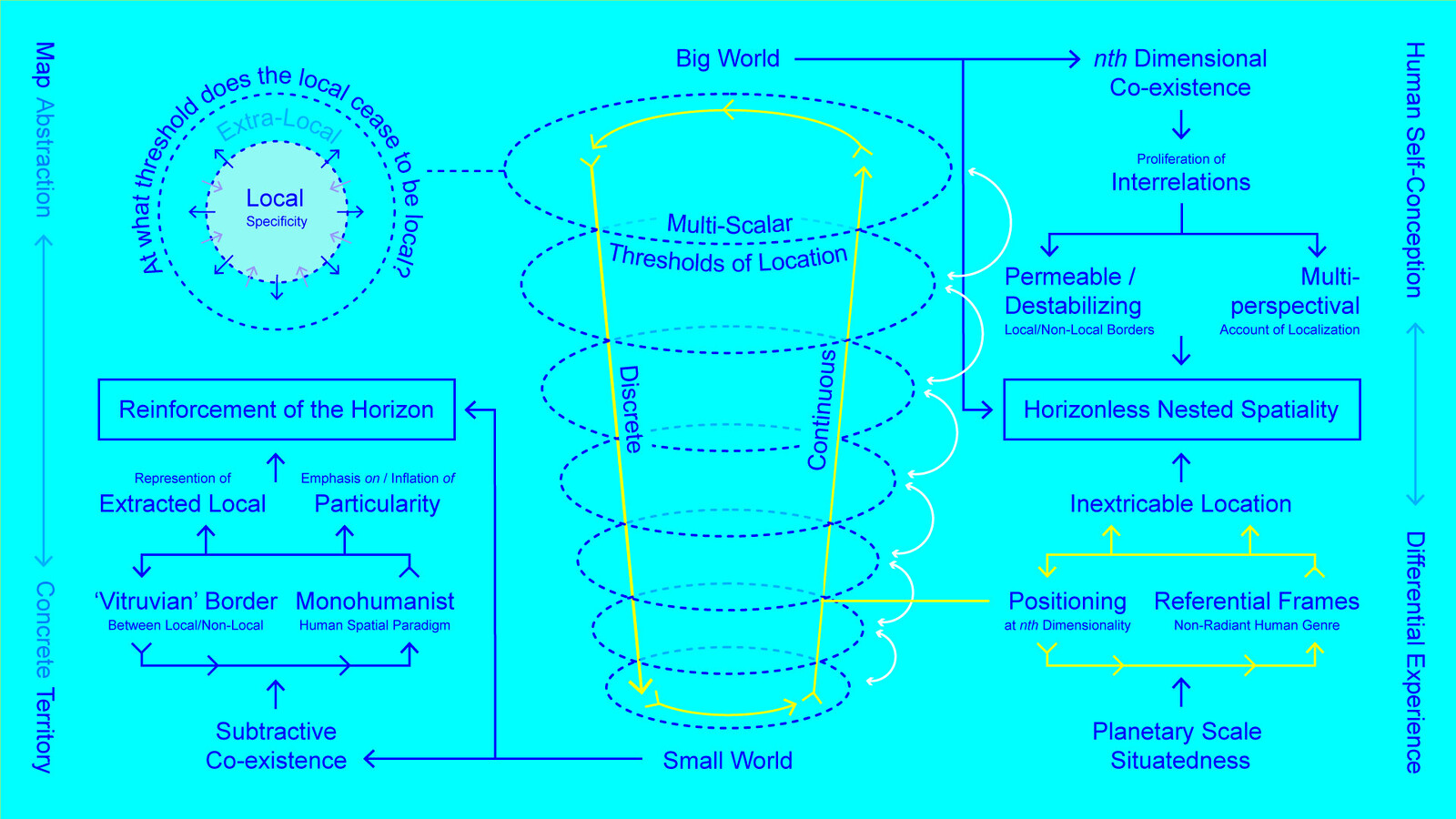

There are those who champion, or who actively seek to amplify, the navigational turbulence produced by this decentered human position at the planetary scale, making for an urgent battle over claims on orientation. Such tendencies thrive among several techno-neoreactionaries, who, in denying absolutely any form of planetary navigability from a resituated human position, ultimately advocate for the stripping of humanity’s cognitive-political agencies to transform given frames of reference. Paradoxically, what is often perceived as a form of techno-fetishist futurism is nothing but an unimaginative conservatism that celebrates the preservation of existing frames of reference. These existing frames are defended as if they are an immutable fact of nature, a world “naturally” oriented by nineteenth-century navigational frameworks, now augmented by twenty-first-century AI, smart cities, and iPhones. Implicit endorsements for dehumanization can be found in this destructive negation of these capacities. At this juncture, it becomes evident that the struggle for orientation at nth-dimensionality coexistence demands intervention on this artificial plane, in order to dislodge naturalized conservatisms that are often disguised as blinking futurity.

Togetherness

How to be together otherwise? This recurrent question hints at some of the complex ambiguities that different forms of being-with and becoming-with epitomize. Togetherness, as a shared sense of belonging, has become a contested term indicating extremes and in-betweens of agency and subordination, of exclusion and inclusion, of death and survival. For some, togetherness may imply an element of physical warmth which differentiates it from a similar word: connectivity. Realities-in-common today tend to require, more than anything else, a shared software. Such an infrastructure is oftentimes coded by homophilic algorithms erasing traces of social difference and cultivating purified relations. Hence, the very search for novel modes of communality, of more livable futures for both humans and non-humans, continues to be crucial for the continuity of our many worlds.

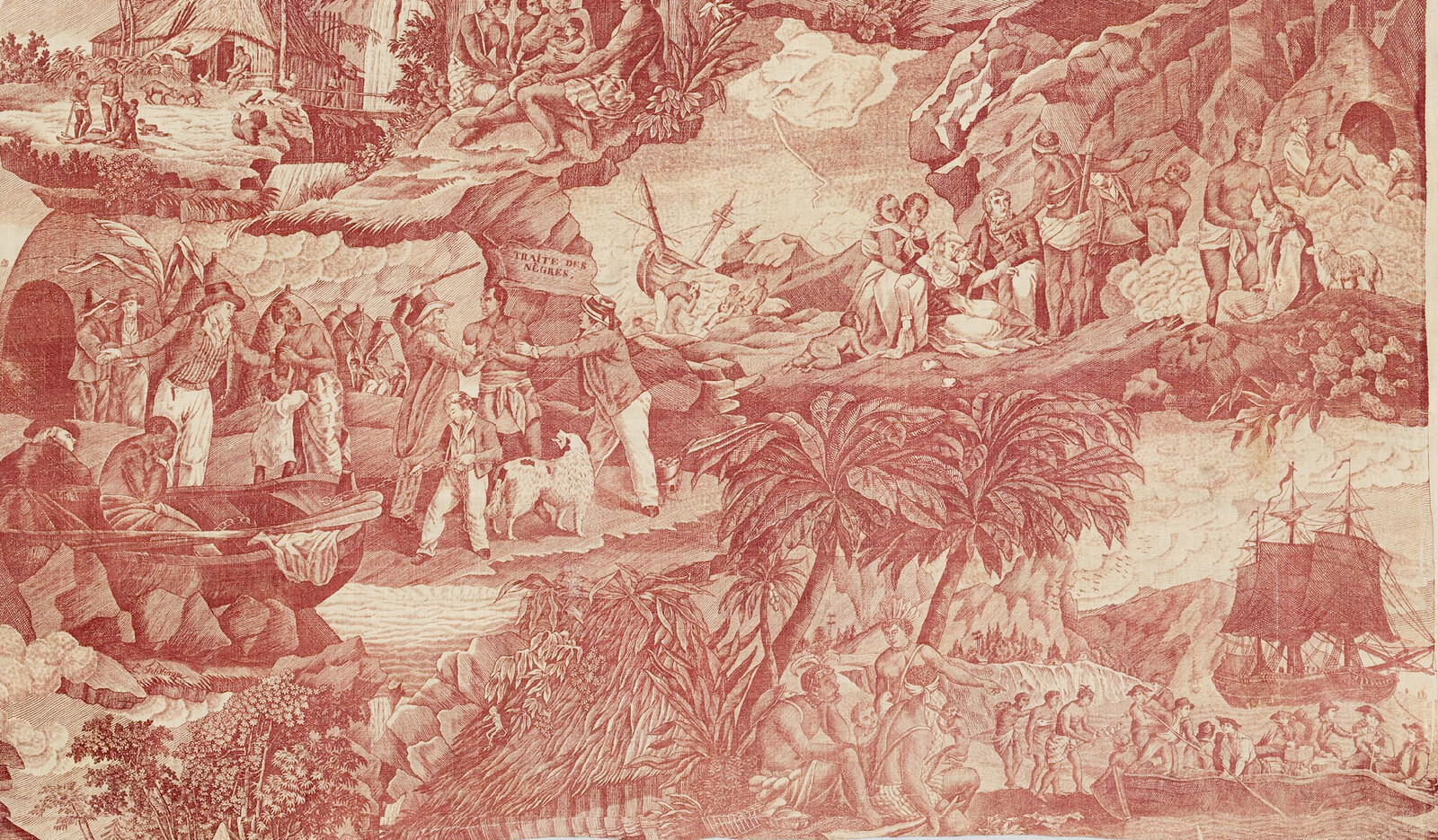

The plantation regime and, later, the colonial regime presented a problem by making race a principle of the exercise of power, a rule of sociability, and a mechanism for training people in behaviors aimed at the growth of economic profitability. Modern ideas of liberty, equality, and democracy are, from this point of view, historically inseparable from the reality of slavery. It was in the Caribbean, specifically on the small island of Barbados, that the reality took shape for the first time before spreading to the English colonies of North America. There, racial domination would survive almost all historical moments: the revolution in the eighteenth century, the Civil War and Reconstruction in the nineteenth, and even the great struggles for civil rights a century later. Revolution carried out in the name of liberty and equality accommodated itself quite well to the practice of slavery and racial segregation.

In our neoliberal era, subjectivities are being further shattered by absolute capitalism and its crisis of human, environmental, and interpersonal relations manifested, for instance, in femicide; or in the transformation of the mechanisms of love (feelings, emotions, seduction, desire) into commodities. Brokenness also stems from capitalist “productivity,” which means dispossessing peoples not only of their territories, but also their labor, bodies, language, lives. These forms of violence have been justified by the production of an abundance of goods, so that a portion of the global population can have anything we want, so we can live “good” lives designed by technocracy, adorned by culture, so we no longer have to make a living with the sweat of our brows. As the communist idea of cooperation is obsolete, excess production and labor achieved through violence and dispossession provide the general feeling that we can have comfort while being relieved of the pressure of contributing to society and of the feeling that we are needed by others.

Through its aesthetic liberation of things, ideas, and layers of time, art constructs imaginaries of interdependence, which in their own way contribute to a society of solidarity. Today, during this time of pandemic, we like to talk about us all being in the same boat, a metaphor that has replaced the catastrophic image of overcrowded boats of refugees crossing the Mediterranean. But the most powerful metaphor of the present time is the metaphor of the virus, which represents how everything influences everyone. But this is only our view of viruses, our exploitation of its properties. What viruses themselves think about this, nobody knows.

It is particularly dangerous when something from the cultural imagination is later read as a reliable prophecy, since it renders the abstraction and alienation of human suffering as a set of perpetuating clichés. For example, the only similarity between the current pandemic and the “predictions” pulled from Dean Koontz’s 1981 novel The Eyes of Darkness, noted on social media this February, is a reference to a killer virus called “Wuhan-400” that emerged from the Chinese city of Wuhan. As the reality of the pandemic unfolds globally, “China” continues to operate as a spectacle in both intellectual gossip and pop-cultural speculation. But we need more than just an arbitrary imagination of the suffering. There is rage, confusion, fear, and despair: concrete and real.

WEB.jpg,1600)