In our neoliberal era, subjectivities are being further shattered by absolute capitalism and its crisis of human, environmental, and interpersonal relations manifested, for instance, in femicide; or in the transformation of the mechanisms of love (feelings, emotions, seduction, desire) into commodities. Brokenness also stems from capitalist “productivity,” which means dispossessing peoples not only of their territories, but also their labor, bodies, language, lives. These forms of violence have been justified by the production of an abundance of goods, so that a portion of the global population can have anything we want, so we can live “good” lives designed by technocracy, adorned by culture, so we no longer have to make a living with the sweat of our brows. As the communist idea of cooperation is obsolete, excess production and labor achieved through violence and dispossession provide the general feeling that we can have comfort while being relieved of the pressure of contributing to society and of the feeling that we are needed by others.

Love

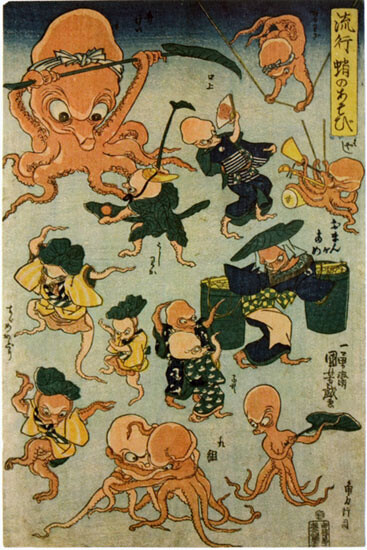

Love survives, love thrives, whether in radically decentred, sensual bodies (Chus Martínez, “The Octopus in Love”); impossibly countering histories of violence (Irmgard Emmelhainz, “Decolonial Love”), or reconfiguring emotional and bodily hierarchies (Maria Lind,“Soon”). Can love be measured, quantified under capitalism (Kuan Wood, “Is it Love?”) or confined by contractual terms (Žižek, “Hegel on Marriage”)? Were slow technologies better suited to love (Lee Mackinnon, “Love Machines … ”; Virginia Solomon, “What is Love?: Queer Subcultures and the Political Present”). It is recommended that, against all odds, you finish your Love reading with a sweet last word carrying “a high love quotient” (Arthur Jafa and Tina M. Campt, “Love is the Message … ”)

Free love and camaraderie were at the core of Kollontai’s thinking, for her novels and essays describe love as a force that frees one from bourgeois notions of property. As an influential figure, a rare woman in the Bolshevik Party leadership, and commissar for social welfare in their first government, she not only set up free childcare centers and maternity houses, but also pushed through laws and regulations that greatly expanded the rights of women: divorce, abortion, and recognition for children born out of wedlock, for example. She organized women’s congresses that were multiethnic in the way the young Soviet Union practiced controlled inclusion, following Western models. At the time, these were unique measures that were soon overhauled by Stalin, who did not appreciate any attempt at ending what Kollontai called “the universal servitude of woman.”

It’s one of the reasons I’m not generally interested in making films about white folks. I’m really interested in making work that is always foregrounding black people’s humanity, bad guys or good guys. I like the alien. I’m a big fan of the alien. I’m a big fan of Hannibal Lecter, who I think is black and passing. Fundamentally, I just want to see black people who are complex. And competent at what they do, even if they’re mad geniuses or whatever.

WEB.jpg,1600)