Gamification

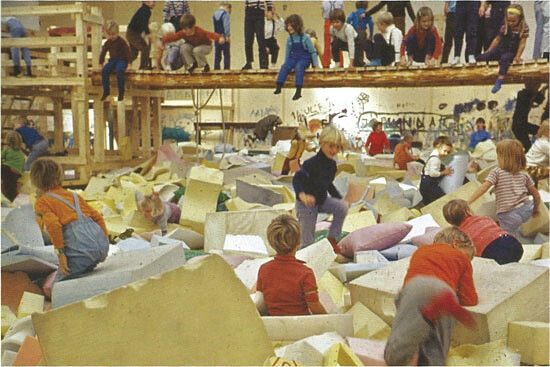

Children’s games’ disappearance in the public sphere urges the experience of the unheard-of or the unthinkable and reveals a politics for undoing that orientates to the future of un-apprehended necessity. Art intersects with games in the political struggle against capital’s colonization of the future and humanity’s terrorizing extinctionfrom planetary collapse. Freedom’s social limit is perceived in play’s aesthetic experience which responds to reality’s mimetic relations. The political inability tosolveaesthetic problems in the social sphere and vice versa is compared to a game and life’s meaning. Utopia’s telos is an elusive, repressed game of historical, logical, dialectical orders.

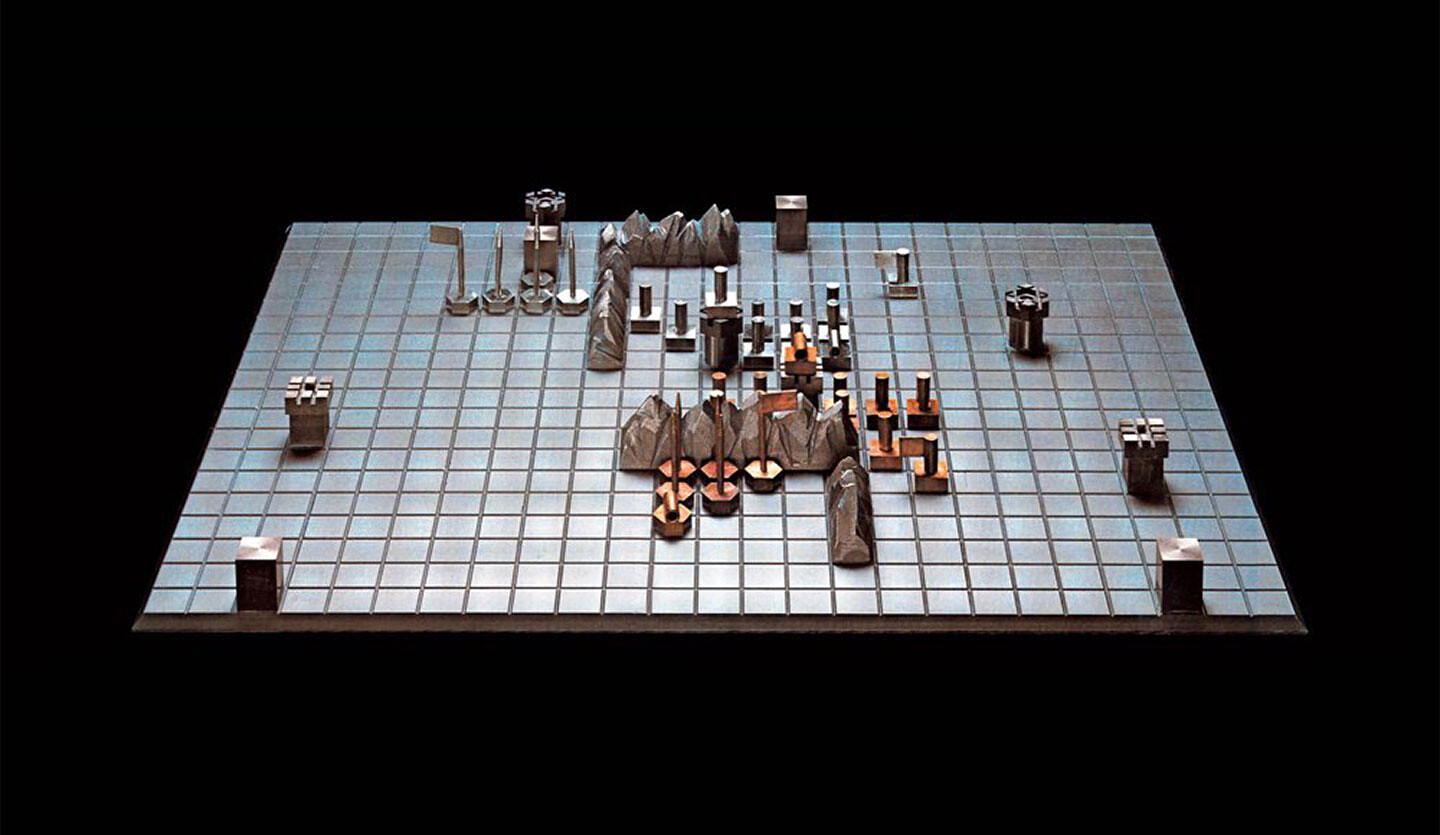

I had seen the banner before; it was made by the former dean of the School of Military Design at Pratt. The SMD dates back to World War II when the institute, rising to meet the moment, ran an Industrial Camouflage Program and recruited students on campus. Five alumni of the time, including Ellsworth Kelly, became known for their service in the “Ghost Army,” a unit that employed creative tactics—inflatable tanks, phony radio transmissions, even fake generals—to deceive German forces. Pratt leveraged their success and built lasting ties with the military, creating a new model of art school.

What is life in a world where I am also the architecture of that world? Until recently, the history of Western scientific development has been a history of a brutal spiritualism, where discoveries of cosmic mechanics only further displace the human observer. I might gain access to God’s computer in a quest to commune with higher forces, only to progressively discover that material forces are programmed as an inhospitable abyss in which my life means nothing. Science might come to the rescue to draw these material forces back under human command, weaponizing and industrializing their power to limit their threat. From Descartes conceding that we possess an exceptional soul in spite of being animate machines and Darwin’s allowing us an aristocratic status in spite of being animals, a brutal self-extinction has haunted (perhaps even guided) the European spiritual imaginary since the Enlightenment. We might eventually consider that mechanical forces and animal survival might have better things to do than conspire to exterminate our human kingdom the moment we observe them. In the meantime, we still need to contend with a world or worlds that serve our every need in the absolute, even amplifying them into architecture, sealing us in and serving us at the same time.

There is a flagrant imbalance between the war machines of Capital and the new fascisms on the one hand, and the multiform struggles against the world-system of new capitalism on the other. It is a political imbalance but also an intellectual one. Our first thesis is that war, money, and the State are constitutive or constituent forces, in other words the ontological forces of capitalism. The critique of political economy is insufficient to the extent that the economy does not replace war but continues it by other means, ones that go necessarily through the State: monetary regulation and the legitimate monopoly on force for internal and external wars. To produce the genealogy of capitalism and reconstruct its “development,” we must always engage and articulate together the critique of political economy, critique of war, and critique of the State.

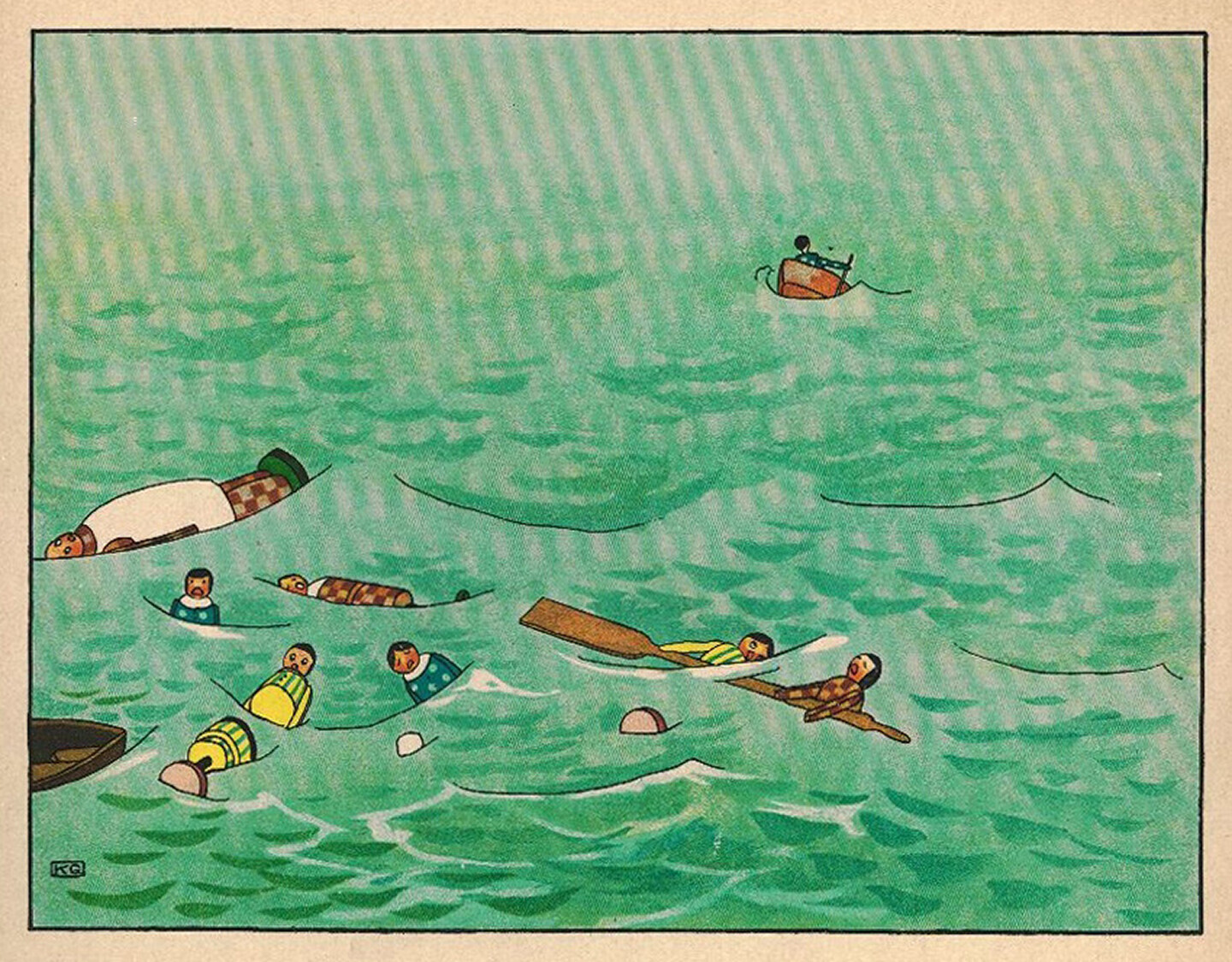

My taxonomy of images of alterity from the twentieth century—ethnographic, militant, and witness—is not opposed but rather transversal to Rancière’s. What I am interested in, firstly, is tracking the kinds of discourses underlying images of Western alterity in the aftermath of the postcolonial critique of the ethnographic image, the demise of the third-worldist militant image, and the exposure of the limitations of the witness image, which often serves to perpetuate the figure of the “victim.” These visibilities have perhaps become the “visual” in Daney’s sense. Second, I wish to consider the possibility of an image of soulèvement—in the sense of an image of an other that could threaten Western imperialism and capitalist absolutism, a system this is consensually driven by the desire and need for visibility, and that legitimates social Darwinism with racism and misogynist speech in the public sphere.

Forty years ago, I remember shouting, “No future! No future!” with some young British musicians. I thought it was the provocation of an unlikely avant-garde. Now, everybody thinks that the future is over; now, the sentiment aligns with a conformist position held by most of humankind. “No future” has become common sense, and this is why cynicism is expanding in contemporary culture, in contemporary political behavior. Futurism was the expression of a society that expected something from the future, and of a society that truly felt the warmth of community, whether encapsulated in the nation, the family, or social ties to working communities. All the above was the reality of lived experience a hundred years ago. No more! Today, the nation is a nonexistent thing. The dissolution of the nation is an effect of the pervasive digitalization of information and of power based on information. Do you think that Google belongs to the United States? Not at all. The United States belongs to the territory of Google. So does Italy, and France, and so on.