Dizziness

My body felt spongy and disoriented. I no longer had a sense of the size of the room or where

anyone was within it, I didn’t know where the walls were, or the distance between my elbow

and hip, my chin and the floor. I gave myself over to this dizzying absence of location.

—Karen Sherman, “The Glory Hole”

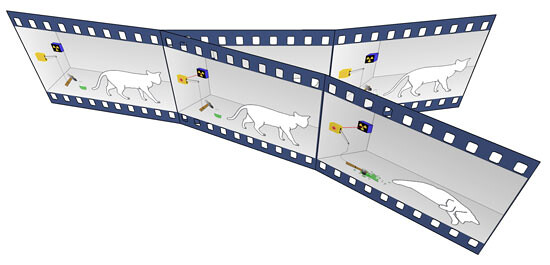

Dizziness: a feeling of disorientation, a loss of balance, or our capacity to “navigate the unknown.” Ruth Anderwald, Karoline Feyertag and Leonhard Grond argue that “dizziness, marked by an increasing feeling of loss of control and vulnerability, is a midway state at the point where everything and nothing seems possible, where certainty and uncertainty are in superposition.” In Dizziness—A Resource, the editors turn to the potential reading of dizziness as method; as a generative means to shake “normative assumptions and perceptions,” as well as unsettle dominant modes of knowledge production and orientation.

The popularity of the phrase “new normal” amongst news readers implies a drastic shift in lifestyle and reality. However, as Helen Lewis writes, the global pandemic, in fact, exposes preexisting inequalities within society—for example, the unevenly distributed death rates, the invisibility of care workers suggested by lack of PPE, and the gendered responsibility over childcare. For Anderwald, Feyertag, and Grond, dizziness thus effectively proposes a catalyst for change: it unbalances societal monolithic certainties, and enables impermanence, re-orientation, and “con-fusion.”

At first, I thought “performative” was coined by dance people in order to sound like museum people. But then I realized that the art world’s misuse of this term predates the dance world’s. Which made way more sense but also bummed me out even further. Why would dancemakers do this to ourselves? Why would we let museums rename what it is we already do? And why would we ourselves then use that language to describe what we have already been doing all these years? I long to see the dance world assert its language as part of its commodity. If you want to present dance, you need to know how to talk in dance’s existing language. It serves the form just fine because it is of the form. Dance doesn’t want to talk about itself from the remove of class or body. Dance wants to be hot in the center of its own glory hole—though it will happily pee on the museum steps for the right price.

She couldn’t move, and this quickly distorted every perspective, collapsing the vanishing points. She transmitted her instability to the surroundings, a fluctuation that made it impossible for her to grab on to something. To grab on to anything. All her memories had dissolved into that uncontrollable fluctuation. This was why she took Remembrant, so she could see them scroll by as though on a roll of celluloid. She knew they were hers, those memories, but she didn’t recognize them. Her memories from ten years earlier when she threw her arms around her mother’s neck, and her memories from two nights ago—which she felt in her muscles and tendons, but didn’t recognize—when she had come across the two old corpses, like buoys tossed around by a stormy sea, by a storm which had its origin in herself. She had bludgeoned them repeatedly in order to finally attain a bit of calm.

Does climate change instantiate the “Kantian gap” between phenomenon and thing-in-itself, or rather actualize the Kantian correlation between mind and world, of which the thing-in-itself is the irrelevant remainder? As Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro have argued, “We can see the irony of our predicament as that of a catastrophic terrestrial objectivation of the correlation”—in other words, “human thought, materialized as a giant technological machine of planetary impact, effectively and destructively correlates the world.” If the productive abstractions of modern technoscience—this weaponized, transformative, operative logos—have remade the world, they have done so through the “actually existing linearity” of GDPs and CO2 levels.