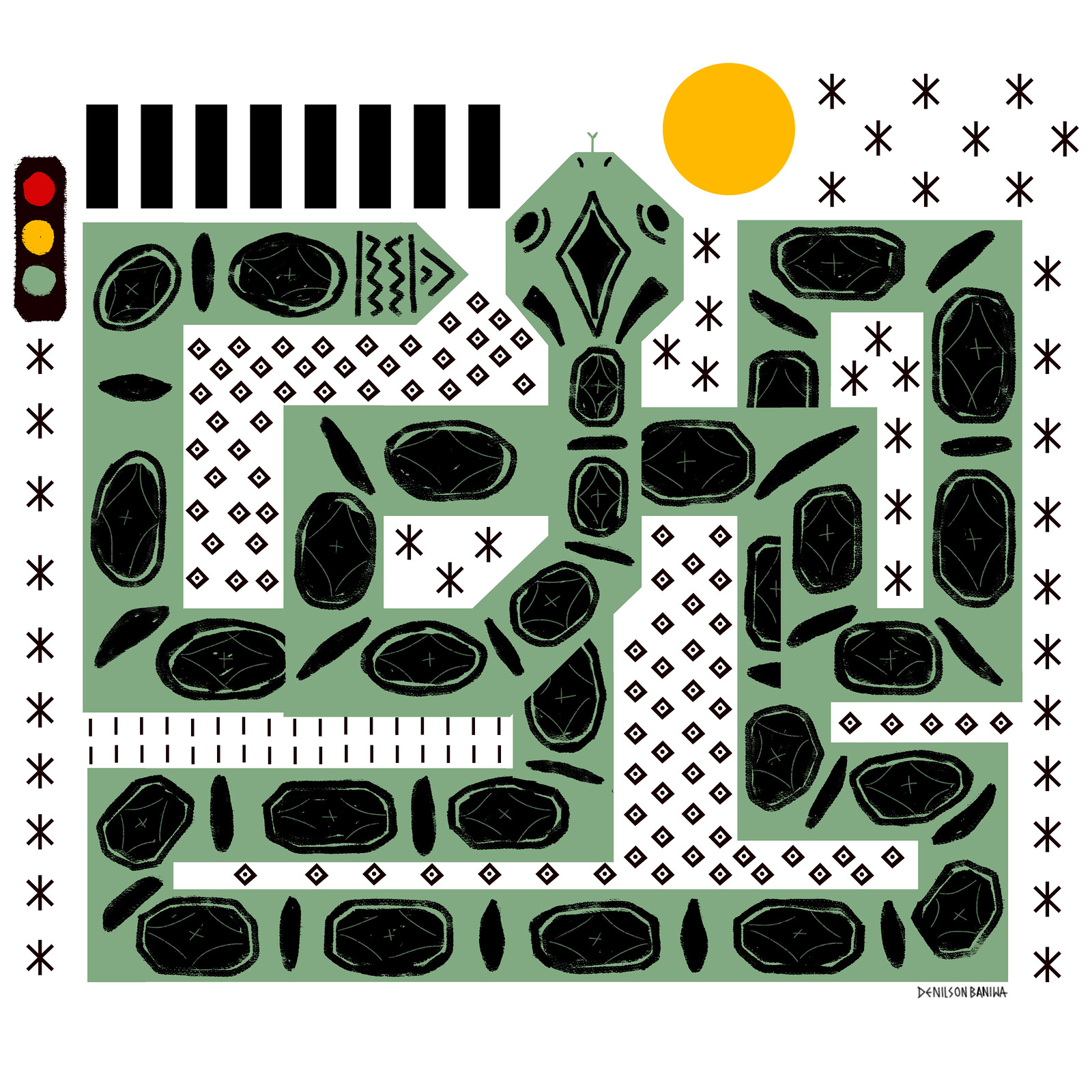

The Amazon rainforest is a monument. A monument built over thousands of years. The ecology of that place in motion creates shapes, volumes—disperses all that beauty. The Amazon rainforest, the Atlantic coastal forest, the Serra do Mar, the Takrukkrak are monuments that have, for us, the power to open a portal that accesses other visions of the world. The forest provides this. And yet, despite its materiality—its body that can be felled, uprooted as wood—the forest is not seen. In Brazil, there are cities that UNESCO has declared the cultural patrimony of humanity. Meanwhile, we destroy the Atlantic coastal forest, the Amazon rainforest. It’s a game of illusion.

Many argue that we should stop the movement of hundreds of thousands of art tourists around the globe, stop building pointless new offices, stop hosting so many exclusive presentations and dinners that serve no purpose other than self-celebration, and imagine how art could be one of many forms of care that contributes to the reproduction of human life (education, medicine, safety, different forms of knowledge, etc.). How else could it be possible for everyone to cultivate local artistic communities as ends in themselves? These are sensible proposals, but they lack the coherence and urgency of the demands being made to defund or abolish the police. What would any of this actually mean in practice? As a thought experiment, if we were to storm the Louvre or Hermitage again, what would we do with it? Anything? It’s also possible that palaces simply don’t lend themselves to democratic purposes.

Thanks to his ignorance and moral abjection, Donald Trump represents the true soul of America, the unmovable soul of a population formed by a never-ending sequence of exploitation, oppression, bullying, invasions, and abominable crimes. Nothing but this. There isn’t an alternative America, as many thought in the 1960s and ’70s. There are millions of women and men, mostly nonwhite, who have suffered from American violence, and especially at a certain point in the ’60s and ’70s, fought to reform America to become more human. They failed, because there is no way to reform a nation of bigots and killers.

Those progressives who are honestly confused by the concept of Black Power are in this state of confusion because they have not scientifically evaluated the present stage of historical development in relation to the stage of historical development when Marx projected the concept of workers’ power vs. capitalist power. Yesterday the concept of workers’ power expressed the revolutionary social force of the working class organized inside the process of capitalist production. Today the concept of Black Power expresses the new revolutionary social force of the black population concentrated in the black belt of the South and in the urban ghettos of the North—a revolutionary social force which must struggle not only against the capitalists but against the workers and middle classes who benefit by and support the system which has oppressed and exploited blacks.

In this symbolic and material economy, black and brown women’s lives are made precarious and vulnerable, but their fabricated superfluity goes hand in hand with their necessary existence and presence. They are allowed into private homes and workplaces. But other members of superfluous communities—such as the families and neighbors of these workers—must stay behind the gates, unless they are willing to risk being killed by state police violence and other forms of the militarization of green and public spaces for the sake of the wealthy. For these workers, the special permit to enter is based both on the need for their work and on their invisibility. Women of color enter the gates of the city, of its controlled buildings, but they must do it as phantoms. Racialized women may circulate in the city, but only as an erased presence.

It may be a cliché to say that the past, from the perspective of the present, looks like a field of ruins for the historian to excavate. But our past, then, was literally a field of ruins, not for excavation, but for reconstruction and pillaging. We emerged from the civil war into a violent reconstruction process, governed by a postwar settlement that was characterized by “state-sponsored amnesia,” and a genuine desire to forget past horrors. We rushed into the future because we had no past, at least no past that could provide us with a sense of belonging, meaning, or continuity with what had come before. We were the product of a rupture, and we became the vanguard by default.

Through its aesthetic liberation of things, ideas, and layers of time, art constructs imaginaries of interdependence, which in their own way contribute to a society of solidarity. Today, during this time of pandemic, we like to talk about us all being in the same boat, a metaphor that has replaced the catastrophic image of overcrowded boats of refugees crossing the Mediterranean. But the most powerful metaphor of the present time is the metaphor of the virus, which represents how everything influences everyone. But this is only our view of viruses, our exploitation of its properties. What viruses themselves think about this, nobody knows.

Along with being an index of democracy, art is also a lucrative niche for the global entertainment business. Art has thus become a form of consumable merchandise, destined to be used up. In this situation (diagnosed by Arendt and others in the 1960s), artists have either embraced this quality of art as merchandise (Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst), or rejected it in the name of politicization and criticality (Hans Haacke, Andrea Fraser, Hito Steyerl). With globalization, critical artists have been summoned to become useful by surrendering art’s (always partial) autonomy and taking up the task of restoring what has been broken by the system. So they denounce globalization’s collateral damage and contemporary art’s woeful conditions of production. They imagine a more just future, produce political imaginaries, disseminate counter-information, restore social links, gather and archive documents and traces for the “duty of memory,” etc. Perhaps, then, the prior role of the artist as a cultural vanguard has given way to a mandate to cultivate a feeling of political responsibility in spectators, in the name of self-representation and the representation of Enlightenment values.

For Jacques Derrida (whose widow, Marguerite Derrida, recently died of coronavirus), the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center marked the manifestation of an autoimmune crisis, dissolving the techno-political power structure stabilized for decades: a Boeing 767 was used as a weapon against the country that invented it, like a mutated cell or virus from within. The term “autoimmune” is only a biological metaphor when used in the political context: globalization is the creation of a world system whose stability depends on techno-scientific and economic hegemony. Consequently, 9/11 came to be seen as a rupture which ended the political configuration willed by the Christian West since the Enlightenment, calling forth an immunological response expressed as a permanent state of exception—wars upon wars. The coronavirus now collapses this metaphor: the biological and the political become one. Attempts to contain the virus don’t only involve disinfectant and medicine, but also military mobilizations and lockdowns of countries, borders, international flights, and trains.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, most of the shrines and likenesses of St. Wilgefortis were destroyed or left to deteriorate after the suppression of her sainthood during the Catholic liturgical purge of 1969. Art historian Ilse E. Friesen, who has done extensive research on the visual representations of Wilgefortis, states that the presence and worship of this saint became identified with anti-Christian, anti-Catholic, and deviant behavior. Her gender presentation was seen as grotesque and a denigration of Christ. Her suppression led to the loss of a saint that offered visibility to survivors of abuse and assault. We must also recognize this loss as a part of the continual erasure of violence against women, trans, and nonbinary people.In contemporary times she has also been interpreted by some as the patron saint of intersex people, asexual people, transgender people, and a powerful lesbian virgin.

Fragments from Edwards Said’s most personal and poetic work, After the Last Sky, are repurposed to create a new script that reflects on what it means now to be constructed as an “illegal” person, body, or entity. The script is turned into a song that is sung by the artists as multiple avatars. Created via a software program that generates avatars from a single image, the avatars in the video all come from images of people who participated in the “Great March of Return” that continues to take place regularly on the seamline in Gaza, an area that has been under physical siege since 2006. The relationship between fugitivity, fragility, and futurity becomes manifest in this field. The project uses low-resolution images that were circulated online; the avatar software renders the missing data and information in the original images as scars, glitches, and incomplete features on the characters’ faces.

_Section_of_human_placentaWEB.jpg,1600)