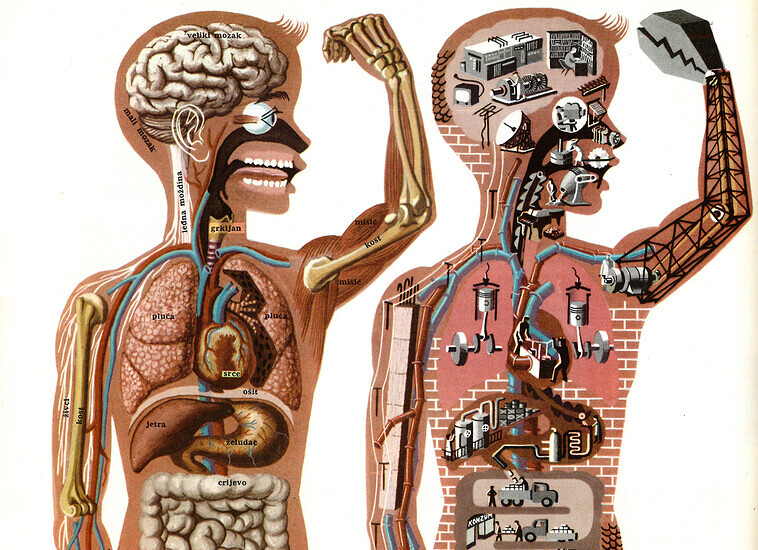

Nothing makes more sense today than to revamp the social imaginary of our collective body. That body is in danger. It is under attack by other species. It is wounded. Its immunity has to be built. It has to be taken care of. It should heal. And it can only heal collectively. At the same time, nothing seems less probable.

Collectivism

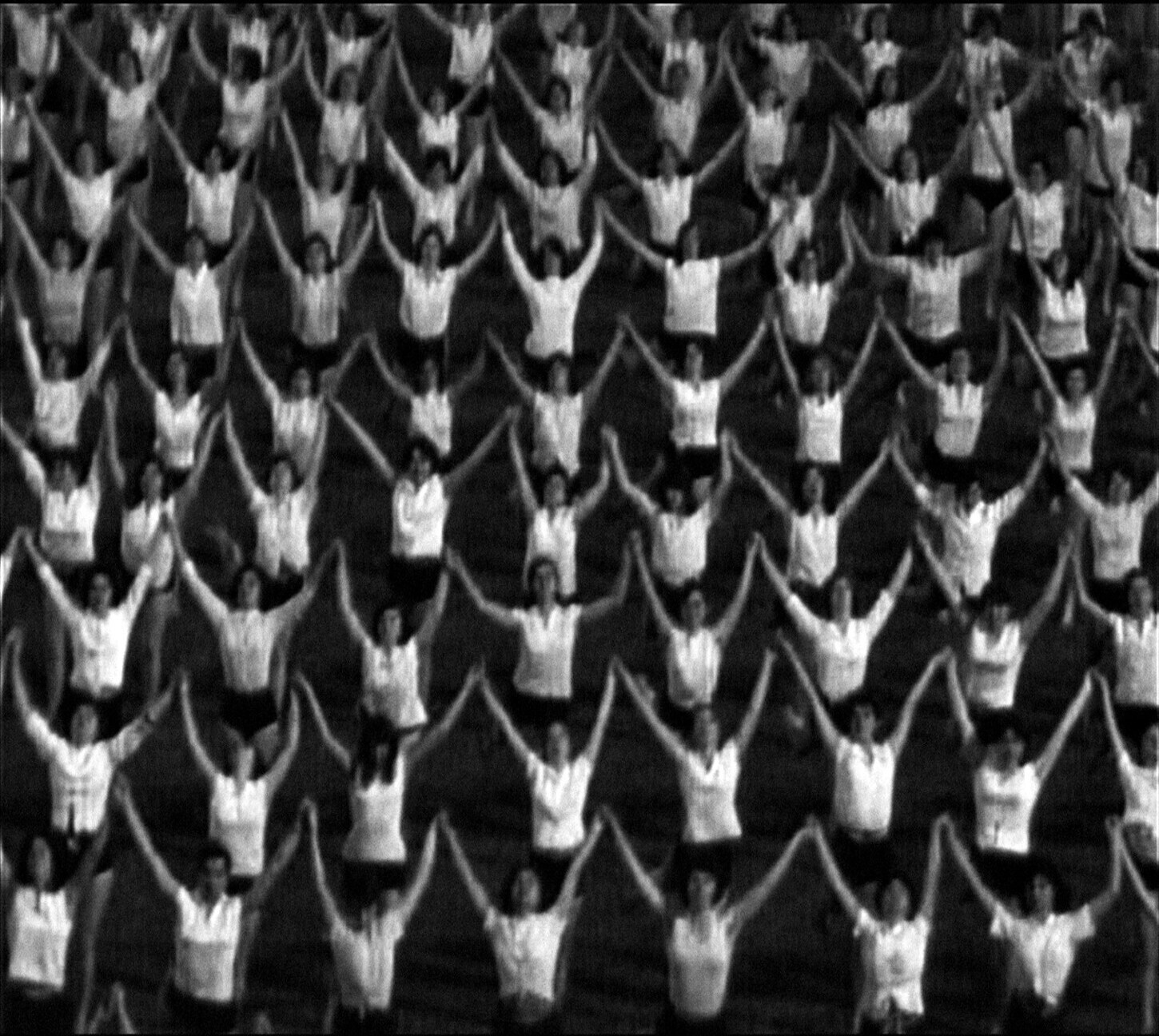

Prior to the Covid pandemic, when the fragmented world shifts towards an age of collectivism, individualism dominated Western culture, proliferating the global market. The unified experience of social estrangement and communal loss of time with family and friends brought about intense longing for proximity to people and the desire to experience oneself in community. An emphasis on the populace at large dominates the news headlines identifying infection rates, death tolls, war casualties, and employment vacancies. Following the murder of George Floyd, tens of millions of people came together to move their bodies in the power of the crowd to command change and attempt to topple racist institutions. The infrastructure for change exists within the power of collective action. Being in unison can feel empowering, liberating, and intoxicating. Dissolving one’s personal identity into the collective can be the first step toward garnering trust in something greater, otherwise known as hope.

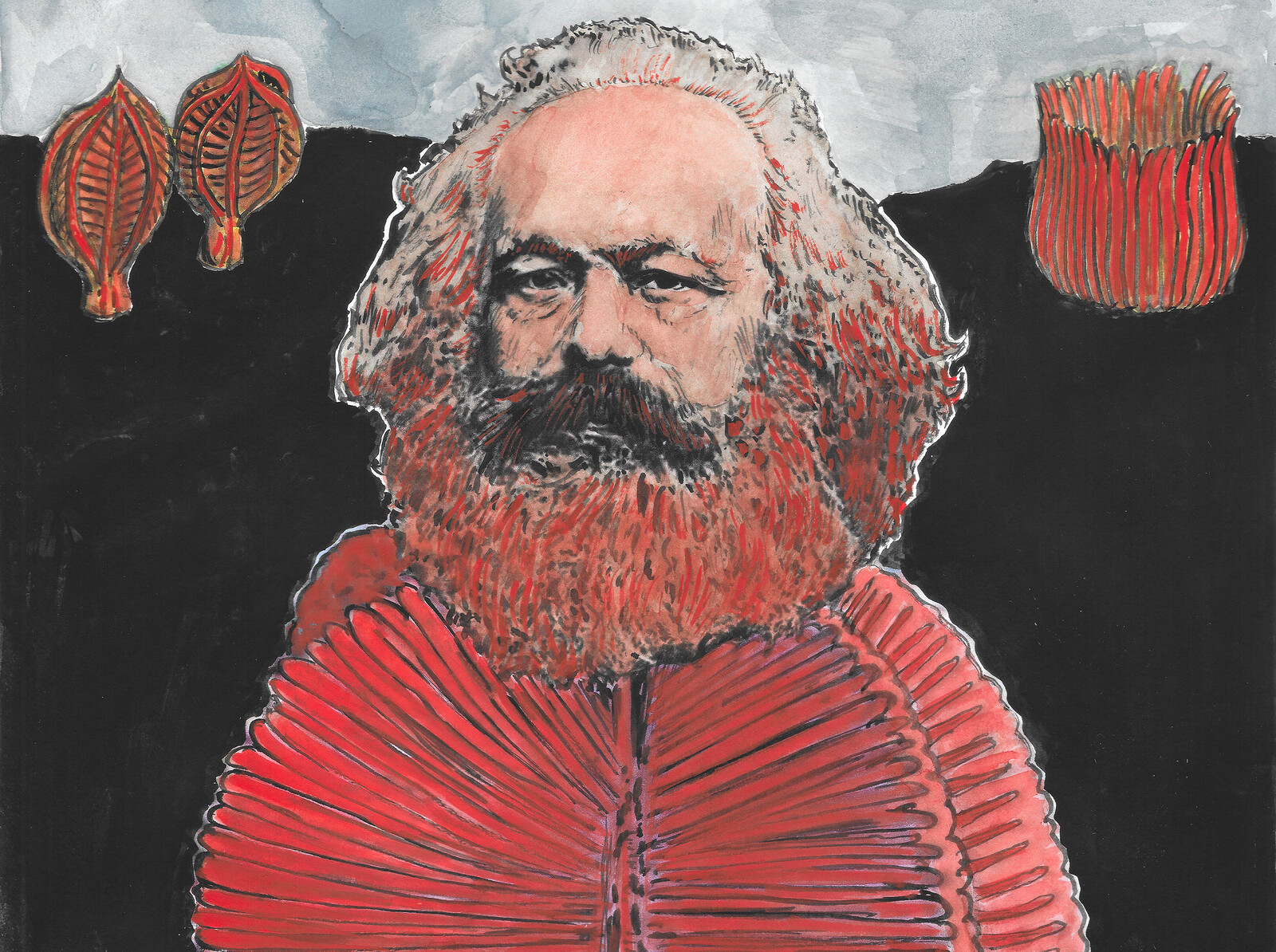

Decades of capitalist propaganda has reduced the notion of collectivization to Stalinist terror. This flattening of the term dismisses the breadth of forms that collectivization can take: from nationalizing communal resources and production, to other-than-human redistribution efforts to establish comradely ecologies. It is therefore essential to explore the collectivized imaginaries and practices—collectivizations, in the plural—that make egalitarian forms of life imaginable and actionable.

For more than a half century, the Yugoslav collective body performed enormous ideological and metabolic work, and became exhausted. Rescued from the dustbin of history, it was turned into an “ur” collective body that neoliberal capitalism and the twenty-first century tore limb from limb—dismembering the collective body. Everyone took a piece—museums, galleries, archives, books. Where that collective body once stood is now an empty stage—which also means that new beginnings are possible. How can we build our collective body anew?

Omuz is a new solidarity network in Turkey that came into existence shortly after the worldwide lockdowns in early spring 2020. A few days after the first Covid case was “officially” announced in Turkey, a small group of art professionals began seeking financial support for art practitioners who lost their secondary jobs, which had been their primary sources of income.

With the industrial revolution, curing and caring for oneself took an individualist turn: it became a private affair for the privileged. Self-care was turned into a sign of cultural sophistication for the Western imperialist class.

We are drawing on ideas that bring people together in conversation rather than force them into authoritative processes. Conversations meander, and decisions spring forth. We reduce individual control and ownership. We share power and authority, as well as respecting silence and absence. Ideas emerge organically without clear intellectual ownership. It is a collage: thousands of pieces of ideas come together. Bad ideas are polished up with a little collective imagination.

Through its aesthetic liberation of things, ideas, and layers of time, art constructs imaginaries of interdependence, which in their own way contribute to a society of solidarity. Today, during this time of pandemic, we like to talk about us all being in the same boat, a metaphor that has replaced the catastrophic image of overcrowded boats of refugees crossing the Mediterranean. But the most powerful metaphor of the present time is the metaphor of the virus, which represents how everything influences everyone. But this is only our view of viruses, our exploitation of its properties. What viruses themselves think about this, nobody knows.

Bennani replaced the singing with canned screams and nothing else. There’s no faint rustle of the crowd, as in the original footage, for example. Nor has she applied any reverb, which would create the effect of the vocalists inhabiting the same acoustic space. All the members of this choir howl in isolation—from the world (there’s no diegetic sound) and from each other (there’s no reverb). A crowd vocalizing with none of the subtle audio cues that let us know we are in a crowd: Bennani’s audio treatments mirror the eerie social alienation that is only possible in digital domains.