Exception

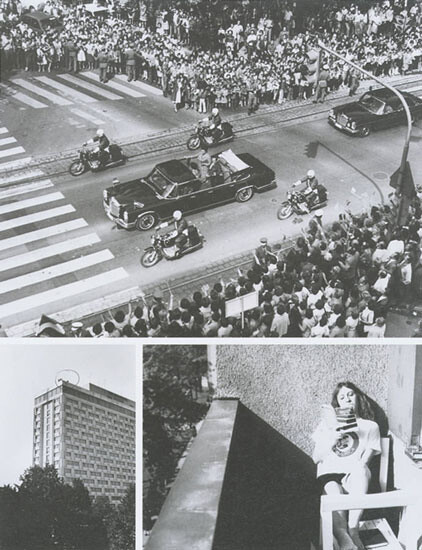

Conventional wisdom dictates that an exception “proves the rule,” but it increasingly

seems that exceptions are the rule. Of course, the previous years of pandemic-driven

isolation, economic shock, and the politicization of personal protection is represented as

one long exception—and to recognize this requires that there is a rule (read: a normal)

to retain. How then do we recognize meaningful social change? How do we recognize a

new normal? Like any compilation, the contents are intended to adhere to a theme, but

inevitably there are departures. The essays collected here include ideas around

interruptions, excuses, evasion, representation/ imitation, and the suspension of

disbelief.

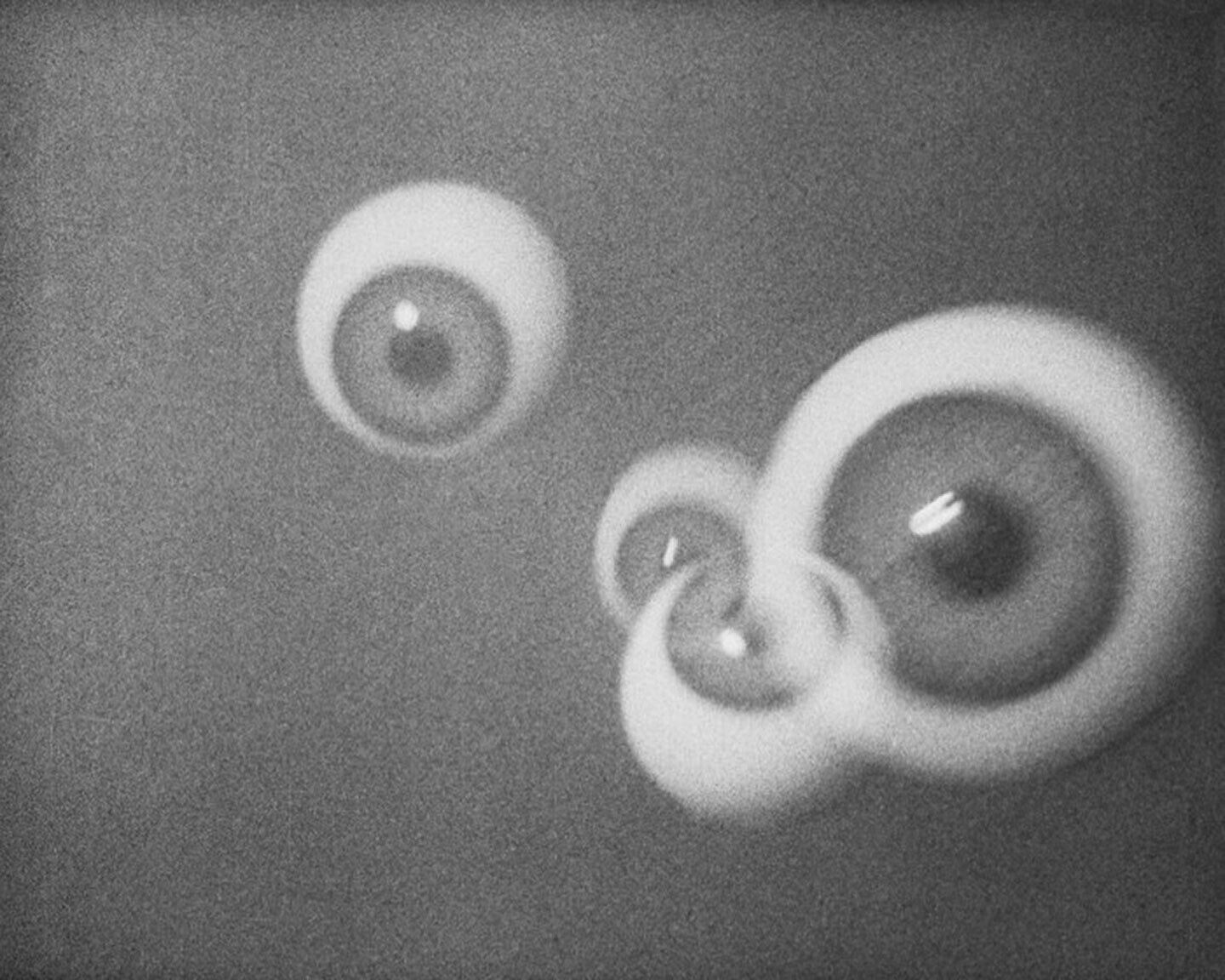

If it is true that the individual is caught in a circle of continuous undulation between enslavement and liberation, trapped in the paradox of simultaneously being her own master and slave, can learning from the logic of the machine provide a path for a new, alien beginning? And if it is true that instrumentality as such has developed its own logic through the evolution of machine complexity, shouldn’t we attempt to think the instrumentality of the post-cybernetic individual beyond the dualities of means and ends?

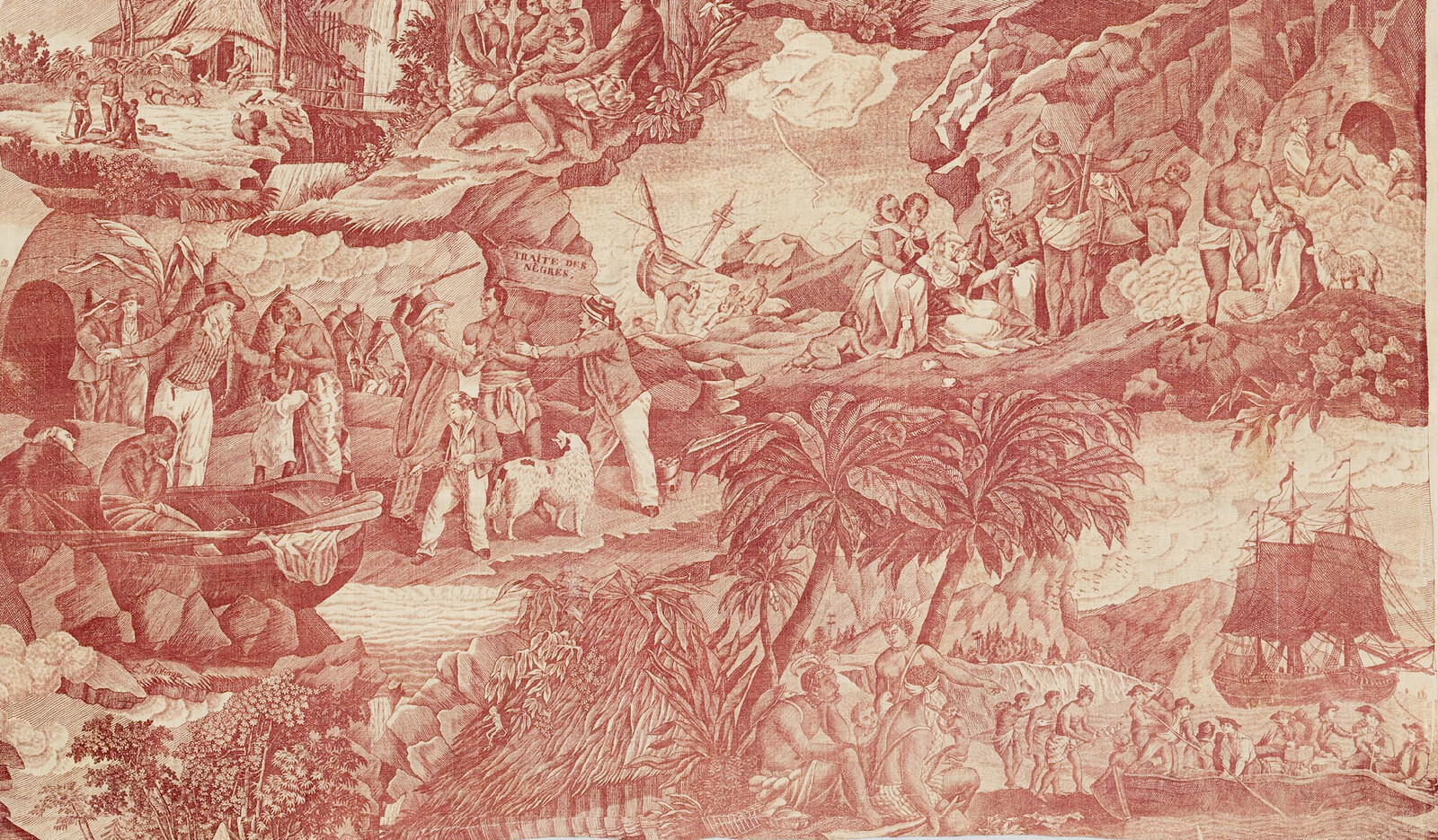

The plantation regime and, later, the colonial regime presented a problem by making race a principle of the exercise of power, a rule of sociability, and a mechanism for training people in behaviors aimed at the growth of economic profitability. Modern ideas of liberty, equality, and democracy are, from this point of view, historically inseparable from the reality of slavery. It was in the Caribbean, specifically on the small island of Barbados, that the reality took shape for the first time before spreading to the English colonies of North America. There, racial domination would survive almost all historical moments: the revolution in the eighteenth century, the Civil War and Reconstruction in the nineteenth, and even the great struggles for civil rights a century later. Revolution carried out in the name of liberty and equality accommodated itself quite well to the practice of slavery and racial segregation.

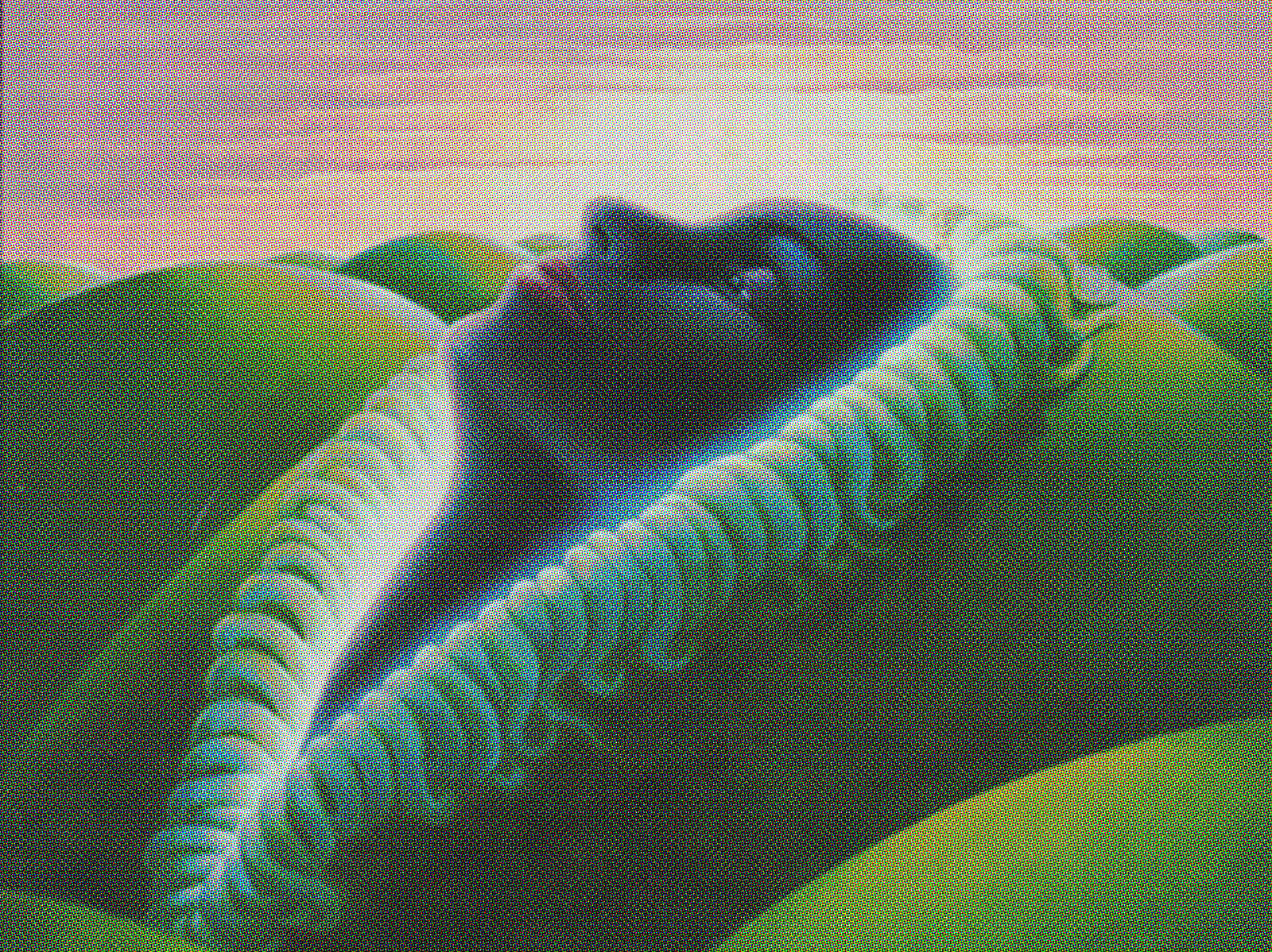

After decades of There Is No Alternative ideology, we see a pathos of the possible that aims to quell fears about empty possibilities without potentiality. But what are the potential possibilities—as opposed to largely hypothetical ones? In Peter Osborne’s characterization, the space of art is project space, and hence the space of the projection of possibilities and the presentation of “practices of anticipation.” And indeed, much contemporary aesthetic practice is possibilist—from speculo-accelerationist “we were promised jetpacks” retro-Prometheanisms to various forms of social and political practice seeking to foster and form alternative forms of assembly and cooperation.