If we begin with the understanding that police protect property and their owners, we can expect this to be its primary consequence: those who have very little property in a community are bound to experience a frequency of bad encounters with law enforcement that is much higher than those who have a lot of property. And so it is. What we find in the US, the world’s top ownership society for the past hundred years, is a vast jail, prison, and parole system filled with men and women who do not own much of anything. From this fact, which links poverty to the business of policing, we also find an explanation for the overrepresentation of black Americans (who make up about 13 percent of the general population) in the US’s state prisons (they make up 40 percent of the penal population).

Loot and Looting

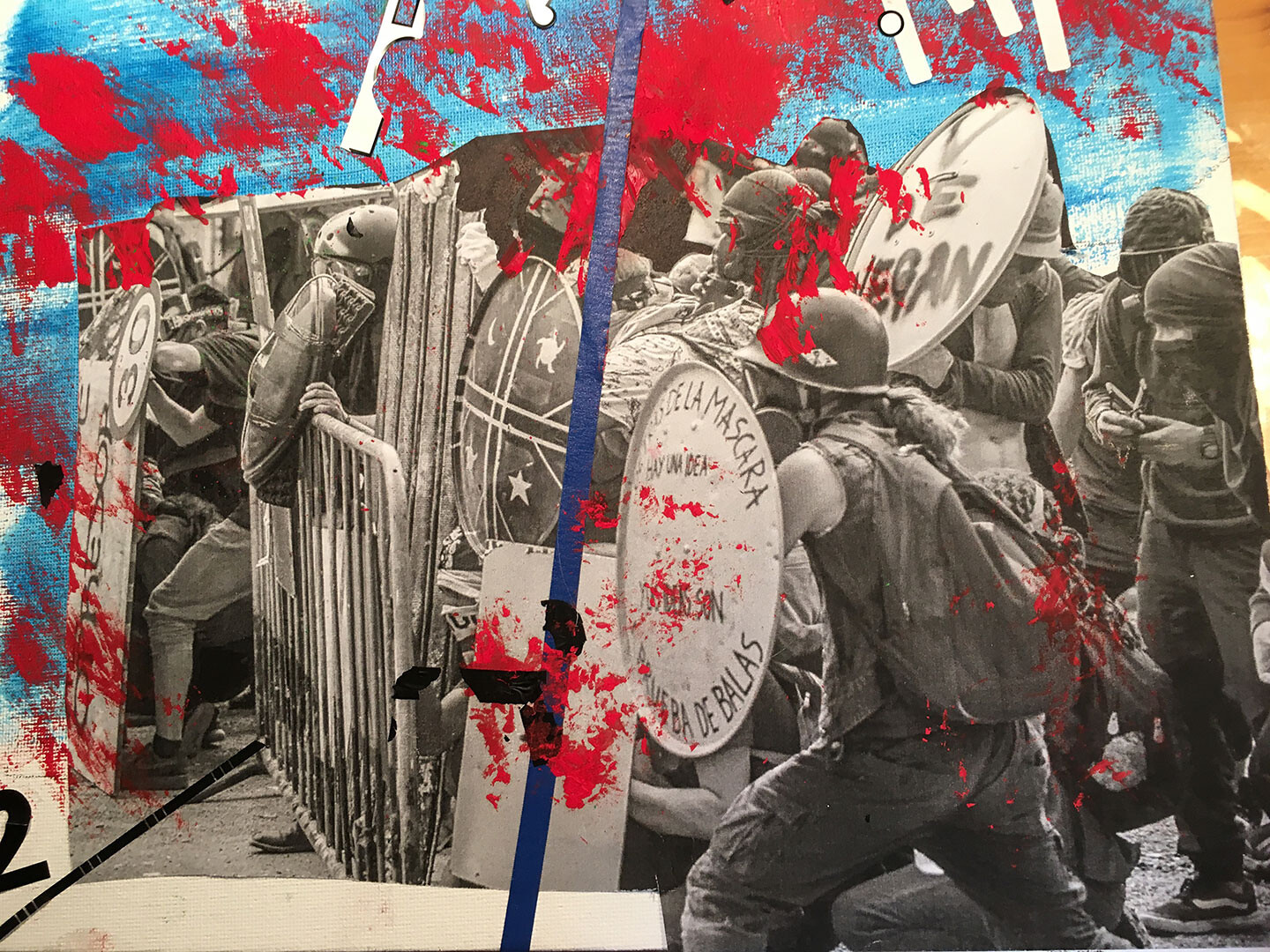

In Stealing Beauty (2007), Guy Ben-Ner writes: “Children of the world, unite. Release the future from the shackles of the past. My peers, it is our time to steal. Not in order to gain property but in order to lose respect for it.” Widespread protests and insurrections across the globe have given new urgency to conversations concerning property, possession, and looting. From a television in a Best Buy to a tank on a pedestal, the political meanings of loot and looting change with object, actor, and context. This reader moves between the street and the institution, following the actions of individuals, the masses, and the state. It considers the inherent tensions within the museum: working hard to circulate duty-free art, to guard national loot, and to develop convincing and inclusive postcolonial narratives. As museums seek to reflect the lives and struggles of marginalized populations, does looting take on a new guise? What role will museums and galleries play in providing counter-narratives to fascist rhetoric and policies? And can we imagine a museum divested from collections, commodity, and property?

Artists in Iraq, particularly young artists who came of age during the invasion, have never lacked the desire or ability to create art. But globally visible contemporary art, as anyone in the field knows, often assumes a ladder of prestigious art-school attendance, production support, mentorship, residencies, international travel, and social skill, usually in English. At Iraq’s two main art schools in Baghdad, which are free of cost, middle- and working-class students hardly have access to resources reserved for elites. Instead of journalists speculating what Iraqi art could have looked like—or curators failing to engage with artists outside their comfort class—it would be more useful to consider how actually-existing forms of production could be supported and understood. Young Iraqi artists never stopped working, and are informed—formally and informally—by the extensive visual and political histories that stretch from the Sumerian era to Baghdad’s current sprawling metropolis. Which “Iraq” is ultimately being recuperated in “Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011”?

Thanks to his ignorance and moral abjection, Donald Trump represents the true soul of America, the unmovable soul of a population formed by a never-ending sequence of exploitation, oppression, bullying, invasions, and abominable crimes. Nothing but this. There isn’t an alternative America, as many thought in the 1960s and ’70s. There are millions of women and men, mostly nonwhite, who have suffered from American violence, and especially at a certain point in the ’60s and ’70s, fought to reform America to become more human. They failed, because there is no way to reform a nation of bigots and killers.

Imagine experts in the world of art admitting that the entire project of artistic salvation to which they pledged allegiance is insane and that it could not have existed without exercising various forms of violence, attributing spectacular prices to pieces that should not have been acquired in the first place. Imagine that all those experts recognize that the knowledge and skills to create objects the museum violently rendered rare and valuable are not extinct. For these objects to preserve their market value, those people who inherited the knowledge and skills to continue to create them had to be denied the time and conditions to engage in building their world. Imagine museum directors and chief curators taken by a belated awakening—similar to the one that is sometimes experienced by soldiers—on the meaning of the violence they exercise under the guise of the benign and admitting the extent to which their profession is constitutive of differential violence.