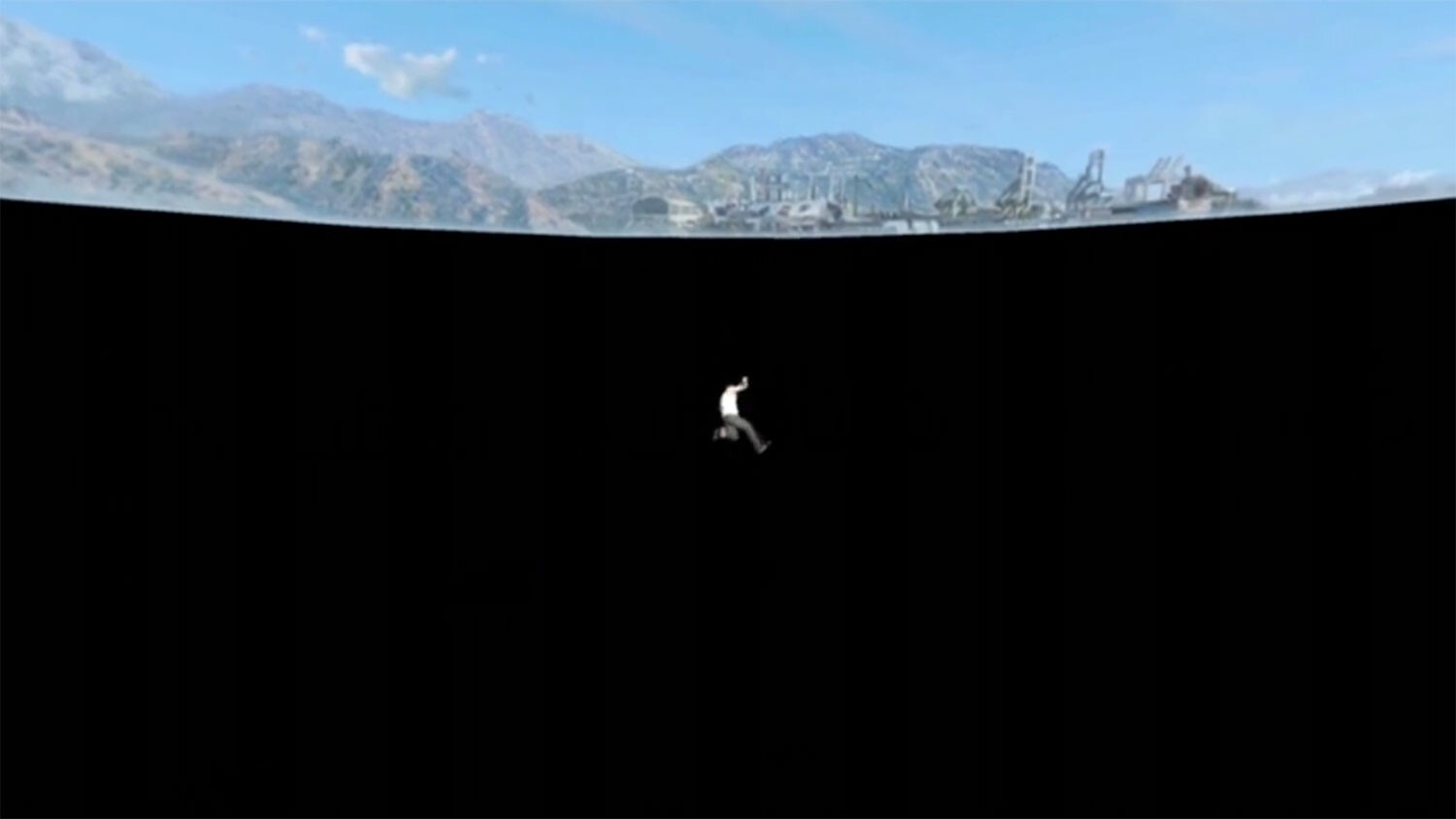

What could a practice of politicizing the image in the twenty-first century look like, considering that navigation—the computational condition of contemporary image-processing—updates, calculates, and incorporates the frame excessively and continuously into the image-making process? In order to render more palpable the beginning of a political ontology of image navigation by means of computation, we should remind ourselves of the principle of twentieth-century montage, which can offer a potent point of departure. Much has been written and produced in the name of montage. In 1967–68, film students, including Harun Farocki, announced the Dsiga Wertow Akademie, an occupation of their film school, the German Film and Television Academy in Berlin, an act that paid tribute to montage as a cine-political practice. Montage was pioneered by Esfir (Esther) Schub and Dziga Vertov, emerging from the world of Soviet cinema during the period of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1918. In other words, montage’s potency to mobilize the image for emancipatory processes was initially built from participation in communist world revolution.

True Fake

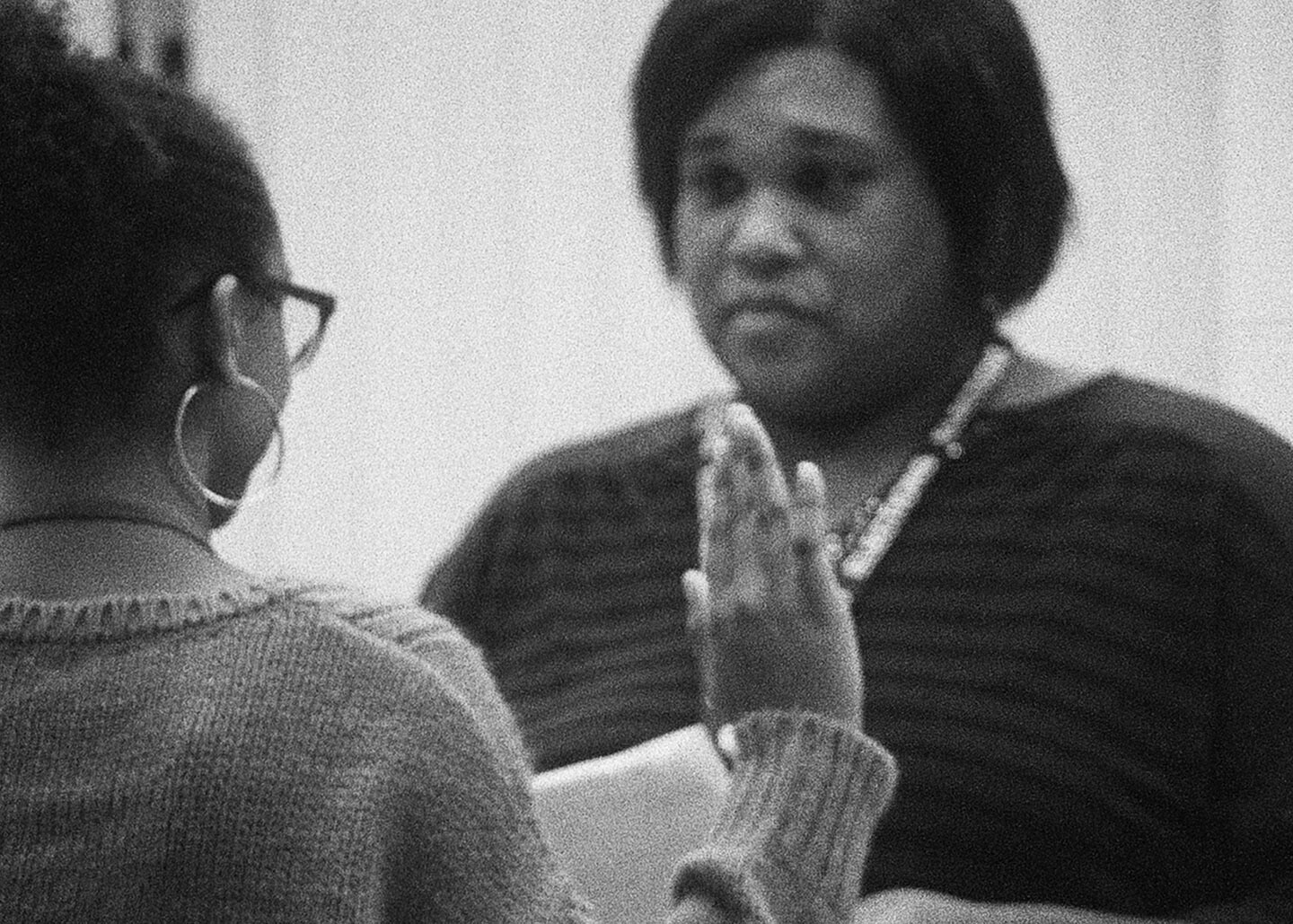

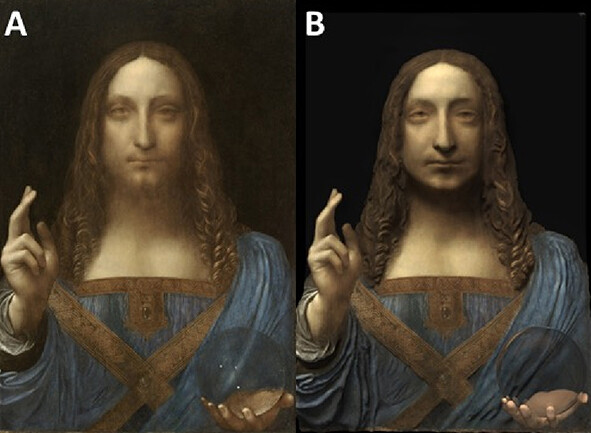

The examination of the unstable and ambiguous relationship between reality and documentary facts is a noticeable tendency in works by contemporary artists. Complementing the screening series True Fake: Artists’ Films Troubling the Real, this reader features critical writings on the epistemological and sociopolitical realness of technological simulations. Discussions on alterations of vision and visibility, as well as asymmetries of perspective and their biopolitical repercussions, highlight blurring boundaries between what at certain times has been known as “fiction” and as “fact,” and alert to the necessity of fathoming new forms of visibility and new public forums.

The question of navigation, which forms the raison d’etre for this conference, is popularly understood as a quotidian practice of movement within computational networks. As a gestural economy compelled by digital interfaces, the habitual activity of navigation tends to recede from critical scrutiny. To begin to comprehend navigation’s historical ontology, phenomenal interfaciality, political imagination, and psychic life requires an effort of defamiliarization that begins by paying attention to this critical inattention.

If Google Earth or a satellite view of the garbage patch proves to be an impossible undertaking, it is because the plastics suspended in oceans are not a thick choking layer of identifiable objects but more a confetti-type array of suspended plastic bits. Locating the garbage patch is on one level bound up with determining what types of plastic objects collect within it and what effects they have. Yet on another level, locating the garbage patch involves monitoring its shifting distribution and extent in the ocean. The garbage patch is not a fixed or singular object, but a society of objects in process. The composition of the garbage patch consists of plastics interacting across organisms and environments. But it also moves and collects in distinct and changing ways due to ocean currents, which are influenced by weather and climate change, as well as the turning of the earth (in the form of the Coriolis effect) and the wind-influenced direction of waves (in the form of Ekman transport). As an oceanic gyre, the garbage patch moves as a sort of weather system, shifting during El Niño events, and changing with storms and other disturbances. Ocean sensing then requires forms of monitoring that work within these fluid and changeable conditions.

Imagined communities are called into being through media, and the reality-based community is no different. Documentary cinema is its privileged means of imagination. Why? With a frequency not found in other forms of nonfiction image-making, documentary reflects on its relationship to truth. And unlike the written word, it partakes of an indexical bond to the real, offering a mediated encounter with physical reality in which a heightened attunement to the actuality of our shared world becomes possible. But precisely for these same reasons, documentary is simultaneously a battleground, a terrain upon which commitments to reality are challenged and interrogated.