Energy

With the recent devaluation of oil came the sudden realization that the supply of fossil fuels has surpassed its demand. Until now our acquisition and extraction of energy sources have driven irreparable ecological and socio-political interventions across the globe. Our collective “sheltering in place” reveals an opportunity to imagine modes of living within nature beyond its mere thermodynamic rationalization. At a time of imposed isolation, steadfast connections have unexpectedly persisted between and among people, animals, and things—energies which global capitalism has typically obscured. Could this new perspective on contemporary life engender alternate energetic relations in the pandemic’s wake?

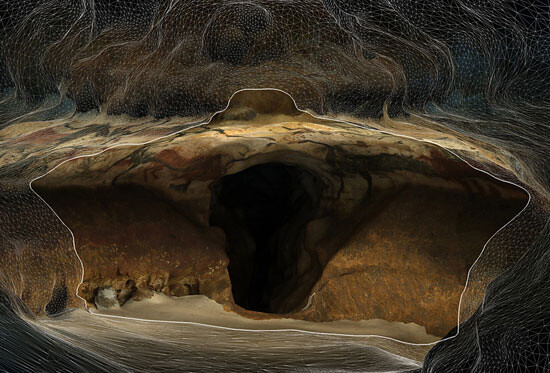

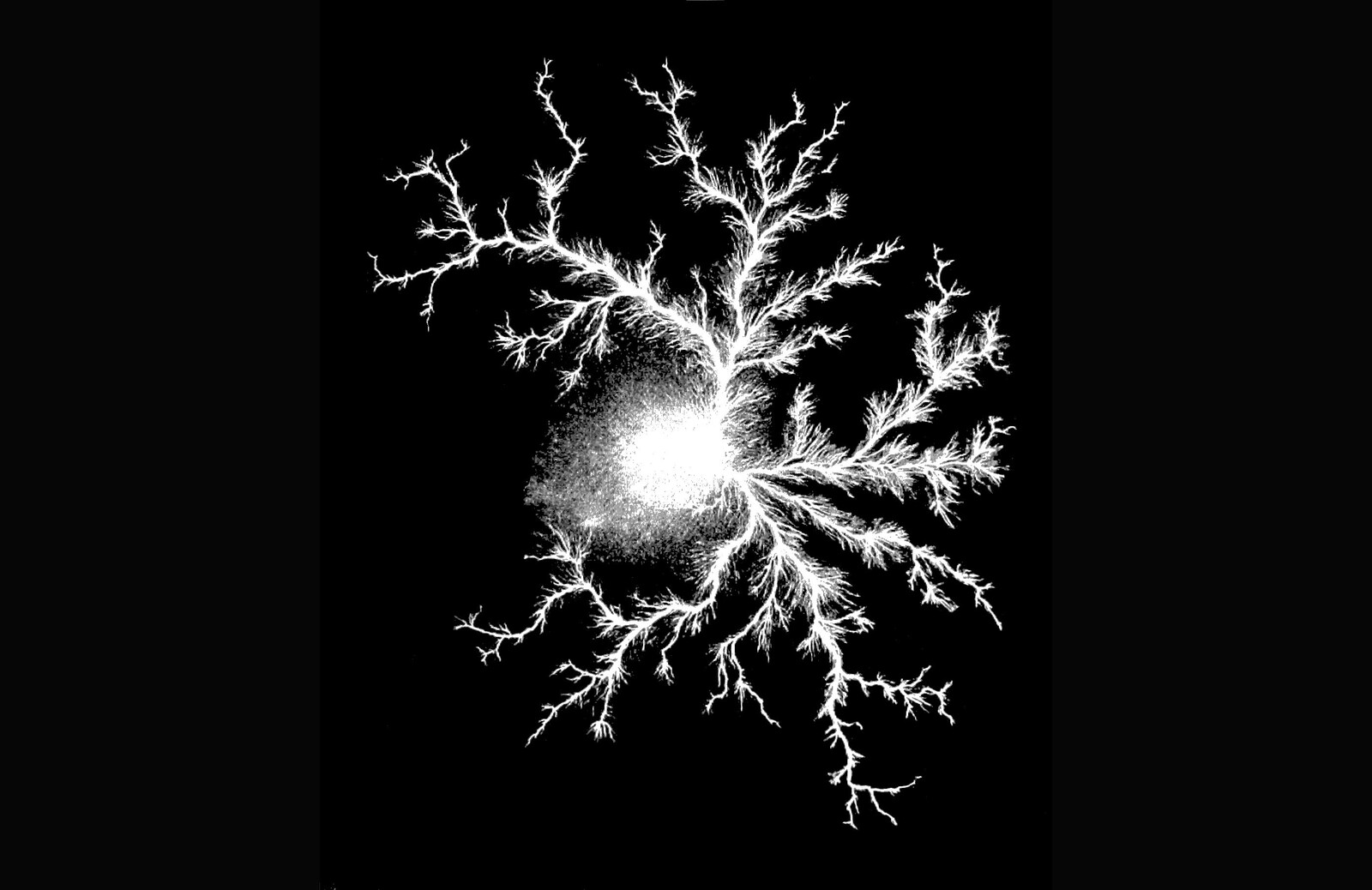

The Desert does not refer in any literal way to the ecosystem that, for lack of water, is hostile to life. The Desert is the affect that motivates the search for other instances of life in the universe and technologies for seeding planets with life; it colors the contemporary imaginary of North African oil fields; and it drives the fear that all places will soon be nothing more than the setting within a Mad Max movie. The Desert is also glimpsed in both the geological category of the fossil insofar as we consider fossils to have once been charged with life, to have lost that life, but as a form of fuel can provide the conditions for a specific form of life—contemporary, hypermodern, informationalized capital—and a new form of mass death and utter extinction; and in the calls for a capital or technological fix to anthropogenic climate change.

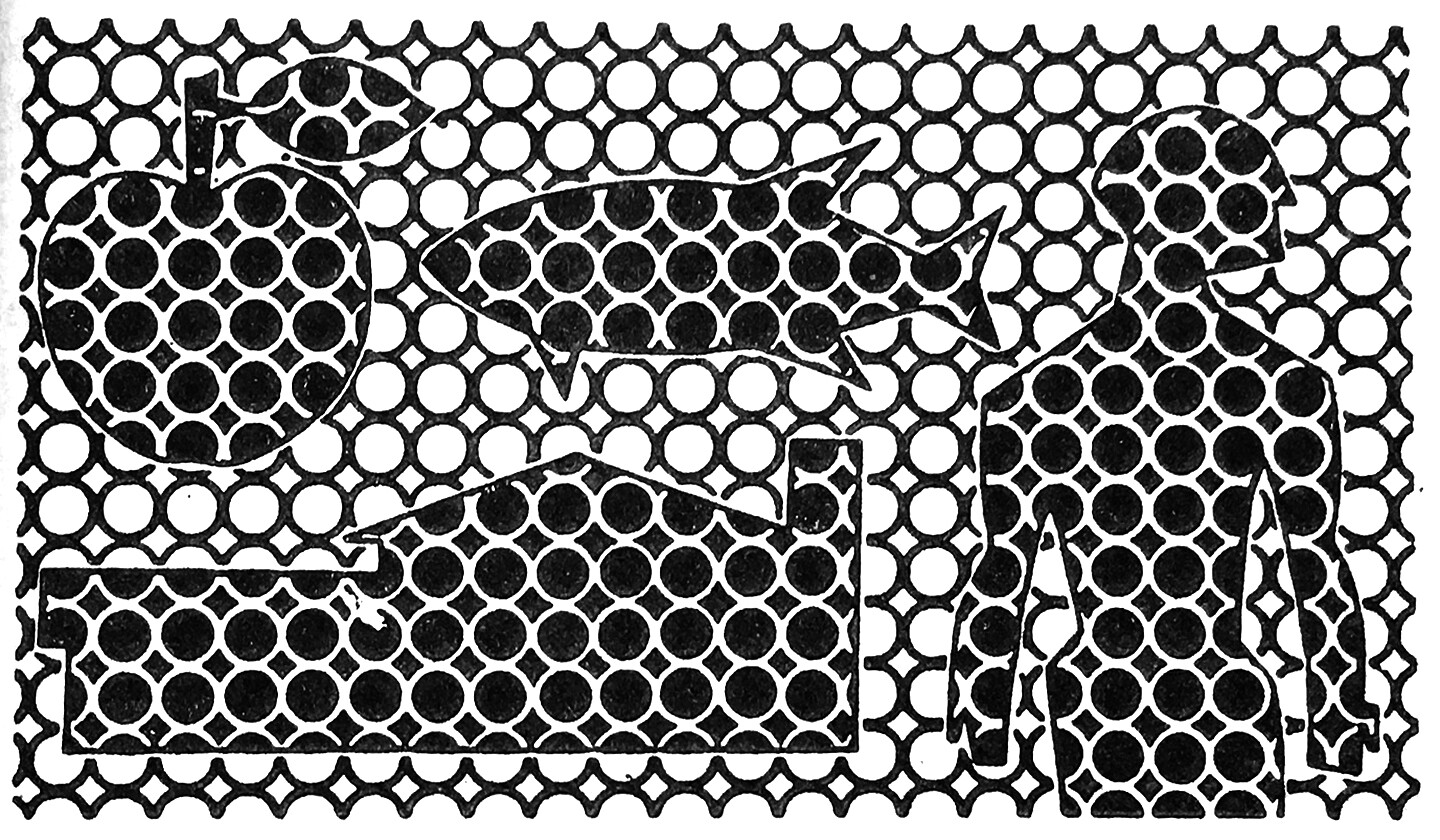

Subscendence affects things like nation-states, as huge and powerful as they appear. Subscendence is why you need a passport. It’s not to guarantee your identity, but to guarantee and prop up the identity of the state. Islamophobia sees Muslim terrorists as inevitably part of some larger, shadowy organization, while in the United States, white terrorists are always described as “lone wolves.” No matter how many of them shoot people in churches and outside abortion clinics and blow up government buildings, having trained in the Christian equivalent of an al-Qaeda training camp; no matter how many wolves there are, they are always seen as lone wolves, not as members of a pack. The concept that wholes are greater than the sum of their parts comes in ideologically handy because then Islamophobia can claim that Islamic terrorists are part of some emergent, shadowy whole, while white terrorists are individuals without a whole in sight.

Does climate change instantiate the “Kantian gap” between phenomenon and thing-in-itself, or rather actualize the Kantian correlation between mind and world, of which the thing-in-itself is the irrelevant remainder? As Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro have argued, “We can see the irony of our predicament as that of a catastrophic terrestrial objectivation of the correlation”—in other words, “human thought, materialized as a giant technological machine of planetary impact, effectively and destructively correlates the world.” If the productive abstractions of modern technoscience—this weaponized, transformative, operative logos—have remade the world, they have done so through the “actually existing linearity” of GDPs and CO2 levels.

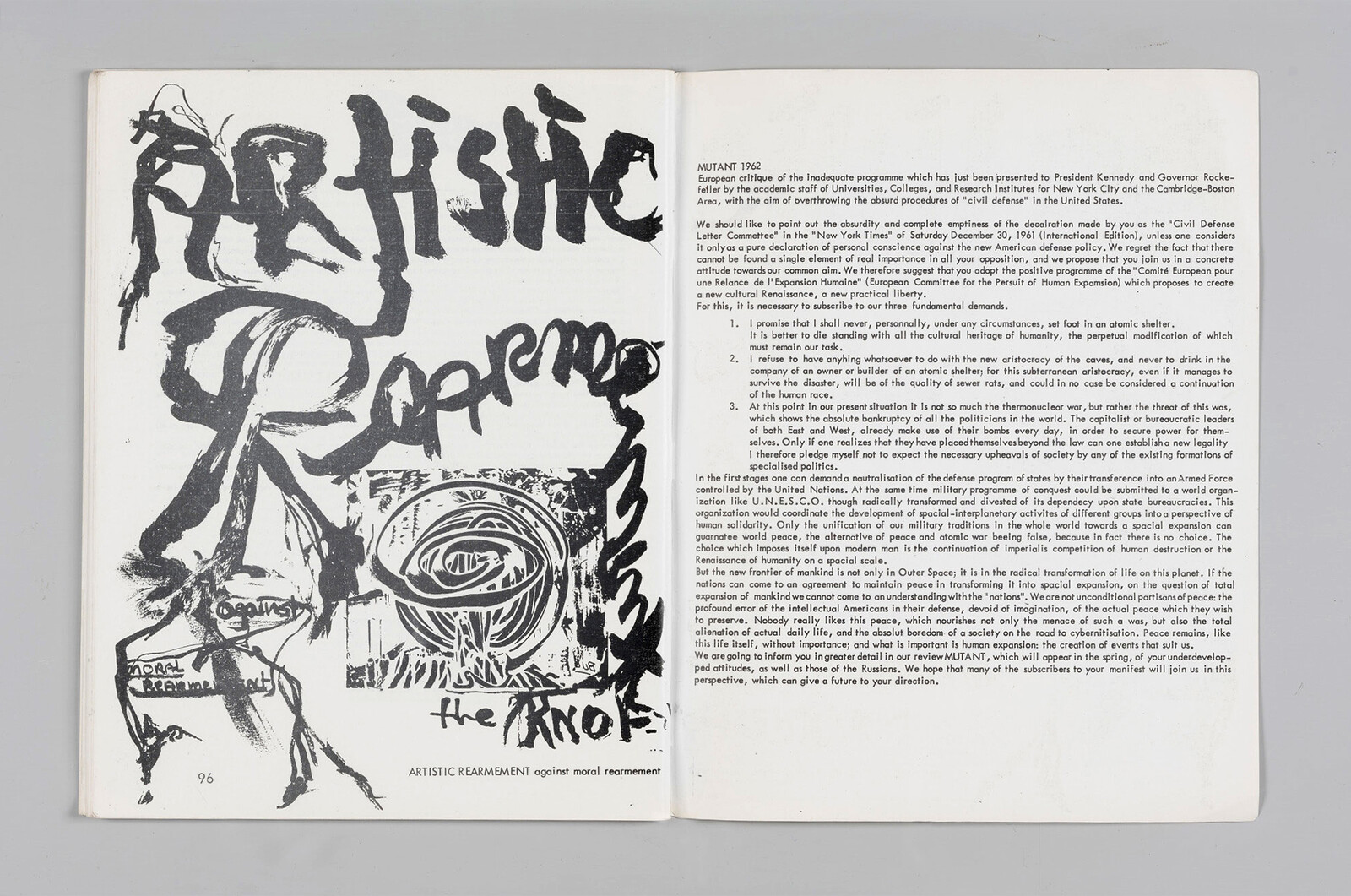

While there are notable exceptions, especially in literature and the cinema, on the whole the art of the “first responders” of the late 1940s and ’50s tended to stage the postwar nuclear age as existential tragedy rather than as a political issue. In his conclusion, Newman asks and asserts: “Shall we artists make the same error as the Greek sculptors and play with an art of overrefinement, an art of quality, of sensibility, of beauty? Let us rather, like the Greek writers, tear the tragedy to shreds.” In much 1950s art, the possibility of a total and remainderless destruction of culture and of life is evoked, yet at the same time symbolically conquered through the proliferation of tattered, ravaged, or starkly simplified and thereby sublime and existential forms. In 1958, during an antinuclear conference in Tokyo, the philosopher and antinuclear activist Günther Anders visited the memorial of the nuclear bombardment in Hiroshima. Its abstract arch, which only appeared symbolic “because the non-functional always suggests symbolism,” reminded him of American abstract expressionism and its endorsement by the US, even by the War Department itself.

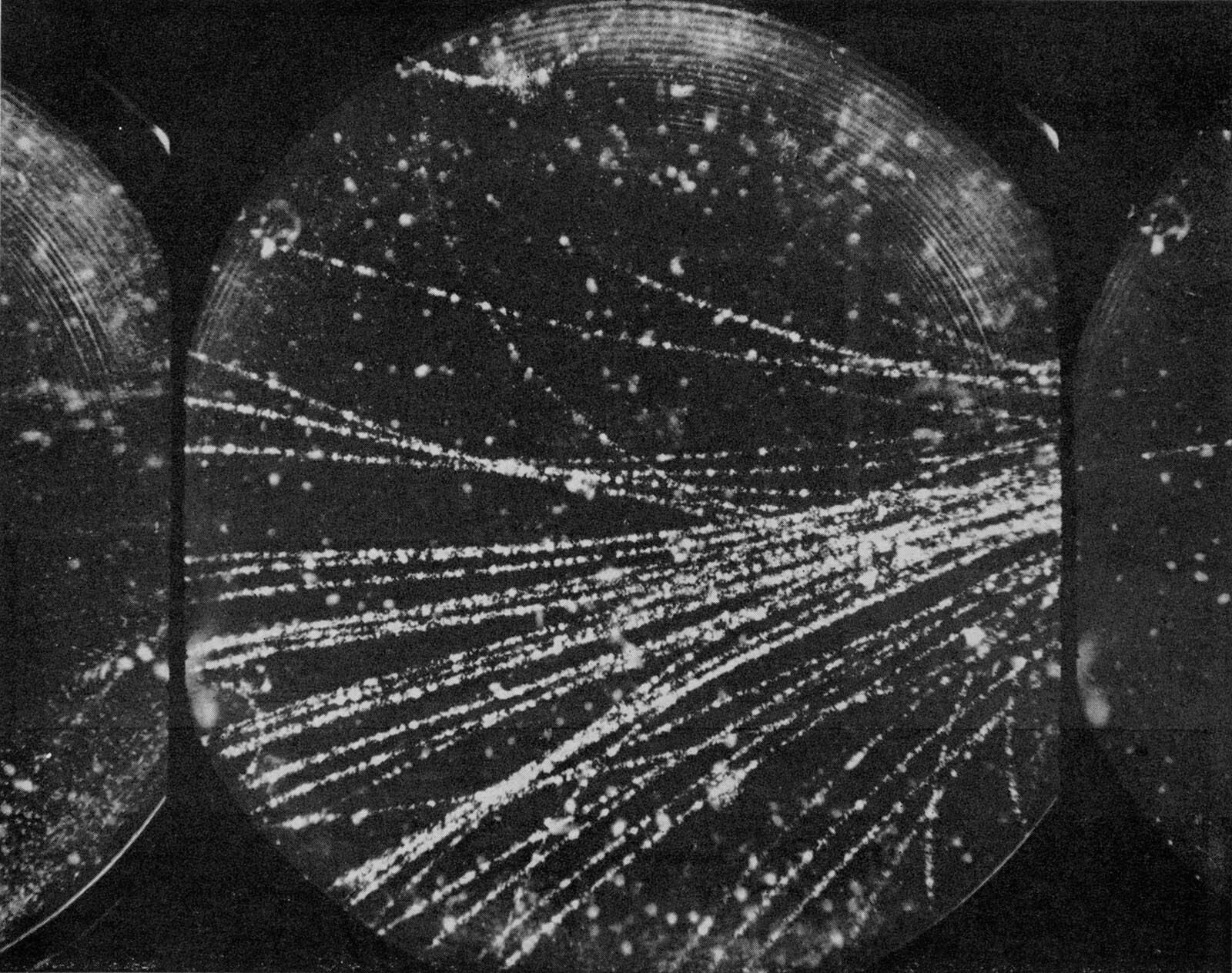

This animation or resuscitation of the gas network wasn’t an outlandish fantasy on the part of the filmmakers. In fact, the plot of Acceleration (1984) was loosely based on the life story of Viktor Glushkov, a pioneering computer scientist tasked with building oil pipeline networks, among other things, after his bold idea of an information network for the USSR was shelved, and his groundbreaking research on socialist artificial intelligence was put on the back burner by authorities. Glushkov was a leading figure in Soviet cybernetic science, a science that he claimed had to be applied to each and every sphere of socialist society. In 1970, top party officials downsized Glushkov’s idea for an overwhelming information-management-and-control network to a series of smaller-scale, disparate network projects. For the better part of the 1970s, he was busy computerizing the Druzhba (Friendship) oil pipeline network that carried Siberian oil into Eastern Europe.