Care

How can care be an interdependent modality? What is the role of ongoing care in these times of crises? Can we orchestrate a collective closeness through systems of care? The etymology of care is derived from the Latin word curare meaning to cure, heal, and curate. So what are the intertwinements of curating and caring? Whether ruminating on viral care and collective care within cultural institutions (iLiana Fokianaki), intimate bodies, healing, and vulnerability (Irmgard Emmelhainz, Zdenka Badovinac) or love and feminism (Maria Lind), to care is to recognize all bonds, between both humans and non-humans; between humans and their systems, their infrastructures and institutions, and to attend to their fragility, carefully.

The Covid-19 pandemic has attacked not only our individual bodies, but our collective body as well. Through thirteen contributions by writers who are mostly from former socialist countries where the space of freedom is contracting once again, this special issue of e-flux journal asks what this collective body actually means, and what it has become.

With the industrial revolution, curing and caring for oneself took an individualist turn: it became a private affair for the privileged. Self-care was turned into a sign of cultural sophistication for the Western imperialist class.

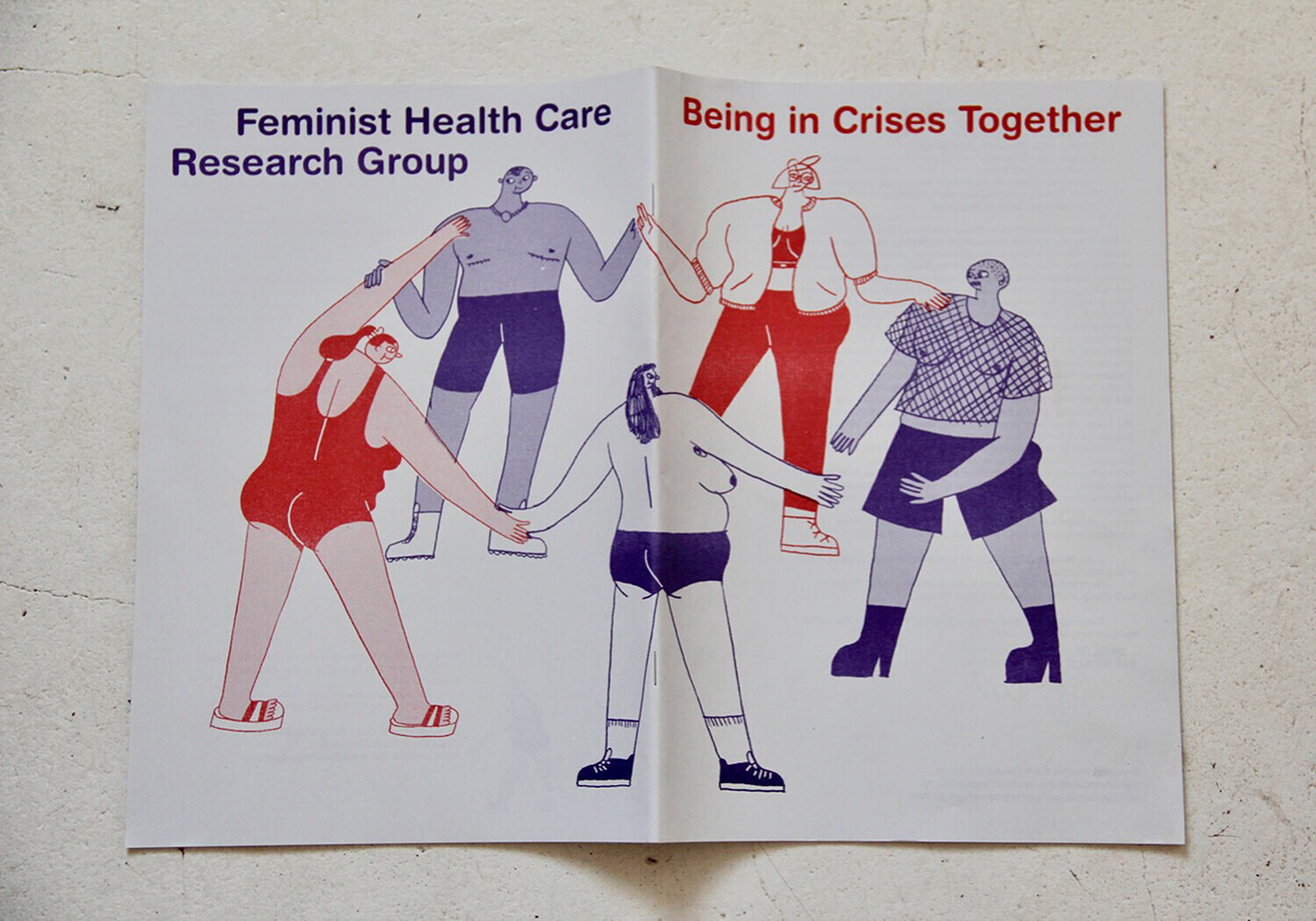

Care and its politics have been a subject of concern to the art world, made all the more urgent by the global pandemic. But is it a real concern that can lead to changes in the way we operate in our institutions and working relationships, or is it merely surface level? How can care, if studied care-fully, provide solutions to the various problems that art institutions and art workers face? How is it that contemporary art institutions are keen—and comfortable—to talk about care when they have been so care-less?

Free love and camaraderie were at the core of Kollontai’s thinking, for her novels and essays describe love as a force that frees one from bourgeois notions of property. As an influential figure, a rare woman in the Bolshevik Party leadership, and commissar for social welfare in their first government, she not only set up free childcare centers and maternity houses, but also pushed through laws and regulations that greatly expanded the rights of women: divorce, abortion, and recognition for children born out of wedlock, for example. She organized women’s congresses that were multiethnic in the way the young Soviet Union practiced controlled inclusion, following Western models. At the time, these were unique measures that were soon overhauled by Stalin, who did not appreciate any attempt at ending what Kollontai called “the universal servitude of woman.”

Mutual love is often thought of as mutual recognition: I see you for who you are and you see me back. But recognition is inevitably also a naming, a fixing, a pinning down. In order to recognize, you have to categorize, and categories are notoriously inflexible. Recognition, if understood as a projection that disallows the evolution of self and identity, becomes restrictive rather than liberating. However inadvertently, the recognition required for mutual love can easily slip into a form of control.

But what does vulnerability actually mean? Is it being able to acknowledge a state of pain or insecurity, embracing the feeling of coming undone? I feel that it’s something I’ve tried to hide from others and from myself. At the cost of headaches, a bloated stomach, the inability to articulate a sentence. A mental-physical feeling of paralysis. I now suspect that people spend a lot of time and effort hiding in this way. Could I overcome my terror of falling apart if I allowed myself to rely on others, on you? Or should I be a “cruel optimist” and create hopeful and positive attachments, in full awareness that they will not work out?